In this accessible and remarkably balanced synthesis, Melvyn Leffler, one of the most distinguished and prominent historians of American foreign relations, offers a refreshing interpretation of Cold War policymaking from the vantage points of both Washington and Moscow.  Rejecting the oft-repeated assertion that U.S. foreign policymakers were ignorant or inattentive to the realities of power in the Soviet Union and the complexities of Third World nationalism, Leffler argues that cold warriors on both sides of the iron curtain were in fact keenly aware of the liabilities inherent in the zero-sum approach to international politics. Benefiting from access to multiple archives and a clear command of the secondary historical literature, Leffler has crafted a persuasive and thoroughly documented analysis that recasts the Cold War as not simply a political, economic, or military confrontation, but a battle “for the soul of mankind.” In doing so, he has transcended the scholarly debate over whether economic, structural, or ideological factors were more influential in determining the course of Cold War history.

Rejecting the oft-repeated assertion that U.S. foreign policymakers were ignorant or inattentive to the realities of power in the Soviet Union and the complexities of Third World nationalism, Leffler argues that cold warriors on both sides of the iron curtain were in fact keenly aware of the liabilities inherent in the zero-sum approach to international politics. Benefiting from access to multiple archives and a clear command of the secondary historical literature, Leffler has crafted a persuasive and thoroughly documented analysis that recasts the Cold War as not simply a political, economic, or military confrontation, but a battle “for the soul of mankind.” In doing so, he has transcended the scholarly debate over whether economic, structural, or ideological factors were more influential in determining the course of Cold War history.

Rather than adopting a standard narrative approach, Leffler focuses on both American and Soviet political leadership during five distinct intervals of potential détente—Truman and Stalin and the origins of the Cold War; Eisenhower and Malenkov during the power struggle within the Kremlin in the wake of Stalin’s death; Khrushchev, Kennedy, and LBJ in the aftermath of the Cuban missile crisis; Carter and Brezhnev and the erosion of détente; and finally, Gorbachev, Reagan, and Bush, and the end of the Cold War. Leffler argues that, while the decisions of policymakers were clearly shaped by perceptions of both threat and opportunity, the constraints of the international system within which they operated also severely circumscribed their freedom of action.

U.S. President Harry Truman and Soviet Premier Joseph Stalin alongside their advisors at the Potsdam Conference, July 18, 1945. Image via Wikimedia Commons.

This raises a conceptual problem with Leffler’s analysis, however. Although emphasizing contingency as a major factor in the arc of history, Leffler argues that Cold War leaders were trapped within ideological prisons of their own making, suggesting perhaps that the trajectory of the Cold War was more predetermined than he allows for. And viewing the time periods he has chosen for analysis here as moments of missed opportunity, he proceeds to prove that American and Soviet policymakers were so limited in their options that they had little choice other than to behave as they did. If that is in fact the case, the reader is left wondering whether there truly were opportunities for peace during these critical junctures.

These criticisms should not, however, obscure the fact that Leffler has written one of the most eloquent, balanced, and extensively researched books on the Cold War. “For the Soul of Mankind” certainly raises the bar for scholars of the Cold War, and in its nuanced complexity, elevates the scholarly debate over which factors were more salient in the development of Cold War policymaking. Although not definitive (and what monograph on such a huge topic possibly could be?), “For the Soul of Mankind” will likely grace both undergraduate and graduate level required reading lists for years to come.

A few years ago, after discussing the origins and consequences of the

A few years ago, after discussing the origins and consequences of the

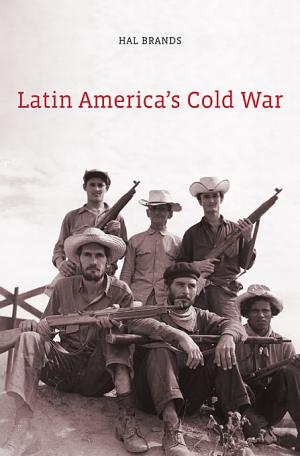

Based on prodigious research in a dizzying array of U.S., Latin American, and even East German archives, Brands’s work advances a trenchant interpretation that cannot be ignored. He argues that the origins of the chaos and instability that ravaged Latin America during the Cold War owed less to U.S. interventionism than to the prevailing confluence of local, regional, and global dynamics.

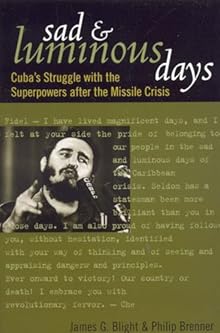

Based on prodigious research in a dizzying array of U.S., Latin American, and even East German archives, Brands’s work advances a trenchant interpretation that cannot be ignored. He argues that the origins of the chaos and instability that ravaged Latin America during the Cold War owed less to U.S. interventionism than to the prevailing confluence of local, regional, and global dynamics. the extent to which the Cuban missile crisis increased U.S.-Soviet cooperation and discr

the extent to which the Cuban missile crisis increased U.S.-Soviet cooperation and discr first successful Marxist revolution just ninety miles away from U.S. shores. Driven by a sense of Third World, post-colonial comradery, Cuban guerrillas staged socialist interventions in Africa in the name of Marxism and anti-imperialism. This book’s depiction of their successes and failures, coupled with Soviet and American reactions to such brazen undertakings, makes for a refreshing literary adventure in Cold War international history.

first successful Marxist revolution just ninety miles away from U.S. shores. Driven by a sense of Third World, post-colonial comradery, Cuban guerrillas staged socialist interventions in Africa in the name of Marxism and anti-imperialism. This book’s depiction of their successes and failures, coupled with Soviet and American reactions to such brazen undertakings, makes for a refreshing literary adventure in Cold War international history.