In January 1968, Alexander Dubček became the First Secretary of the Communist Party of Czechoslovakia, replacing the unpopular communist hardliner Antonín Novotný. The following months of 1968, known as the Prague Spring, brought Czechoslovakia to the attention of the international community. Dubček’s goal was to create “socialism with a human face” through a series of liberalizing reforms, including loosening restrictions on freedom of expression. The Soviet Union attempted to use negotiations to reign in the program which had begun to expand beyond Dubček´s control as 1968 continued, but those efforts were unsuccessful. Under Soviet leadership, the Warsaw Pact invaded Czechoslovakia on August 21, ending the period of reform and its increased freedom of speech. In the wake of the Warsaw Pact invasion, the reform programs were gradually repealed and Dubček was removed as First Secretary in April 1969. The media faced a reimposed regime of Moscow-approved censorship, which would be extended to full censorship in March and April, 1969. The only reform that would survive the rollbacks was the federalization of Czechoslovakia into the Czech Socialist Republic and the Slovak Socialist Republic.

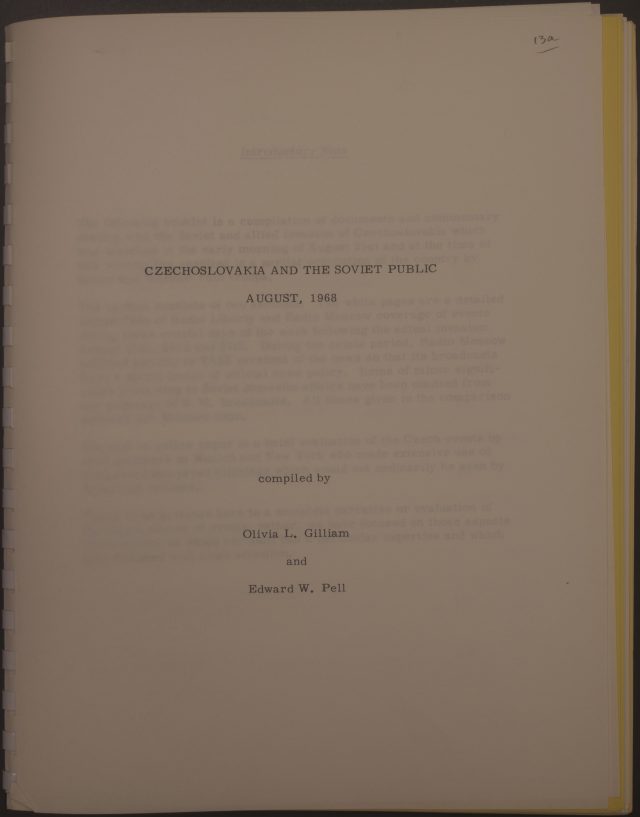

Cover of the March, 1969 edition of Czechoslovak Life. Source: glossycommunism

The magazine Czechoslovak Life was published in Prague throughout this time, and it was distributed in English to an international audience. There is a sharp contrast between the Czechoslovak Life of pre-Prague Spring and the one that emerged in the wake of the crushed uprising. The magazine pre-Spring was much less polished, structured, and organized. Much of the content was dedicated to Czech identity and cultural achievements. In contrast, the magazine of the 1970s featured more highly polished images and articles that discussed the economic progress and welfare of the Czechoslovak state. The strict censorship imposed in 1969 is especially visible in a sudden shift in the language used to describe the Spring. Articles from the immediate wake of the Warsaw Pact invasion but before censorship stress that although the movement was crushed, the liberalizing goals of the Prague Spring were noble attempts to reform the organization of the state in line with the socialist project. After censorship was imposed, the official party narrative of the Prague Spring as a failed right-wing, bourgeoise coup replaced the previous narrative extended to Western audiences in Czechoslovak Life about what the reforms had meant.

The pre-Spring editions of Czechoslovak Life also included an editorial section alongside the table of contents that always starts with “Dear Readers….” The “Dear Readers” column was signed “Editorial Board,” and frequently commented on major international events or the state of the magazine itself. The editorial team on the magazine was largely comprised of the same group of people throughout the period when “Dear Readers” appeared. These people were replaced when “Dear Readers” stopped appearing in the magazine in 1970, therefore it can be assumed that the column was a project of this group of editors. Frantisek Lebenhart and Lenka Reinerová in particular, both Czech-born Holocaust survivors, appear in the list of editors in various positions from 1964 to 1969. The most common political statements made in the “Dear Reader” section were criticisms of then-ongoing imperialist projects by Western powers. In the November 1967 edition, for example, the editors condemned Israel as the aggressor in the Six-Day War and declared that “the editors of this magazine stand alongside the Arab states” in their resistance to colonialism. Throughout the 1960s, the editorial board was also highly critical of American military action in Vietnam.

During Prague Spring, the magazine continued to comment on global imperialism, but also shifted to address the international interest in developments within Czechoslovakia. One article alongside the “Dear Reader” column addresseed a question sent in from a Finnish reader who asks how liberal reforms can happen within a communist system. The editorial board replied that there is nothing inherently problematic with liberalizing reforms in order to advance a more democratic socialist project. The editors of Czechoslovak Life explicitly promoted Dubček´s reforms through the “Dear Reader” column and continued to do so even after the Spring began to be reversed in late 1968 and early 1969. The cover of the January 1969 edition features a photograph of a healthy, adorable child waving a Czechoslovak flag, and the first article on the next page is a telling “Dear Reader” section. This edition asks the reader to carefully verify everything they hear about Czechoslovakia in the coming months, and to remember what their elected leader Alexander Dubček had said. In retrospect, this can be seen as a forewarning of the oncoming censorship that lasted for the next two decades.

1969 was the last gasp of the “Dear Reader” section of Czechoslovak Life. In 1970, the entire editorial board was replaced by names not found anywhere in the editions from the 1960s. Frantisek Lebenhart was the first to go during 1969, and Lenka Reinerová became Editor in Chief before being removed herself between 1969 and 1970. Reinerová would not be allowed to publish at all in Czechoslovakia until the fall of communism. The content of Czechoslovak Life in the 1970s reflects the increased censorship imposed in 1969, with articles about Czech industry, the health of good socialist citizens, and denunciations of the Spring as a failed right-wing coup that Czechs and Slovaks had recognized and rejected. No mention is made of the Warsaw Pact tanks. The censorship regime imposed after the Prague Spring marks the end not only of Dubček’s reforms, but also of Czechoslovak Life presenting “socialism with a human face” to a Western audience.

Further Reading:

Glossy Communism

You might also like:

The Refugees of ’68: The U.S. Response to Czechoslovak Refugees during Prague Spring

The Public Archive: Texas Czech Culinary Traditions

50 Years Since Prague Spring: Czechoslovak Dreams and Cold War Realities

The views and opinions expressed in this article or video are those of the individual author(s) or presenter(s) and do not necessarily reflect the policy or views of the editors at Not Even Past, the UT Department of History, the University of Texas at Austin, or the UT System Board of Regents. Not Even Past is an online public history magazine rather than a peer-reviewed academic journal. While we make efforts to ensure that factual information in articles was obtained from reliable sources, Not Even Past is not responsible for any errors or omissions.