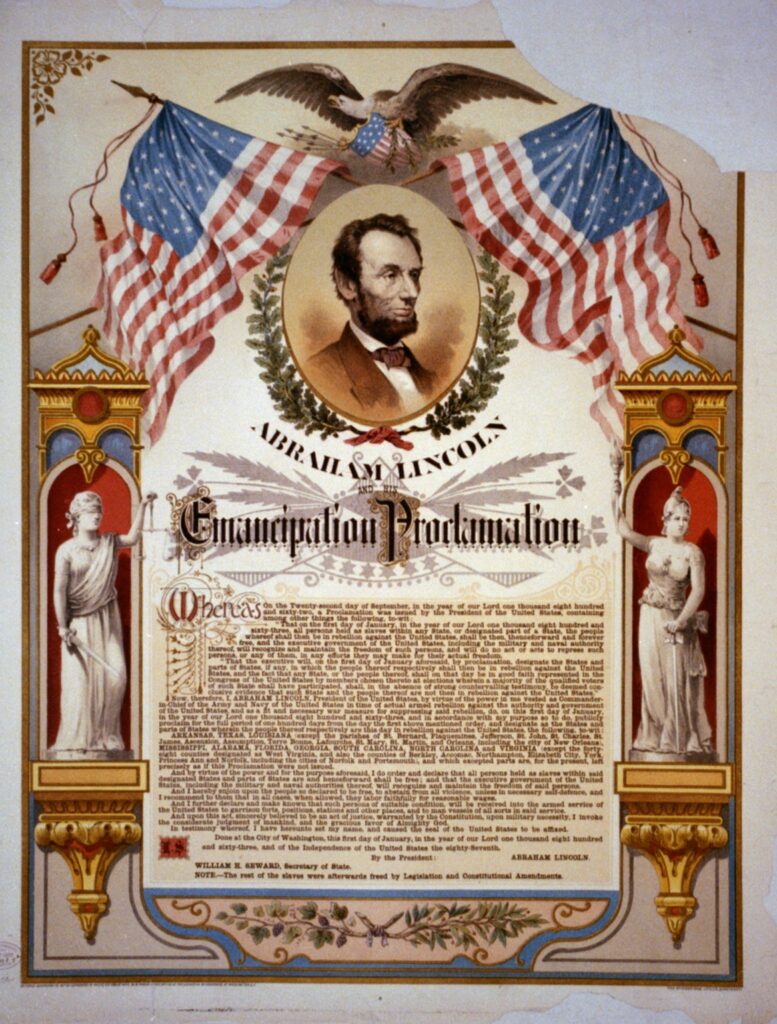

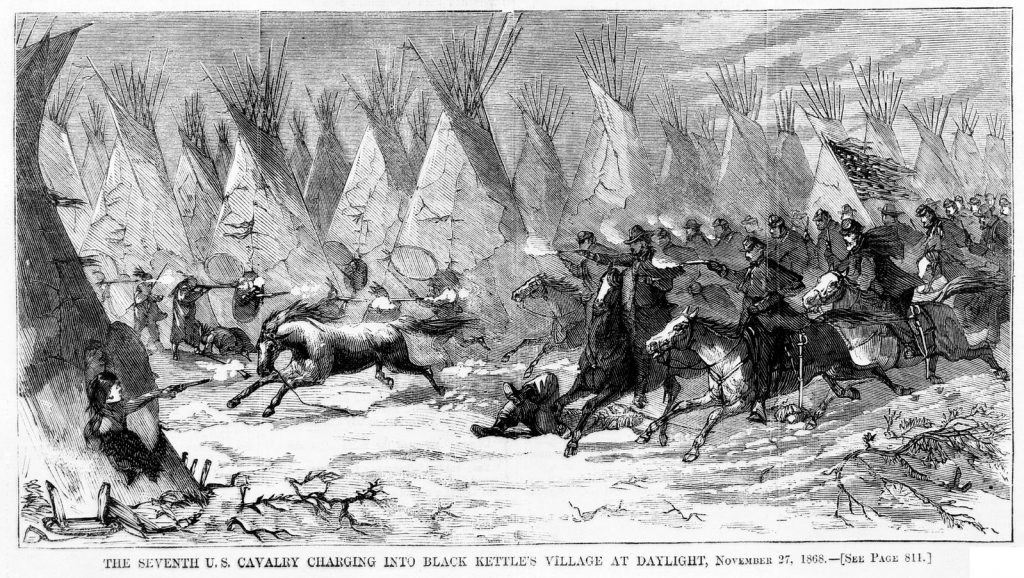

Jeremi and Zachary sit down with Jeffrey Toobin to discuss the critical relationship between the U.S. judiciary, particularly the Supreme Court, and the executive branch. Discussion centers around the contentious and politically charged topic of presidential pardoning power. The episode covers historical instances, such as Lincoln’s and Johnson’s post-Civil War pardons, Gerald Ford’s pardon of Nixon, and more recent uses of the pardon power by Presidents Trump and Biden.

Zachary sets the scene with his poem, “It is a miracle the Earth can twist.”

Jeffrey Toobin is the chief legal analyst for CNN and a contributing opinion writer for the New York Times. He is the author of numerous books, including: The Oath: The Obama White House and the Supreme Court and Homegrown: Timothy McVeigh and the Rise of Right-Wing Extremism. His most recent book is: The Pardon: The Politics of Presidential Mercy.