For decades scholars of nineteenth- and twentieth-century Latin America had paid close attention to individual states and their relationship to national peasantries. This abiding interest stemmed from long-term academic investment in agrarian conflict and popular revolution in places like Mexico, Cuba, and Nicaragua. If social science and history could convincingly describe the social forces that produced revolutions in those places, however, they lacked broader explanatory power, since much of Latin America had toiled under similar conditions of state oppression and capitalist exploitation without exploding into peasant revolution. The years between the 1970s and the 1990s witnessed a gradual shift to comparative studies of the people who rebelled and those who did not. Richard Lee Turits’ fine new monograph, Foundations of Despotism, which examines state-peasant relations in the Dominican Republic under Trujillo, belongs to this latter trend.

In this extensively researched and cogently written work, Turits argues that the notoriously brutal Trujillo regime created lasting links with peasant communities in the rural hinterlands, which helped to solidify his thirty-year rule. Drawing on recent approaches to state-formation in Latin America that emphasize both political culture and contingency, Turits makes a compelling argument against the prevalent portrayals of the Trujillo regime as totalizing and “sultanistic.” Rather, Turits sees the Domincan state as improvisational, often internally incoherent, and legitimized largely through its symbolic and material investment in peasant land holding and independent farming. The author demonstrates that Dominican peasants received tangible benefits from their loyalty to the Trujillo regime (most importantly access to land, but also infrastructure, health care, education, etc.), and that they also used the state’s paternalist discourse in order to press their claims. Viewed this way, the over-the-top personalism of the regime and the relative “quiescence” of the rural majority make more sense. Turits explains the gradual crumbling of the Trujillo government between 1950 and 1961 as a result of the dictator’s sudden turn away from paternalist peasantism toward state sugar capitalism, along with a loss of support from both the Catholic Church and the U.S. government.

In this extensively researched and cogently written work, Turits argues that the notoriously brutal Trujillo regime created lasting links with peasant communities in the rural hinterlands, which helped to solidify his thirty-year rule. Drawing on recent approaches to state-formation in Latin America that emphasize both political culture and contingency, Turits makes a compelling argument against the prevalent portrayals of the Trujillo regime as totalizing and “sultanistic.” Rather, Turits sees the Domincan state as improvisational, often internally incoherent, and legitimized largely through its symbolic and material investment in peasant land holding and independent farming. The author demonstrates that Dominican peasants received tangible benefits from their loyalty to the Trujillo regime (most importantly access to land, but also infrastructure, health care, education, etc.), and that they also used the state’s paternalist discourse in order to press their claims. Viewed this way, the over-the-top personalism of the regime and the relative “quiescence” of the rural majority make more sense. Turits explains the gradual crumbling of the Trujillo government between 1950 and 1961 as a result of the dictator’s sudden turn away from paternalist peasantism toward state sugar capitalism, along with a loss of support from both the Catholic Church and the U.S. government.

Turits shows that the Trujillo regime established its legitimacy among peasants through broadly cultural means. To do so, he lays out the longue durée history of the nation’s rural people, mainly descendants of enslaved Africans who carved out an independent, pastoral existence in the Dominican hinterlands after the colonial sugar economy went bust in the late-sixteenth century. The unique structural and environmental conditions in the Dominican Republic—which suffered from little agrarian pressure and was spared the horrors of large-scale plantation agriculture after the initial bust—worked to produce a mobile, independent, and pastoral peasant population which consistently thwarted Dominican elites’ attempts to form a modern nation-state. Unlike his predecessors, though, Trujillo successfully integrated this troublesome element through a strategic mix of land distribution, authoritarian rule and state terror, and cultural politics. Carefully deployed carrots and sticks, then, turned pastoral nomads into sedentary, modernized peasant communities, which produced agricultural surpluses for sale on the world market. It should be noted, too, that Truijllo’s peasant-centered modernity required negotiations with both peasants and private landowners—foreign and domestic. Turits’ explorations of these negotiations reveal a regime that pursued an ad-hoc, equivocating policy of support of the peasantry and often failed the latter when it was up against powerful U.S. sugar interests.

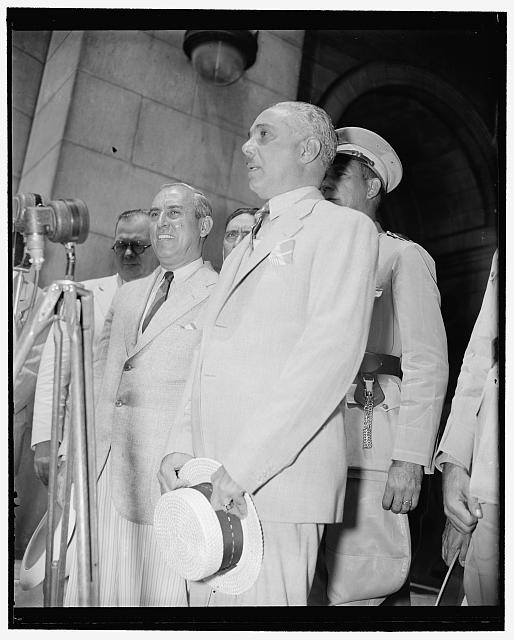

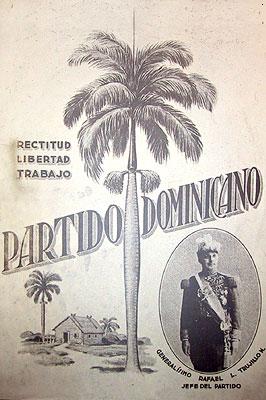

A young Raphael Trujillo (Image courtest of Wikimedia Commons)

A young Raphael Trujillo (Image courtest of Wikimedia Commons)

Nevertheless, Turits’ shows that the Trujillo state created lasting, though ambivalent, bonds with rural people that served to preserve an especially undemocratic regime for three decades. In many ways, this paradoxical support for a widely reviled and unquestionably ruthless dictator, which has lingered into contemporary memories of the trujillato, provided the impetus for the work in the first place. Indeed, Turits utilizes oral histories of elderly peasants in order to build a more nuanced cultural component to his otherwise materially oriented explanation. Here, he argues that Trujillo’s policies resonated with peasant traditions of “respeto,” or patriarchal order, and independence. While compelling in this light, these combined material and cultural factors seem less suitable to explain the role of the 1937 “Parsley Massacre”, in which the Trujillo regime turned suddenly and violently against Haitian immigrants on the frontier. In a work as carefully structured and logically argued as Foundations of Despotism, the section on the massacre seems to find Turits in a stretch to make the reckless incoherence of the massacre fit into a coherent framework. The same criticism may apply, as well, to the book’s final chapter, which attempts to explain the rapid and seemingly self-defeating fragmentation of the regime in terms of the broader argument about state formation and paternalist populism. That is, it seems that the “insanity” of the Trujillo state’s twilight years continues to defy systematic explanation.

Nevertheless, Turits has offered us a compelling and nuanced understanding of why Domincan peasants not only did not rebel, but actively endorsed the “sultanistic” rule of Rafael Trujillo throughout the bulk of his reign. His attention to material conditions, state terror, and cultural politics, while not entirely novel, could certainly translate to other settings and help us understand how “despotic” regimes more broadly have historically reproduced their power and negotiated popular acceptance.

You may also like:

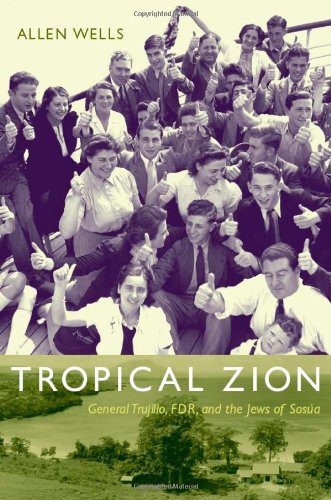

Lauren Hammond’s reviewon Trujillo’s Dominican Republic: “Tropical Zion.”

The horrific violence left as many as 15,000 dead. Trujillo apologists managed to justify the action nationally, but the massacre created an international public relations nightmare for the regime. Newspapers cited Trujillo’s ruthlessness and compared him to

The horrific violence left as many as 15,000 dead. Trujillo apologists managed to justify the action nationally, but the massacre created an international public relations nightmare for the regime. Newspapers cited Trujillo’s ruthlessness and compared him to

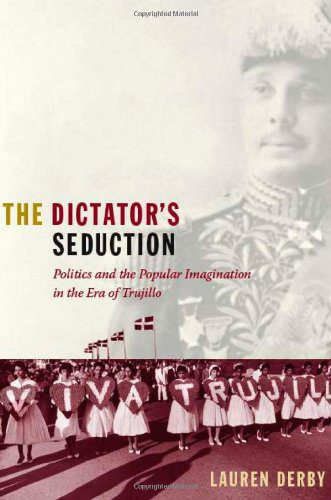

A light-skinned mulatto with Haitian ancestry, Trujillo rose from obscurity as a sugar plantation guard to establish one of Latin America’s most enduring dictatorships. His appetite for women was legendary and common belief held that he never sweated. Trujillo’s minions, and even foreign governments, lavished him with praise and an array of titles from Generalissimo to Benefactor of the Fatherland to Restorer of Financial Independence. However, outside portrayals of Trujillo as a make-up wearing megalomaniac and revelations of his regime’s oppression, many questions remain about the mechanisms of state power and relations between the Dominican populace, Trujillo, and the state. In The Dictator’s Seduction, Lauren Derby uncovers the cultural economy “that bound Dominicans to the regime.” She reinterprets the regime’s theatricality – pageants, parades, and the practices of denunciation and public praise – as critical in obscuring the inner workings of the regime and argues that the Trujillato gained and maintained the support of the masses, albeit in attenuated form, by creating a new middle class and co-opting Dominican understandings about the embodiment of race, gender, sexuality, and the process of community formation.

A light-skinned mulatto with Haitian ancestry, Trujillo rose from obscurity as a sugar plantation guard to establish one of Latin America’s most enduring dictatorships. His appetite for women was legendary and common belief held that he never sweated. Trujillo’s minions, and even foreign governments, lavished him with praise and an array of titles from Generalissimo to Benefactor of the Fatherland to Restorer of Financial Independence. However, outside portrayals of Trujillo as a make-up wearing megalomaniac and revelations of his regime’s oppression, many questions remain about the mechanisms of state power and relations between the Dominican populace, Trujillo, and the state. In The Dictator’s Seduction, Lauren Derby uncovers the cultural economy “that bound Dominicans to the regime.” She reinterprets the regime’s theatricality – pageants, parades, and the practices of denunciation and public praise – as critical in obscuring the inner workings of the regime and argues that the Trujillato gained and maintained the support of the masses, albeit in attenuated form, by creating a new middle class and co-opting Dominican understandings about the embodiment of race, gender, sexuality, and the process of community formation.