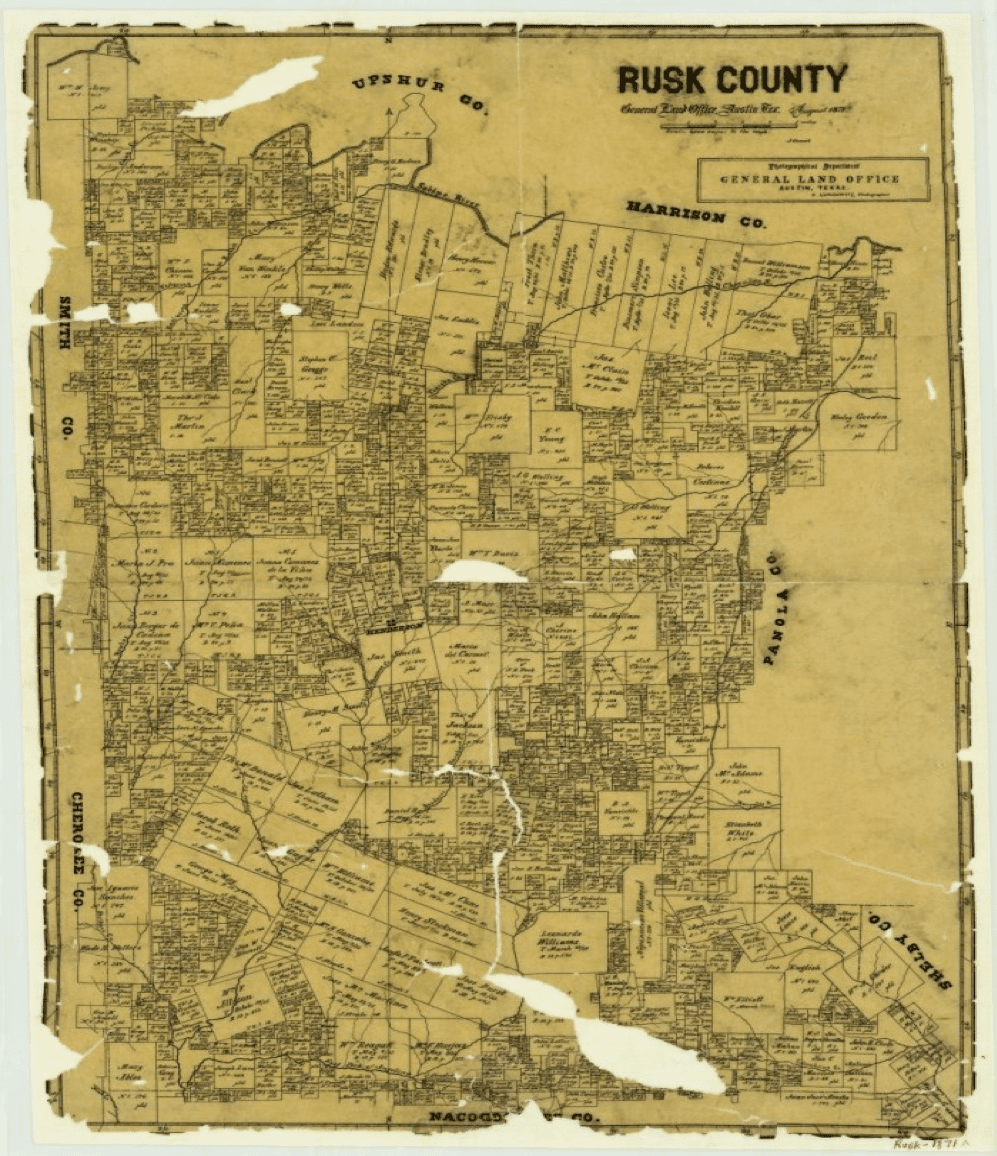

Originally from Macon, Alabama, Julien Sidney Devereux, Sr (1805-1856) moved to east Texas where he eventually purchased land in Rusk County. This plat would eventually become Monte Verdi, one of the highest producing cotton plantations in the state, where over fifty Africans were enslaved. The Devereux family papers and the maps of the Texas General Land Office, including Julian Devereux’s will (1852) and a plat map of Rusk County (1846-1861), yield rich information about the institution of slavery.

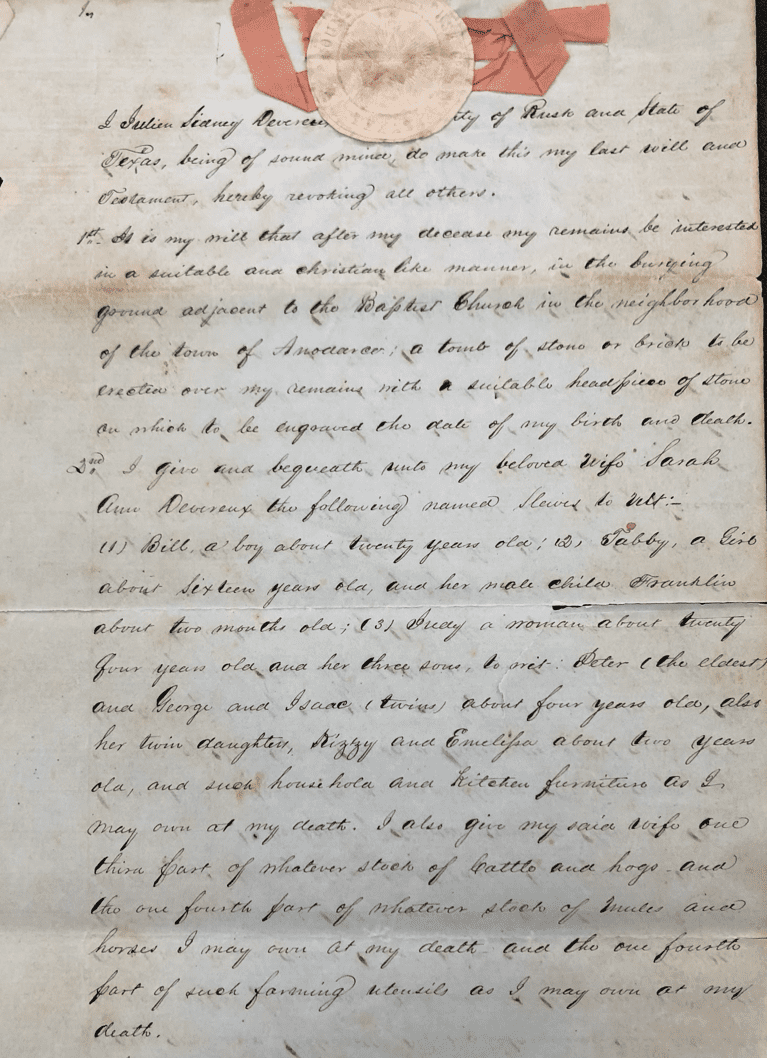

On May 7, 1852, Julien Devereux signed his final will and testament. Thirteen of the fourteen sections of his twelve-page will dealt explicitly with the institution of slavery. Sections two through six of his will present a rigid, hierarchical system to control the distribution of enslaved persons among his family members. Devereux named the slaves who, along with the furniture and cattle, were to be willed to his wife and daughter in sections two and three, respectively. Should his daughter not marry or bear children by the age of twenty-one, he noted that all willed enslaved people were to be turned over to his wife. In section four, he bequeathed a nineteen-year-old boy, a twelve-year-old girl, and “their increase” to one of his sons. The increase allotted to his son appears to allude to the arranged breeding of enslaved people and the enslavement of their unborn children. Section five established the equal distribution of Devereux’s remaining fifty-six enslaved persons and all of their future children among his remaining sons. Section six included three stipulations controlling his widow’s actions to ensure that his enslaved persons and property remained within his direct lineage. He declared that his wife must remain on the plantation and under the supervision of his chosen executors, that she could not sell any property or slaves during her lifetime, and that she would relinquish all willed property and enslaved people should she remarry.

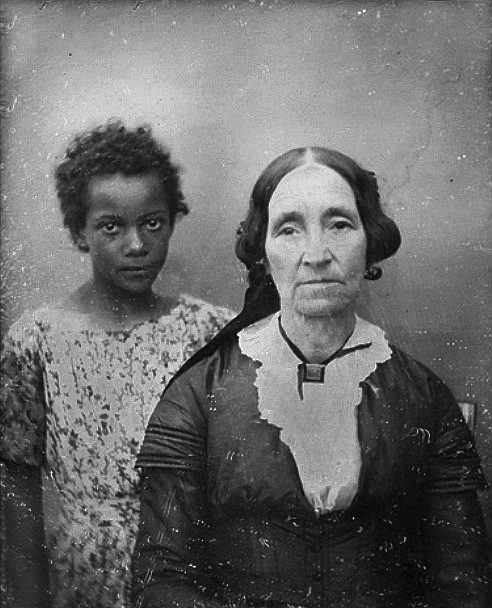

The peculiar affection for the enslaved also emerges in the will. In section eight, Devereux appeared to reward an enslaved man and woman for their “long and faithful service” by allowing them to nurse his children. In addition, Devereux declared that the enslaved should never be sold to pay debts because they are “family slaves.” Instead, he reserved over eleven hundred acres of land to be sold if necessary. Finally, Devereux declared that family slaves become fixed by his will thus demonstrating the way enslavement became predetermined and hereditary.

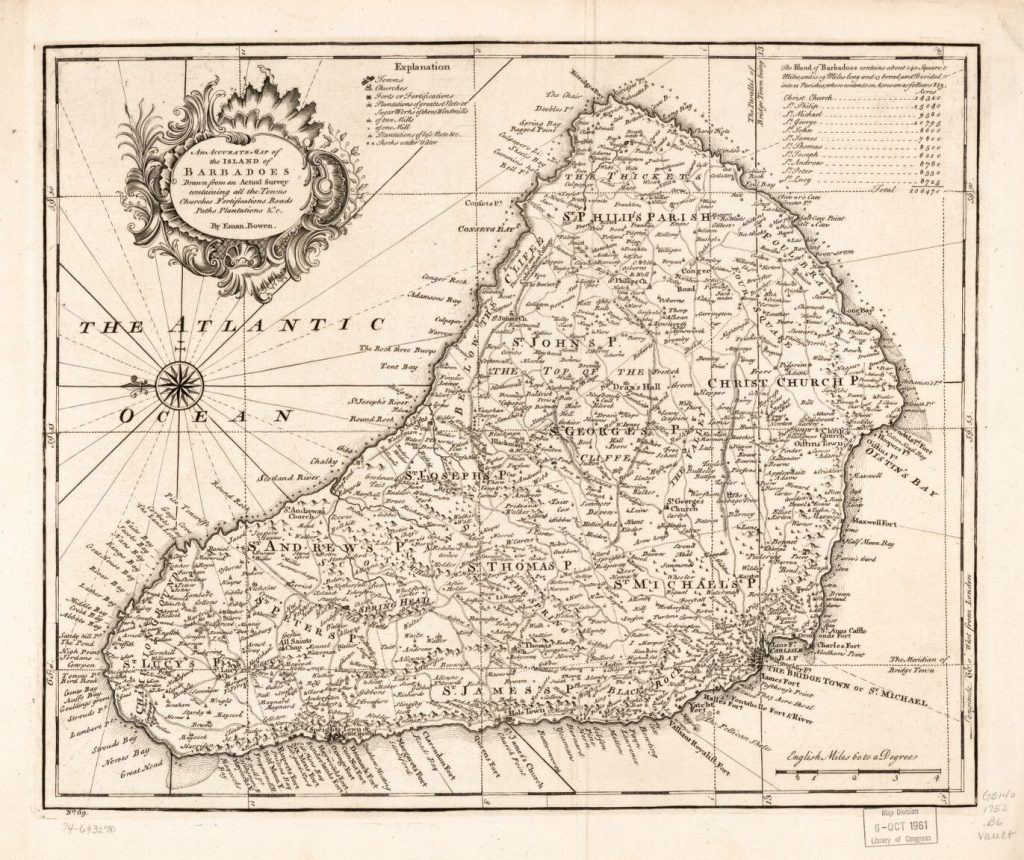

The accompanying county map incorporated in this analysis of Devereux’s will challenges some common assumption about institutional slavery. To shore up the distribution of public property, the Republic of Texas Congress formed the General Land Office (GLO) in 1836. This map of Rusk County was produced by the GLO and represents plats of property purchased between 1846 and 1861. The density of the map shows that few plats appear to be large; the majority of holdings appear to be quite small and crowded near others. Second, Devereux’s plantation had one of the largest enslaved populations in the state of Texas, at fifty-six. In Rusk County, plantations were not isolated, rural locales with hundreds of enslaved people, as if often assumed. This map shows an densely-settled region where the number of enslaved people would have been similar o that of the Devereux plantation at Monte Verdi.

Collectively, these documents illuminate numerous aspects about the institution of slavery in Texas on the eve of the Civil War.

Julien Sidney Devereux Family Papers, 1766-1908, 1931, 1941, Box 2N215, Will, 1852-1854 Dolph Briscoe Center for American History, The University of Texas at Austin. A Guide to the Julien Sidney Devereux Family Paper, 1766-1941; Volume/Box: 2n215

I Julien Devereux . . . State of Texas, being of sound mind, do make this my last will and testament, hereby revoking all others.

- It is my will that after my decease my remains be interested in a suitable and christian like manner, in the burying ground adjacent to the Baptist Church in the neighborhood of the town of _______; a tomb of stone or brick to be erected over my remains with a suitable headpiece of stone on which to be engraved the date of my birth and death.

- I give and bequeath unto my beloved wife Sarah Ann Devereux the following named slaves to ____: (1) Bill, a boy about twenty years old; 2) Gabby, a girl about sixteen years old, and her male child Franklin about two months old; 3) ____a woman about twenty four years old and her three sons, ____: Peter (the eldest), and George and Isaac (twins) about four years old, also her twin daughter, Kizzy and Emelisa about two years old, and such household and kitchen furniture as I may own at my death. I also give my said wife our ____ of whatever stock of cattle and hogs and ___ one fourth part of whatever stock of mules and horses I may own at my death and the one fourth part of such farming utensils as I may own at my death.

- I give and bequeath to my natural daughter Antoinette Devereux the following slaves, to wit: 1) Gino a man about twenty years of age; 2) Rhoda women about eighteen years of age and her two children to wit: Cynthia two years old and the female infant she now have about eight months old named ________________. I also give to Antoinette one horse, saddle and _______ one bed _____ and furniture and two cows and calves I also give said Antoinette her maintenance and education so hereafter provided. And should the said Antoinette be leaving no direct lineal heir of her body begotten then it is my will that said slaves and their increase shall revert to my child or children by my said wife Sarah Ann to be equally divided among them or their lineal heirs. And should said slaves die or any one or more of them before the said Antoinette shall arrive at the age of twenty one years, or before she may marry then it is my will that she should receive and have other slaves to be taken out of those hereafter bequeathed to my children by my wife of equal value with such as may so die, to be set apart to her by my executors.

- I will and bequeath to my natural son Sidney Devereux, two slaves, to wit: Joe a boy about nineteen years old and Joanna girl about twelve years old together with their increase. And I also bequeath to the said Sidney our horse, saddle and bridle: One bed, ____ and furniture and two cows and calves. And I also give the said Sidney his maintenance and education as hereinafter provided. And should the said Sidney die leaving no child or children or the descendants of child or children then it is my will and desire that said slaves shall revert to my children by my wife Sarah Ann, or their lineal heir to be equally divided between them. And should one or both of said slaves die before the said Sidney shall arrive at the age of twenty one years then it is my will that he shall have and receive other slaves or slaves in lieu thereof in like manner as herein before provided for Antoinette Devereux.

- I hereby will and bequeath the residual of my property real, personal and mixed, choses in action, effects and rights of whatever description among which ___estimate fifty six slaves to my two sons Albert and Julien Devereux by my present wife, together and in common with such other child or children as she may hereafter have by me to be equally divided between my said two sons and such other child or children as may so be done. If there shall be but one of said sons living at my death and no other child born, then he is to have all the property herein bequeathed to both: if both of said sons are living at my death and no other child born, then said property to be divided between them: if there shall be at my death said two sons and one or more other child or children of my present wife living or posthumous, then it is my desire that said property shall be equally divided between all of said children. And for greater certainty I here give the names of the slaves mentioned and intended to pass to said children by this my 5th bequeath to the best of my resolution, to wit, 1 Scott 2 Jack Shaw 3 Henry 4 Luoius 5 Martin 6 Lewis 7 ___ 8 July 9 Daniel 10 Stephen 11 Levin 12 Randal 13 July? 14 Little Jack 15 Amos 16 Charles 17 ___ 18 Tom 19 Anthony 20 Walton 21 Richmond 22 Green 23 Arthur 24 Pam 25 Little Jesse 26 Nelson 27 Dennis 28 Mason 29 Harrison 30 Aaron 31 Anderson 32 Robert 33 Cola Tabby 34 Mary 35 Henry 36 Lev Mariah 37 Katy 38 Marha 39 Amey 40 Matilda 41 Eliza 42 Dea’nah 43 Makalah 44 Sarah 45 Jane 46 Phebe 47 Jinny 48 Elmina 49 Jiney 50 Louisa 51 Penial 52 Charlotte 53 Little Amey 54 Katy’s child not named and 55 & 56 (two others names not recollected, together with all the increase of said slaves. This my 5th bequeath is made charged with and subject to the following restrictions, uses and conditions to wit: That my present wife Sarah Ann remain on the plantation where we now reside, and under the supervision of my executors as hereinafter directed carry on the plantation for the maintenance of herself and her children and the two natural children Antoinette and Sidney and for the education of her own children as well as the said Antoinette and Sidney. And that she may be able to do so. It is my will that she have the use of the said plantation negroes stock, mules, farming utensils and other ___property appertaining to a plantation during her natural life or widowhood with his exception that as my children ______attain to the age of twenty one years- or if-______ the legacies and property bequeath to them by this will is to be delivered over to them respectively provided that my present residences and land to the extent of two hundred acres including the slaves shall not be sold during the lifetime of my said wife. And should my said wife-Sarah Ann again marry it is my will that there be a complete separation of her property and interests in all things of a _____ character from those of my children.

- I desire and bequeath to my said wife and her children all the real estate which I may own and possess at my death to be equally divided between them that is to say if I shall have one or more child or children, by her she is to have a childs part of said real estate in value equal to the part or share of said child or children to be laid off so as to include our present residences. My residences as I desire here to explain, consists of the mansion house and other buildings and four thousand acres of land more or less attached thereto in different survey_____as the William & _______and other lying in one body. The division of said land here ____plateau to be fairly and equally made by my executors.

- In the event I leave no child or children by my present wife, living or posthumous at my death, then I will and bequeath the property and its increase herin before devised to such child or children to my said wife and the said Antoinette and Sidney Devereux to be equally divided between them that is to say said property is to be equally divided between my said wife, the said Antoinette and the said Sidney or their lineal descendants provided I leave no child or children in being or posthumous by my said wife or the direct lineal heirs of such child or children by my said wife. Said decision to be made between my said wife and the said Antoinette and the said Sidney in three equal parts share and share alike.

- In consideration of the long and faithful service of the old negro slaves Scott and Gabby hereinfore bequeathed to my new sons Albert and Julian it is my will and desire that from and after they be exempt from compulsory personal labor further than to give such attention as they may be able in nursing and taking care of my children after my death; and I further will and desire that the said Scott and Gabby shall be humanely treated and will provided for by my executors.

- It is my will and desire that all my just debts be paid before distribution of my estate takes place. And in providing for the maintenance of my children I estimate the profile of my plantation as being ______for those purposes and pay my just debts. If, however tho fund arising from my plantation is insufficient for all the _______ properties, and it is deemed necessary by my executors to sell any portion of my estate for the payment of my debts, it is my desire that none of my slaves shall be sold. They are family slaves it is my will that they so remain after my death. I hereby designate as property to be sold for the payment of debts if necessary two tracts of land to with: eleven hundred and seven acres the head right property of ____ Robert W Smith and Eight hundred and eighty acres known as the ____. I purchased of Doctor Elijah Doson or so much thereof as my executors may deem sufficient.

- Contrary to any wish desire or request of mine the legislation of the State of Texas at its last___ the second section of act entitled “an act changing the names of Antoinette _____ and Sidney May” which act was “approved January 3 1852.” said second section is in these words “That the said Antoinette Devereux and Sidney Devereux be and they are hereby declared capable in law of inheriting the property of their father Julien Devereux in the same manner as if they had been born in lawful wedlock – and that this act take effect and be in force from and after its passage”. Now, although it has long been my wish and desire that the names of the said Antoinette Scott and Sidney ___ should be changed as provided for by the first section of the above cited act, yet I never intended nor was it ever my will that they shall inherit my estate in the manner provided in the said second section . I do therefore now and forever hereafter by this my last will and testament most solemnly protest against the operation and effect of said second section of said act and desire that said second section may be appealed by act of said Legislature at the next session, the same having been passed without my knowledge consent or approbation and in direct violation of any wishes and desires. It is my will that the said Antoinette and Sidney be provided for and receive portions of my estate after my death only in such manner as is in this my last will and testament set forth and stated and in no other way.

- As I have before initiated, it is my will that a sufficient amount independent of the bequeath herein made be set apart and devoted to the maintenance and education of Antoinette Devereaux and Sidney Devereux, and my two sons Albert and Julien, and such other children of mine as may hereafter be born. And it is also my will that should the said Antoinette and Sidney or either of them die without lineal _____ of their body or bodies, the _______ of herein bequeathed is not in any way or under any circumstances to descend to or be inherited by any member of their mother family.

- My will is that my friend Doctor Peterson ___ Richardson be guardian of the person and property of my natural daughter Antoinette Devereux to superintend and direct her education and take care of her. And should my said wife deem it proper for Antoinette to be leave here I desire Doctor Richardson to take her and raise her. And it is my will and desire that my extended friend Col. William Wright Morris be the guardian of any natural son Sidney Devereux: as well of his person as his property and I desire that said Morris will consider the said Sidney wholly in his care and under his charge and permit him to ramble or wander off so as to become identified with his mothers people: That he will superintend the education and moral culture of the said Sidney and in a special manner prepare his mind for the study of the law by giving a proper direction to this education.

- It is my will that none of my slaves be sold. With due exception they are all family negroes, and my desire is that they so remain under the ____ plateau distribution fixed by this will: that they may be humanely treated and will be taken care of by those who may succeed me in the ownership of them.

- I do herby appoint my wife Sarah Ann Devereux, John Laudrew, Col. William Wright Morris, Doctor Peterson T. Richardson, and Doctor William M. ____ of Rush County and Doctor James H. ____ of Nagadoches County Texas (my trust worthy friends) my executors of this my last will and testament to execute and carry out all the terms and provisions of the _____. And it is my will that they or either one of them shall not be required to give bond and security as a condition to entering or the discharge of the duties herby imposed. It is also____my will and direction that no other action shall be had in the County Court in relation to the settlement of the estate herin disposed of then the probate and registration of this will and testament and a return of inventory of said estate. It is my desire and will that my wife Sarah ____ by the council and advice of any one or more of my other executors, as she may choose will take upon herself the supervision of my plantation for the purposes expressed in the will. That aided by my other executors she will attend to the hiring of overseers, the sale of produce, the investing of the proceeds of the plantation: That with the aid of said executor she will plan improvement of my plantation, preserve and take care of property, and above all she will attend strictly and carefully to the education of my two sons Albert and Julien and such other children as she may have by me.

I hereby appoint the said Sarah Anne Devereux guardian of the persons and property of my said sons Albert and Julian and such other child or children as she may have by me, and in case she should die then it is my will that Doctor Peterson T. Richardson will take the guardianship of said two sons and such other children as she may have as aforesaid.

The foregoing will of twelve and a half pages signed sealed and published in our presence and in the presence of each other. The foregoing twelve and a half pages contain my last will and testament executed at the town of Henderson on this 7th day of May AD 1852.

–Julien Sidney Devereux

![]()

Image 1

Image 2

Image 3

Image 4

Image 5

Image 6

Image 7

Image 8

Image 9

Image 10

Image 11

Image 12

Bibliography

Gomert, A. & Lungkwitz, Herman. Rusk County, map, 1871; (https://texashistory.unt.edu/ark:/67531/metapth89173/: accessed October 12, 2019), University of North Texas Libraries, The Portal to Texas History, https://texashistory.unt.edu; crediting Texas General Land Office.

Julien Sidney Devereux Family Papers, 1766-1908, 1931, 1941, Box 2N215, Will, 1852-1854 Dolph Briscoe Center for American History, The University of Texas at Austin

You might also like:

The Enslaved and the Blind: State Officials and Enslaved People in Austin, Texas

Slavery World Wide: Collected Works from Not Even Past

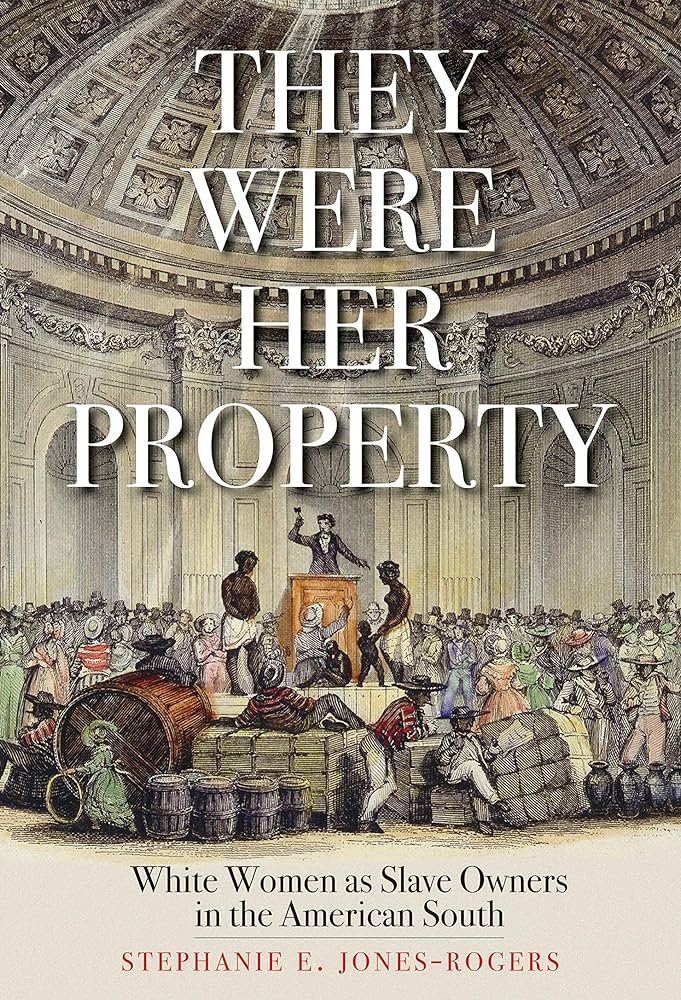

White Women and the Economy of Slavery

The views and opinions expressed in this article or video are those of the individual author(s) or presenter(s) and do not necessarily reflect the policy or views of the editors at Not Even Past, the UT Department of History, the University of Texas at Austin, or the UT System Board of Regents. Not Even Past is an online public history magazine rather than a peer-reviewed academic journal. While we make efforts to ensure that factual information in articles was obtained from reliable sources, Not Even Past is not responsible for any errors or omissions.