This week, Jeremi and Zachary are joined by Jonathan Alter to discuss the upcoming Democratic National Convention.

Zachary sets the scene with his poem entitled “When They Go Marching in Chicago”

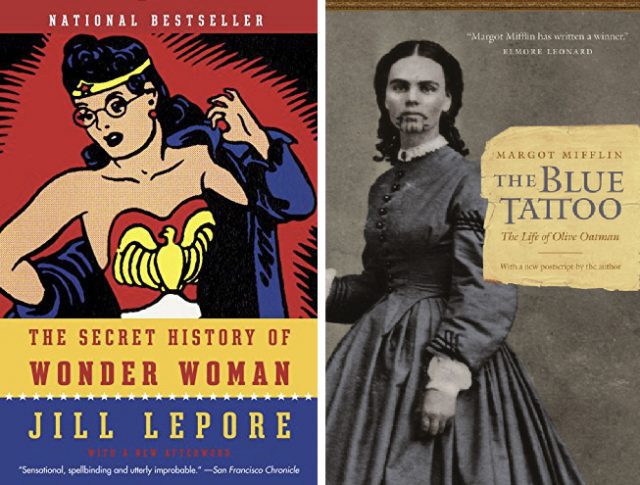

Jonathan Alter is an award-winning author, political analyst, documentary filmmaker, columnist, television producer, and radio host. He is the author of numerous books, including: His Very Best: Jimmy Carter, a Life; The Center Holds: Obama and His Enemies; The Promise: President Obama, Year One; and The Defining Moment: FDR’s Hundred Days and the Triumph of Hope.” His new book is: American Reckoning: Inside Trump’s Trial – and My Own.