During the summer of 2016, we will be bringing together our previously published articles, book reviews, and podcasts on key themes and periods in the history of the USA. Each grouping is designed to correspond to the core areas of the US History Survey Courses taken by undergraduate students at the University of Texas at Austin.

Starting Points:

We start with Marc William-Palen’s discussion of the Causes of the Civil War.

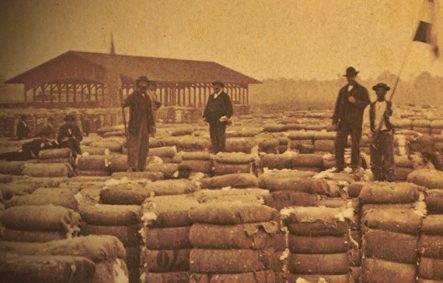

Next, we delve into a more detailed case study as Jacqueline Jones explores the Civil War in Savannah.

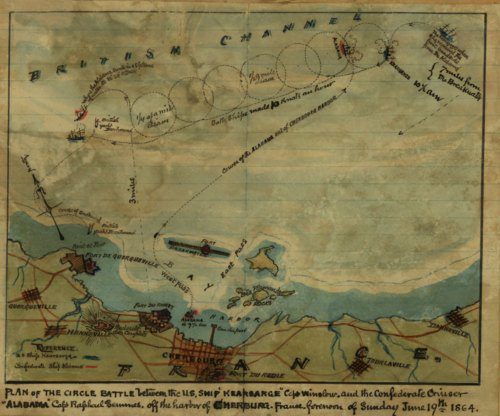

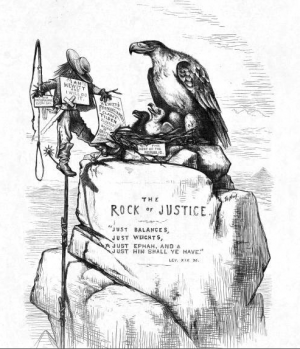

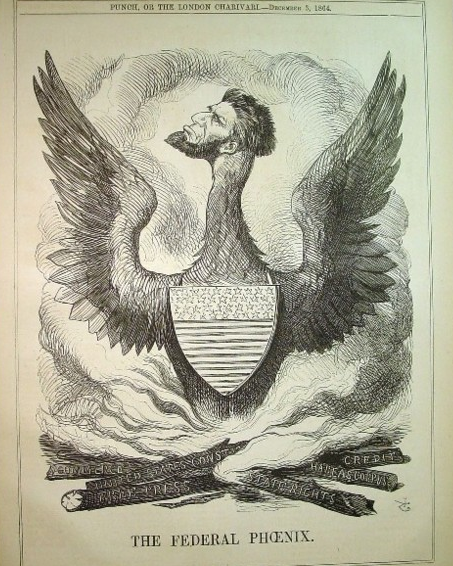

Charley Binkow explore’s George Mason University’s Virginia Civil War Archive, highlighting the portrayal of the Civil War in Harper’s Weekly, one of the authoritative voices in news, both in the North and the South.

And on 15 Minute History we have: Causes of the U.S. Civil War part 1 and part 2:

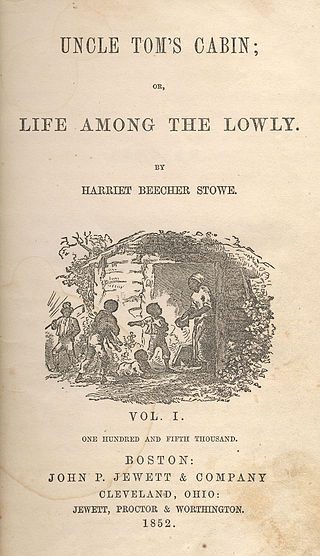

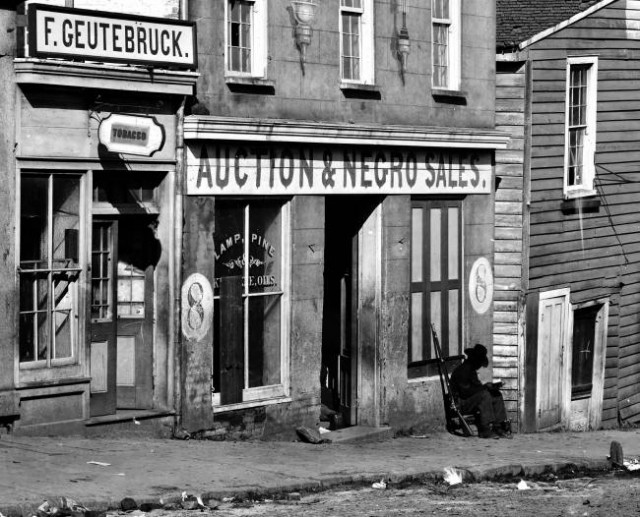

In the century and a half since the war’s end, historians, politicians, and laypeople have debated the causes of the U.S. Civil War: what truly led the Union to break up and turn on itself? And, even though it seems like the obvious answer, does a struggle over the future of slavery really explain why the south seceded, and why a protracted military struggle followed? Can any one explanation do so satisfactorily?

In the century and a half since the war’s end, historians, politicians, and laypeople have debated the causes of the U.S. Civil War: what truly led the Union to break up and turn on itself? And, even though it seems like the obvious answer, does a struggle over the future of slavery really explain why the south seceded, and why a protracted military struggle followed? Can any one explanation do so satisfactorily?

Historian George B Forgie has been researching this question for years. In this two-part podcast, he’ll walk us through five common–and yet unsatisfying–explanations for the most traumatic event in American history.

Recommended Books and Films on the Civil War:

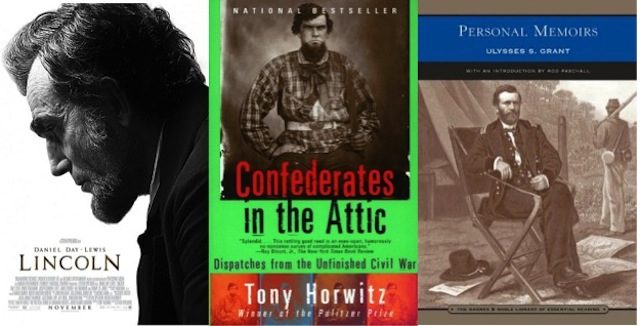

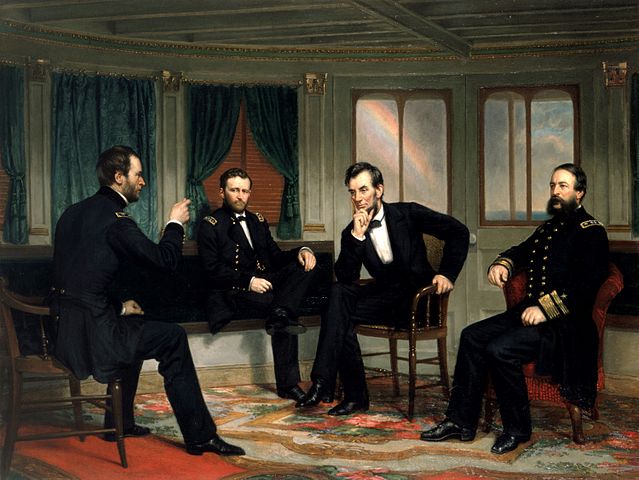

Mark Battjes discusses Ulysses S. Grant’s Personal Memoirs (Barnes and Noble, 2003)

And, H. W. Brands recommends more reading on Ulysses S. Grant: memoirs, biographies, histories.

Nicholas Roland offers historical perspectives on Spielberg’s Lincoln (2012).

Kristie Flannery reviews Confederates in the Attic: Dispatches from the Unfinished Civil War, by Tony Horwitz (Pantheon, 1999)

Finally, George Forgie recommends seven Civil War Classics.

Texas & The Civil War:

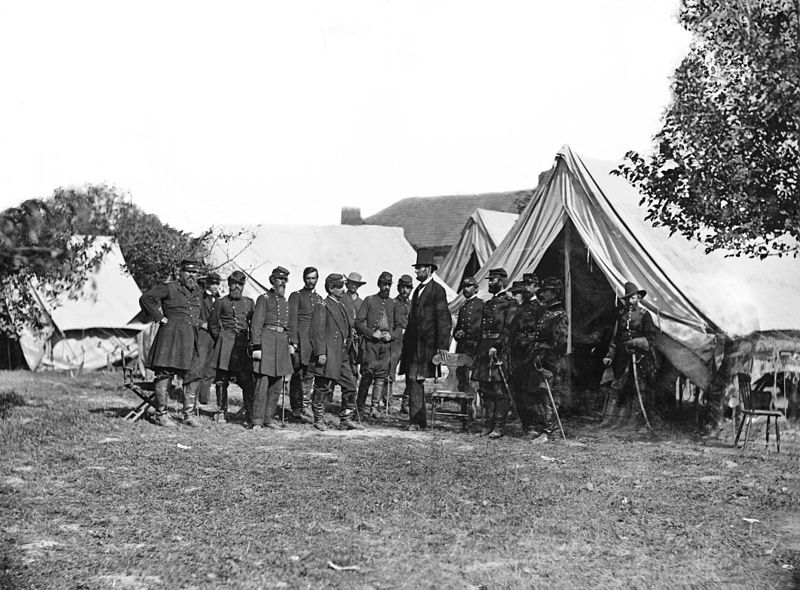

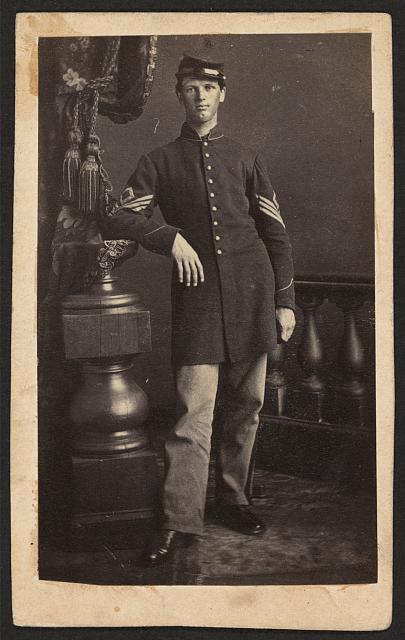

Nicholas Roland explores the experiences of Texans fighting in the battle of Antietam.

Nakia Parker follows the fascinating experiences of the Texans who moved to Brazil after the defeat of the Confederacy.

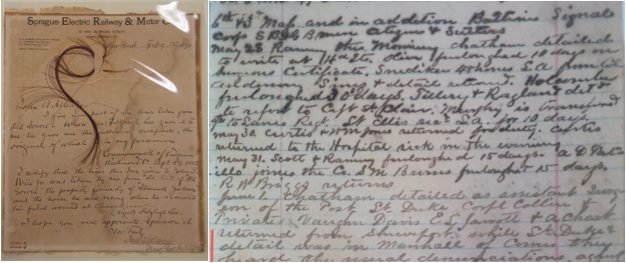

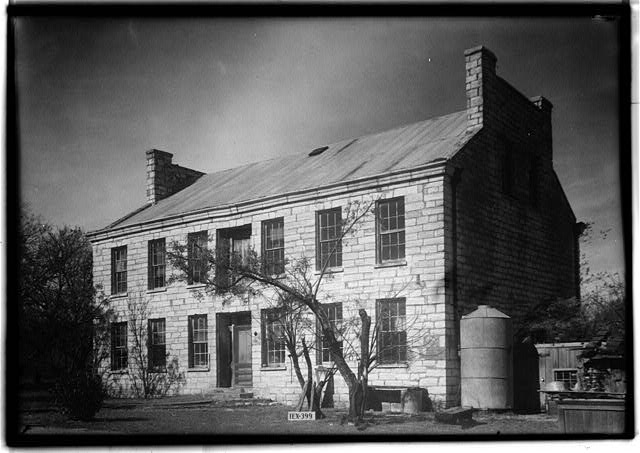

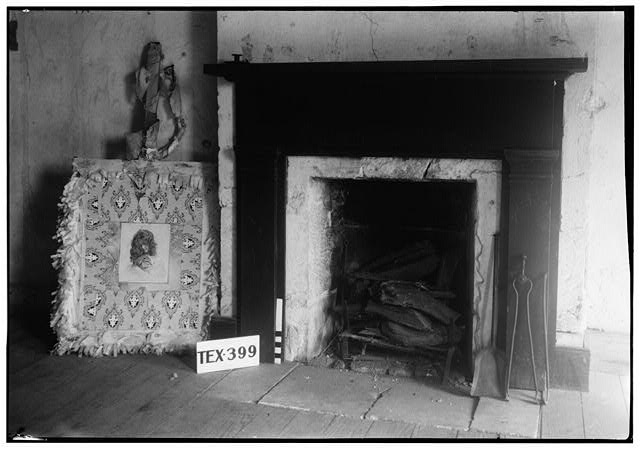

Two graduate students discuss intriguing Civil War sources found in the Dolph Briscoe Center for American History, University of Texas at Austin:

The Legacy of the Civil War:

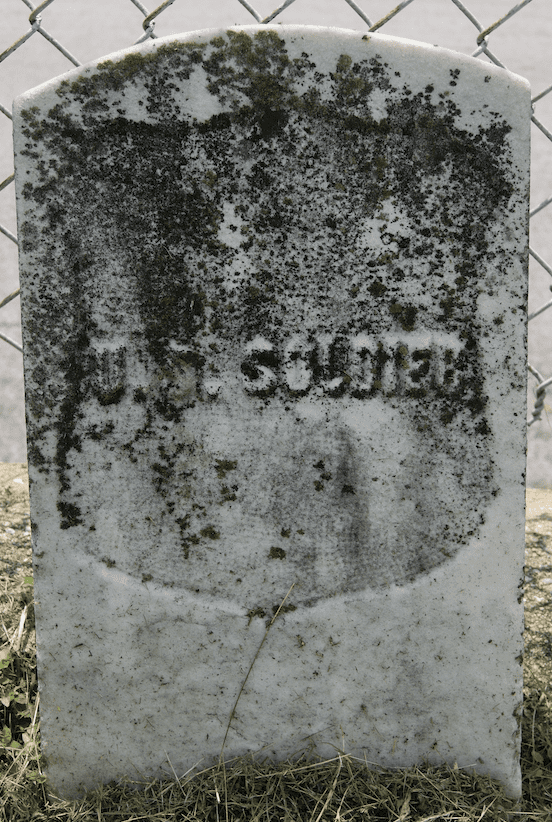

Nicholas Roland remembers the Unknown Soldiers of the post-Civil War period buried in Austin’s Oakwood Cemetery and the story of Milton Holland, a mixed race native of Texas who was awarded the Medal of Honor for his actions during the Civil War battle of Chaffin’s Farm.

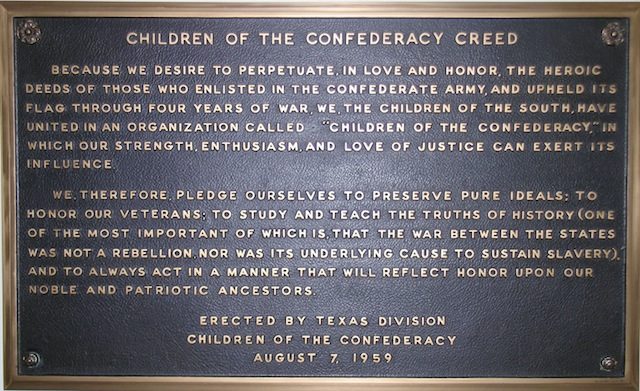

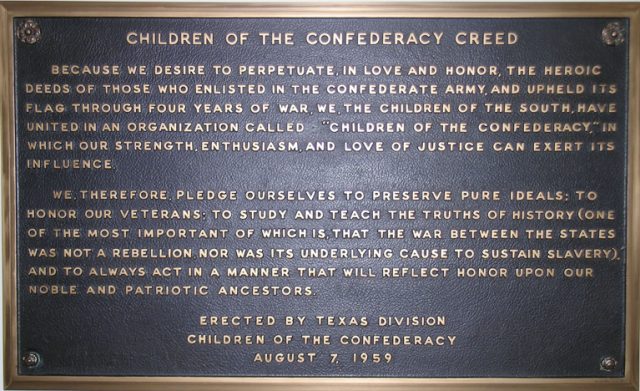

And finally, our editor Joan Neuberger compiled some recommended readings on On Flags, Monuments, and Historical Myths

by Adrienne Morea

by Adrienne Morea

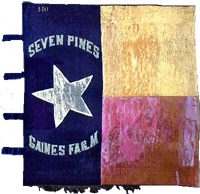

The “Ragged Old First” lost their regimental colors as well. Historian

The “Ragged Old First” lost their regimental colors as well. Historian