In one of the final scenes of Jeymes Samuel’s gripping 2021 Black Western The Harder They Fall, androgynous outlaw Cuffee (played by Danielle Deadwyler) says a teary goodbye to her comrade “Stagecoach” Mary Fields (Zazie Beetz). The two share a long, not-quite-chaste kiss goodbye as Nat Love, Mary’s main romantic interest in the film, shifts uncomfortably in his saddle. Mary responds with a coy “What you looking at?” before mounting her horse a final time and literally riding off into the sunset with Love, leaving Cuffee behind.

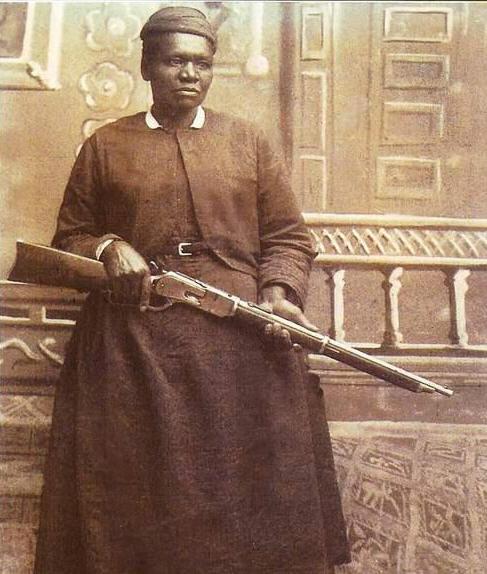

The film, which follows Nat Love and his gang of outlaws on an epic revenge quest across the American southwest, encompasses a litany of historical elisions and inaccuracies, culminating in this moment between Mary and Cuffee. It cements the movie’s final and most glaring lapse: while The Harder They Fall’s vision of the Old West is brazen, bold, and Black, its queer notes amount to little more than whispers. Not only was the real “Stagecoach” Mary Fields (as several writers have noted) much taller, darker, and heavier than she is depicted in the film, she was probably much queerer as well.[i]

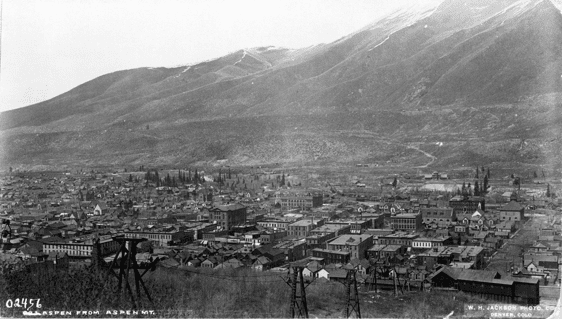

Born in captivity around 1832, Mary Fields spent the early part of her life enslaved by Judge Edmund Dunne of Tennessee. During this time, she reportedly grew very close to Dunne’s sister Sarah, who later became a nun and went by the name Mother Amadeus. After being freed at the end of the Civil War, Fields worked a series of odd jobs before eventually relocating to Toledo to rejoin Mother Amadeus at the Convent of the Sacred Heart, where she worked as a groundskeeper. When Mother Amadeus moved to the Montana Territory in the early 1880s to establish a mission and a small “Indian School,” Fields followed soon after, braving a harsh Montana winter in order to nurse Amadeus through a life-threatening case of pneumonia.

This decision, which one biographer describes as “an act of love,” indicated that the two women’s relationship likely represented something deeper and more complicated than a childhood friendship.[ii] Mary remained at the mission long after Mother Amadeus had recovered from her illness, transporting supplies to the nuns and even personally building Amadeus a hennery, all the while refusing to accept pay for her work. After getting into a shoot-out with a fellow employee who objected to taking orders from a Black woman, Mary was expelled from the mission in 1894, nearly a decade after her arrival. The incident prompted the mission’s male leadership, who already disapproved of Fields’ hard-drinking, “gun-toting”[iii] ways, to directly order Mother Amadeus to send Mary away. Instead, Amadeus helped Fields set up a business – a short-lived restaurant that is mentioned briefly in The Harder They Fall – in the nearby town of Cascade. Later, Amadeus helped Fields secure a star route contract, a position that propelled Mary to fame as the first Black woman mail carrier in the United States.[iv]

For all their closeness, however, the two women’s relationship existed in a social and racial context no amount of loyalty or affection could negate. In tying Mary’s potential queerness to another Black woman (Cuffee) rather than the sister of the man who enslaved her, The Harder They Fall offers a glimpse of Black queerness uncomplicated by these same questions of power. Unfortunately, though, it is only a glimpse. The charged moment between Mary and Cuffee, a character based on Cathay Williams, who famously disguised herself as a man to enlist in the U.S. Army, passes as quickly as it begins, a loose end to be tied up before Mary can have her happy ending with Nat.[v]

Though The Harder They Fall’s director Jeymes Samuel has stressed that the film is not an attempt at historical accuracy so much as a way to honor the often-forgotten story of the Black West,[vi] it is telling that this is the version of that story that ultimately made it to the screen. To depict a woman who in life was never once romantically linked with a man as the ingenue to Nat Love’s swaggering anti-hero was a choice. How much richer could this reimagining have been if different choices had been made—if queerness existed as more than a hint, a shared look, or a fleeting scene of unrealized potential? Samuel’s deeply compelling, cinematically stunning take on the classic Western works in large part because it treats Blackness as something complex and unambiguous. What if it treated queerness the same way?

Candice Lyons is a Ph.D. candidate in The University of Texas at Austin’s Department of African and African Diaspora Studies and a 2021-2022 Black Studies Dissertation Scholar at the University of California, Santa Barbara. Her recent pieces “A (Queer) Rebel Wife in Texas” (2020) and “Rage and Resistance at Ashbel Smith’s Evergreen Plantation” (2020) can be found on Not Even Past. Lyons’ writing can also be found in the 2021 E3W Review of Books, for which she served as special section editor. Her 2021 Feminist Studies article “Behind the Scenes: Elizabeth Keckley, Slave Narratives, and the Queer Complexities of Space” is the winner of the 2020 FS Graduate Student Award.

[i] Ineye Komonibo, “Colorism Clouds The Rich Imagination Of The Harder They Fall,” Refinery 29, November 5, 2021, https://www.refinery29.com/en-us/2021/11/10701439/netflix-the-harder-they-fall-stagecoach-mary-casting-controversy.

[ii] Miantae Metcalf McConnell, “Mary Fields’ Road to Freedom,” Black Cowboys in the American West: On the Range, on the Stage, Behind the Badge, edited by Bruce A. Glasrud, Michael N. Searles, and Albert S. Broussard (Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 2016).

[iii] Gary Cooper, “Stagecoach Mary: A Gun-Toting Black Woman Delivered the U.S. Mail in Montana,” Ebony (1977).

[iv] McConnell, “Mary Fields’ Road to Freedom.”

[v] DeAnne Blanton, “Cathay Williams: Black Woman Soldier 1866-1868,” Buffalo Soldier, Originally Published 1992, https://www.buffalosoldier.net/CathayWilliamsFemaleBuffaloSoldierWithDocuments.htm.

[vi] Andrew R. Chow, “The Real Black Cowboys That Inspired Netflix’s The Harder They Fall,” Time, November 3, 2021, https://time.com/6111612/the-harder-they-fall-true-story/.

The views and opinions expressed in this article or video are those of the individual author(s) or presenter(s) and do not necessarily reflect the policy or views of the editors at Not Even Past, the UT Department of History, the University of Texas at Austin, or the UT System Board of Regents. Not Even Past is an online public history magazine rather than a peer-reviewed academic journal. While we make efforts to ensure that factual information in articles was obtained from reliable sources, Not Even Past is not responsible for any errors or omissions.