Thomas Jackson’s story has been largely untold, but the record he left behind demands historical analysis. His erudite letters have much to contribute to our understanding of the abolitionist movement, the evolution of attitudes to race, and everyday experiences of the U.S. Civil War. Jackson’s status as a British immigrant also provides us with an added analytical layer in which to view American abolition, race, and the Civil War in a transnational context.[1] In this article, I introduce the Thomas Jackson Collection and what we can learn from it.

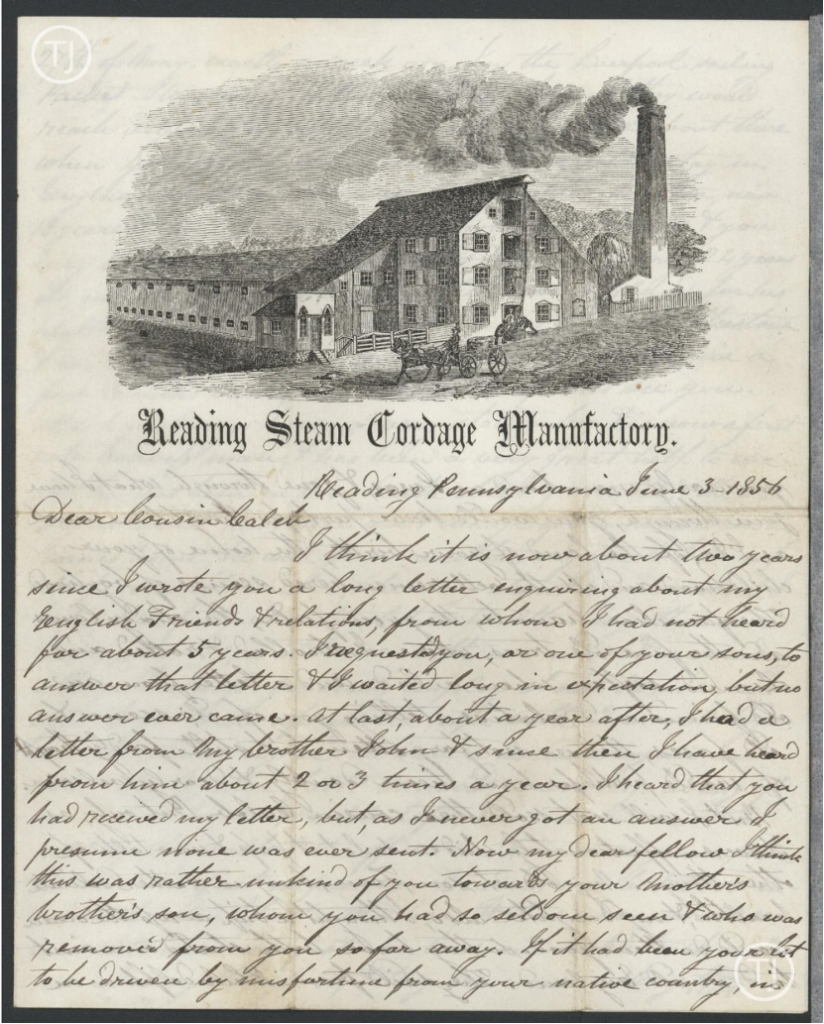

Following in his father’s footsteps, Thomas Jackson, whose life came to be absorbed by the spirited abolitionist movement of his day, became a successful rope-making trader not long after his relocation to America, circa 1829. His father, John Jackson, who “suffered persecution of a year’s imprisonment and three times in the pillory for what he spoke and published in the cause of the revolted colonies,” served as a consistent moral compass for his son.

Born into England’s working class, Thomas Jackson admired the newly christened American Republic.[2] Although he knew, by his own account, next to nothing about slavery in America before he emigrated there, Jackson found his spiritual calling in political activism—abolitionism, in particular.

Jackson’s path to American politics was far from linear. Born on December 7 1805, Thomas grew up in the rural town of Ilkeston, roughly fifty miles northeast of Birmingham. There he was raised, along with six siblings, by working-class parents and likely received no more than a basic education. Despite his modest upbringing, by the time he passed away in Reading, Pennsylvania in 1878, he came to be known more for his impassioned abolitionist work than for the trade he was born into.

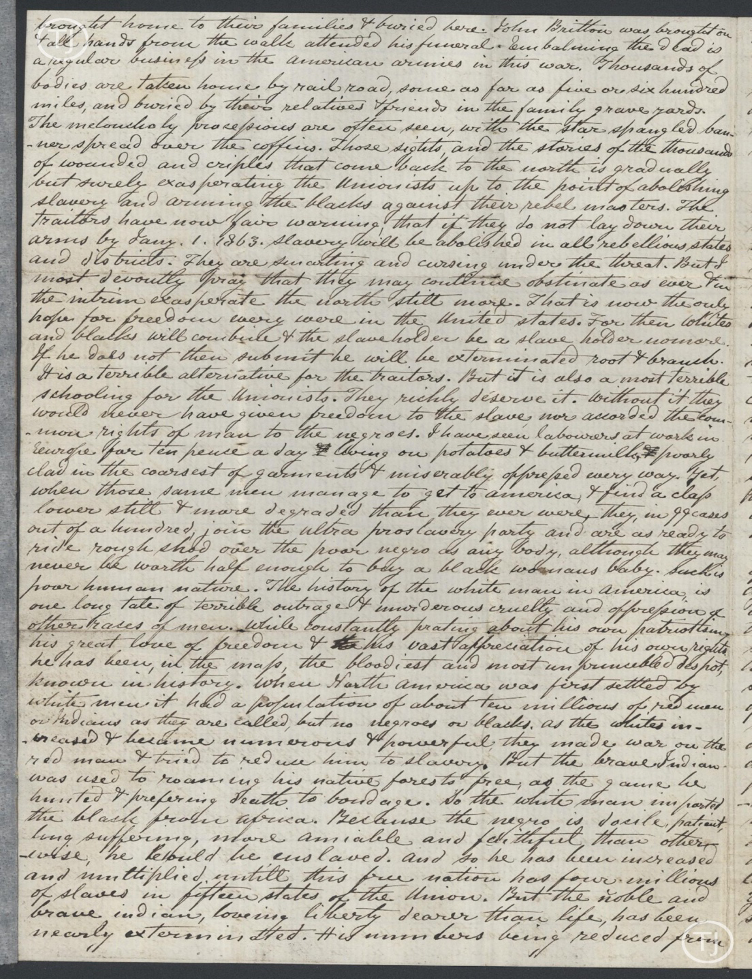

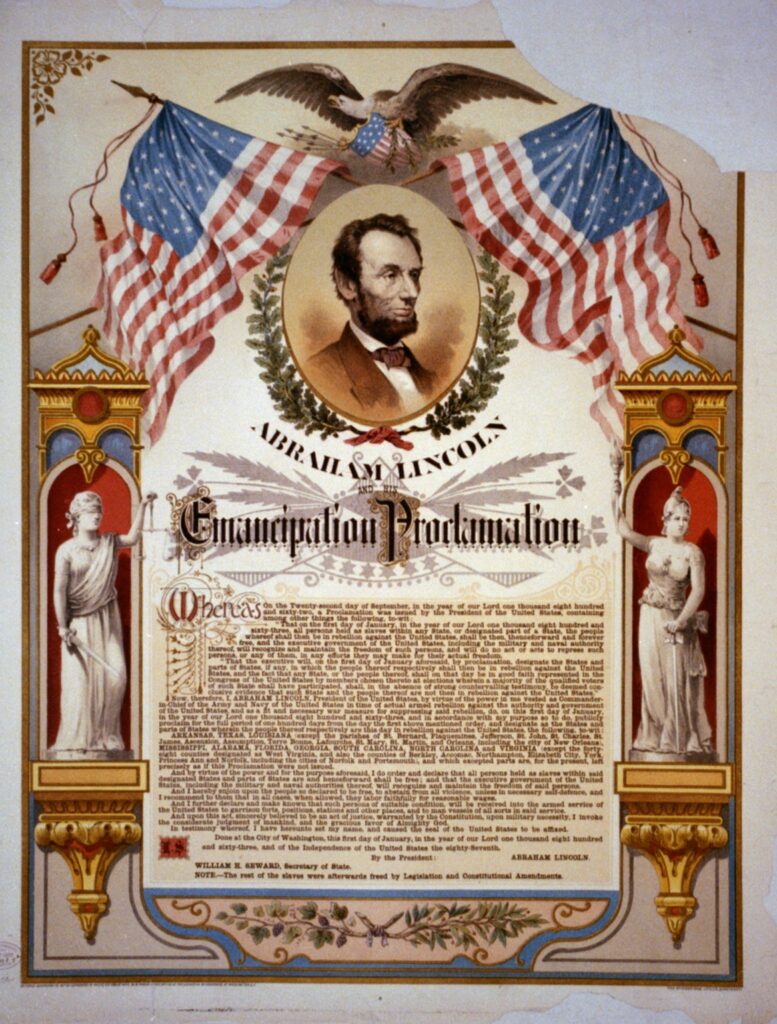

Jackson empathized with the anti-slavery cause after witnessing the stunning inhumanity of an American slave market. Because of this, he supported the Union when the war broke out, hoping that the terrible violence would at least serve a worthy purpose: bringing an end to slavery. In October 1862, with the war grinding on perhaps longer than anticipated, Thomas wrote that “the traitors [i.e. the confederate states] have now [received] fair warning; that if they do not lay down their arms by Jan. 1. 1863. slavery will be abolished in all rebellious states and districts…I most devoutly pray that they may continue obstinate…That is now the only hope for freedom every were [sic] in the United States.”[3]

Judging by his letters alone, it’s clear that Thomas Jackson embraced abolitionism as a core part of his identity. By extension, he considered himself a purist when it came to honoring the “free principles and republican government” for which the United States ostensibly stood.[4]

Because values like individual liberty and freedom of expression transcended national borders, it mattered little to him that he was born in England and, therefore, lived in the United States as an immigrant.

The collection

These strongly-held ideals shine through in almost every letter and newspaper editorial that make up the bulk of the Thomas Jackson Collection. His reports on slavery and the Civil War have been painstakingly transcribed, organized, and curated to offer historians a rare glimpse into a unique abolitionist who was entangled in both American and British politics. While the original letters are now safely housed in the Library of Congress’ Manuscript Division, their digitized copies are fully accessible online thanks to the efforts made by Jackson’s descendant, John Paling, and his team, to organize and digitize the collection.[5]

The Civil War and the nineteenth-century abolitionist movement have of course been studied in depth. Many of these studies take a top-down perspective. Thomas Jackson’s collection of letters provides a valuable and much-needed grassroots perspective. It is rare to find source material written from Jackson’s vantage point, that is letters penned by someone from a working-class background who also understood the value of recording and commenting on the magnitude of his historical moment: America’s mid-nineteenth-century political crisis.

Jackson arrived in the United States in 1829. Still in his twenties, he held an idealized view of the country that would soon be complicated by his encounter with the brutalities of slavery and violent division. Like other immigrants, he primarily sought fresh opportunities that had been closed off to him in his home country. In this case, his father’s political imprisonment drove the family to bankruptcy.[6] As such, Thomas and his brother Edward suffered from meager resources once setting foot on the American continent. Despite the initial challenges, he and his brother managed to secure their footing in Reading, Pennsylvania, by using the local Schuylkill Canal to establish a rope-making business.

“…we are doing a large business. Generally employ about 20 men and eight boys…Annexed is an engraving of our wheel houses, Hackle lofts, and engine house & a part of the walk & the office. We have a very nice place here now and fast improving.”[7]

Despite facing near penury, Thomas Jackson’s entrepreneurial spirit eventually allowed him to rise to a prosperous position, giving him resources very different from those he was born to. His relative financial success enabled him to become a kind of working-class autodidact. His lucid letters, which are notable for the quality of the prose and the artistic flourish of his penmanship, suggest a level of learning that was mainly confined to the privileged elite of the day.

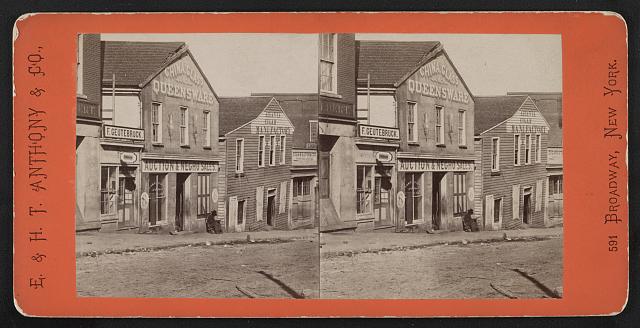

Although he became a successful businessman in America, the country failed to fully live up to his expectations. The young republic, a self-proclaimed land of opportunity and equality, was also home to what he considered a blight on the American experience: the continuation of slavery.

In a letter to his cousin, Caleb Slater, back in England, which was subsequently published in a local newspaper, Jackson claimed to have first witnessed a slave market in 1833. Given the “glowing ideas of free America” his father had instilled in him as a boy, he “never dreamed that such a thing was possible as liberty and slavery existing together under a free government, and just laws.” He was adamant: I “Never thought such a thing could be; do not now think it can be; know now it cannot be.”[8]

From this introduction, Thomas went on to describe the slave auction scene underway in Richmond, Virginia, where a “most interesting young woman…as white as [his] own English wife” stood at the auction block before a “queer-looking crowd [of] dirty mouthed, rum-drinking tobacco chewers…liable to become the property, and entirely subject to the power and the lust of the grossest brute among them, if he bid high enough!”[9]

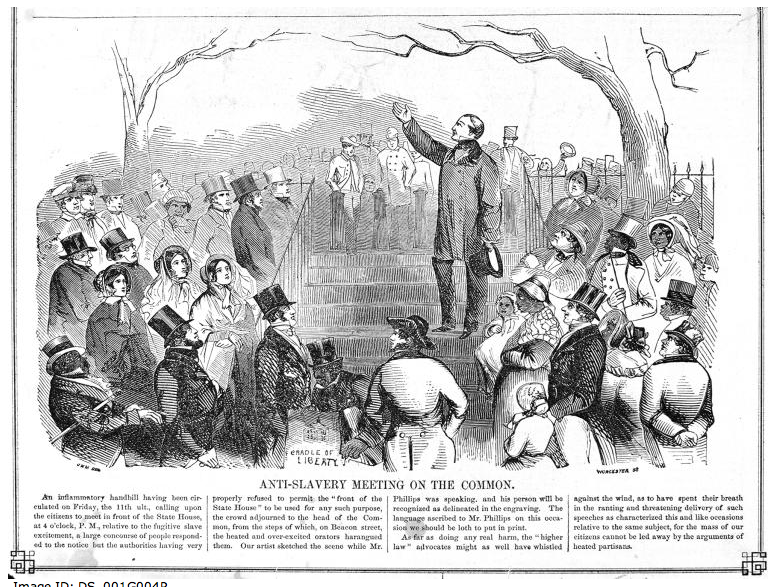

Jackson was enraged by the harsh realities of a slave republic. He used his unique perspective to approach the abolitionist movement with a distinct strategy. He leveraged his connections in England to provide British citizens firsthand reports of slavery in America, as he did with the letter above. In doing so, he hoped his visceral and emotional first-person stories about slavery’s horrors would influence British public opinion. Eventually, he hoped the British government would be discouraged from supporting the American cotton trade, which was intertwined with slavery. When the Civil War came, he doubled down on these efforts, as he became aware that Britain’s “freedom-hating” aristocracy, with the government’s tacit support, secretly aided the “villainous rebels” as a means of keeping the cotton industry alive.[10]

Examining Jackson’s rhetoric and the political positions they reveal enable us to answer questions about the nature of nineteenth-century abolitionism. Were the aims of British abolitionists living in the United States more radical than those of their compatriots living back in England?[11] If so, were the political differences more a matter of class or of vantage point? In other words, did it require witnessing slavery firsthand for an abolitionist to draw a harder line on the issue, or were other factors, such as social standing, more important in delineating the moderates from the radicals?

If we were to view Jackson’s political discourse alongside the writings of the British metropole’s largely elite circle of abolitionists, it’s easy to discern a more fiery, visceral retelling of slavery’s horrors—and of the urgent need to abolish it immediately and by any means necessary.[12] Early in the war, before the 1863 Emancipation Proclamation, Jackson witnessed the country “in all directions…being desolated by fire and sword and shell” and declared that “slavery must perish, with all its abettors.”[13] Perhaps traveling to Harrisburg and seeing firsthand the rebels and Union soldiers make preparations for further carnage enabled him to imagine not a gradual but rather an immediate—and, if necessary, violent—end to the institution of slavery, a “doom it so richly deserves.”[14]

Thomas Jackson’s letters reveal an unwavering commitment to abolition; they also show striking ways in which race underpinned life both in the US and in Britain. There is little doubt as to the value of this source material for scholars studying race, particularly in early America, for Jackson’s writings betray his struggles to come to terms with race and racism in his adopted country.

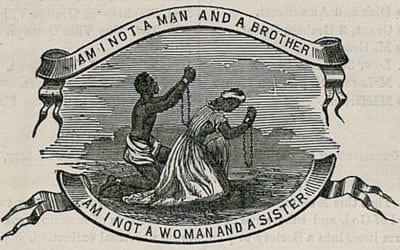

As an abolitionist, Jackson clearly intended to convince readers of the fundamental humanity of Black slaves and the need to guarantee equality to vulnerable non-white groups.[15] But Jackson was also a product of his time and he displayed attitudes rooted in this.

As shown in his account of the slave market above, Jackson obsessed over the surprising “whiteness” of many enslaved people he encountered. He was scandalized to see men and women with complexions similar to his own being held in bondage. Returning to his account of the slave market, we find a long digression into the racial characteristics of both the slaves and their would-be owners:

I suppose I saw 15 or 20 sold, of all shades of colour [sic.] from black to three-quarters white. Then they brought out a good-looking, well-dressed, modest, and most interesting young woman, about 23 or 24 years old, and, to all appearance to me, as white as my own English wife. She had a little daughter about three years old by her side, and a beautiful babe of about a year old in her arms, both, for all I could see, as white as my own children at home…the offspring of slave mothers have been whitening, until the very small taint of negro blood is not perceivable in many.[16]

Jackson went on to describe the men placing bids as “dirty-mouthed” and “seemingly not half as white as their victims,” preparing to subject an example of “feminine loveliness” to their “power and [their] lust.”[17]

To him, the white complexion of many of these Black slaves seemed to underline the patent absurdity and cruelty of slavery, especially when placed against the “brute” status of the southern whites he encountered.

There’s little doubt, too, that Jackson knew evoking whiteness would be effective in garnering sympathy from white readers. In a later letter describing the lecture tours organized by abolitionists, in which runaway slaves featured prominently, he doubled down on this rhetoric. Many of the former slaves, he writes, were “so white that no one would ever suspect that they had a drop of African blood in their veins.”[18] In this way, whiteness became a term loaded with value for Jackson even as he denounced the racism that underpinned slavery.

The work of Mary Niall Mitchell and Martha Cutter, among others, points out that American abolitionists readily employed the language of whiteness as a tool to sway public opinion on the issue.[19] Although he was born in Britain, Thomas Jackson, used a similar rhetorical strategy. He may have arrived at this independently or adopted it from wider writings.

It is worth considering the implications behind an English immigrant’s echoing of American attitudes about race. Given that Jackson largely aimed his writing to English readers, his apparent confidence that an English readership would be equally moved by American racial rhetoric is significant. Indeed, this challenges assumptions about the uniqueness of American racial thought.

None of this is to say that Thomas Jackson ignored enslaved people who could not “pass” for whites. Nor did he mean to suggest that slaves with darker skins were somehow less deserving of sympathy or equality. Further down in his letter concerning former slaves, he mentions he employed darker-skinned freedmen, one of whom was a “smart fellow,” another a “deep thinker,” and another who demonstrated “intellect…of a high order.”[20] Yet when quoting them directly, he transformed his interlocutors into characters out of a minstrel show, capturing their voices with terms like “day” instead of “they” and “den” instead of “then.”[21] In short, his commitment to abolitionism was sometimes contradicted by his racialized language.

Most people don’t know Thomas Jackson but he left behind a remarkable historical record. This provides an opportunity for further reflection on a critical moment in the nation’s history. As such, this collection deserves a broad readership.

The views and opinions expressed in this article or video are those of the individual author(s) or presenter(s) and do not necessarily reflect the policy or views of the editors at Not Even Past, the UT Department of History, the University of Texas at Austin, or the UT System Board of Regents. Not Even Past is an online public history magazine rather than a peer-reviewed academic journal. While we make efforts to ensure that factual information in articles was obtained from reliable sources, Not Even Past is not responsible for any errors or omissions.

[1] For representative scholarship, see Mason, Matthew. “The Battle of the Slaveholding Liberators: Great Britain, the United States, and Slavery in the Early Nineteenth Century.” The William and Mary Quarterly 59, no. 3 (2002): 665–96. https://doi.org/10.2307/3491468.

[2] “Article_1859-03-01 – Thomas Jackson Letters.” 2023. Thomas Jackson Letters. July 28, 2023. https://thomasjacksonletters.com/articles/article_1859-03-01/.

[3] “TJ_Letter_1862-08-12 – Thomas Jackson Letters.” 2023. Thomas Jackson Letters. August 25, 2023. https://thomasjacksonletters.com/letters/letter_1862-08-12/.

[4] “Article_1844-10-26 – Thomas Jackson Letters.” 2023. Thomas Jackson Letters. July 28, 2023. https://thomasjacksonletters.com/articles/article_1844-10-26/.

[6] “Article_1825-12-24 Bankruptcy – Thomas Jackson Letters.” 2023. Thomas Jackson Letters. March 25, 2023. https://thomasjacksonletters.com/other-documents/np_1825-12-24-from-london-gazette/.

[7] Thomas Jackson in letter to cousin Caleb Slater, June 3, 1856. “TJ_Letter_1856-06-03 – Thomas Jackson Letters.” 2023. Thomas Jackson Letters. March 22, 2023. https://thomasjacksonletters.com/letters/letter_1856-06-03/.

[8] “A Native of Ilkeston in an American Slave Market.” Thomas Jackson Letters. August 25, 2023. https://thomasjacksonletters.com/letters/letter_1862-08-12/. Published in Eastwood, England area newspaper September 11, 1862.

[9] Ibid.

[10] “TJ_Letter_1864-09-01 – Thomas Jackson Letters.” 2023. Thomas Jackson Letters. March 22, 2023. https://thomasjacksonletters.com/letters/letter_1864-09-00/.

[11] For British abolitionism, see Huzzey, Richard. “The Slave Trade and Victorian ‘Humanity.’” Victorian Review 40, no. 1 (2014): 43–47. http://www.jstor.org/stable/24497035.

[12] For comparative analysis of British and American abolitionism, see Mason, Matthew. “The Battle of the Slaveholding Liberators: Great Britain, the United States, and Slavery in the Early Nineteenth Century.” The William and Mary Quarterly 59, no. 3 (2002): 665–96. https://doi.org/10.2307/3491468, and Mason, Matthew. “Keeping up Appearances: The International Politics of Slave Trade Abolition in the Nineteenth-Century Atlantic World.” The William and Mary Quarterly 66, no. 4 (2009): 809–32. http://www.jstor.org/stable/40467542.

[13] “———.” 2023d. Thomas Jackson Letters. August 25, 2023. https://thomasjacksonletters.com/letters/letter_1862-08-12/.

[14]“TJ_Letter_1863-08-20 – Thomas Jackson Letters.” 2023. Thomas Jackson Letters. March 22, 2023. https://thomasjacksonletters.com/letters/letter_1863-08-20/. In addition to political commentary, this letter provides detailed description of Confederate movements at this time which would also prove useful to military historians of the Civil War.

[15] Since Thomas Jackson expressed disapproval of universal voting rights, we should interpret his understanding of equality to be of a limited nature, i.e., the guarantee of “natural rights” for all. For his criticisms on full democracy, see for instance: “TJ_Letter_1862-10-12 – Thomas Jackson Letters.” 2023. Thomas Jackson Letters. March 22, 2023. https://thomasjacksonletters.com/letters/letter_1862-10-12/.

[16] “———.” 2023e. Thomas Jackson Letters. August 25, 2023. https://thomasjacksonletters.com/letters/letter_1862-08-12/.

[17] Ibid.

[18] “TJ_Letter_1864-04-18 – Thomas Jackson Letters.” 2024. Thomas Jackson Letters. March 27, 2024. https://thomasjacksonletters.com/letters/letter_1864-04-18/.

[19] Cutter, Martha J. “‘As White as Most White Women’: Racial Passing in Advertisements for Runaway Slaves and the Origins of a Multivalent Term.” American Studies 54, no. 4 (2016): 73–97. http://www.jstor.org/stable/44982355. Mitchell, Mary Niall. “‘Rosebloom and Pure White,’ or so It Seemed.” American Quarterly 54, no. 3 (2002): 369–410. http://www.jstor.org/stable/30042226.

[20] “———.” 2024b. Thomas Jackson Letters. March 27, 2024. https://thomasjacksonletters.com/letters/letter_1864-04-18/.

[21] Ibid.