On the eve of the Civil War, an advertisement appeared in the Texas Almanac announcing the sale of five enslaved people at the Stringer’s Hotel.

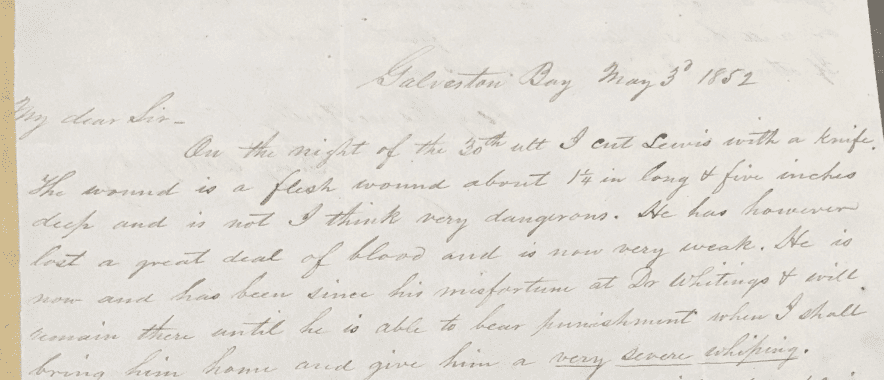

“Negroes For Sale––I will offer for sale, in the city of Austin, before the Stringer’s Hotel, on the 1st day of January next, to the highest bidder, in Confederate or State Treasury Notes, the following lot of likely Negroes, to wit. Three Negro Girls and two Boys, ages ranging from 15 to 16 years. The title to said Negroes is indisputable” —The Texas Almanac, Austin December 27th, 1862

This hotel was one of the many businesses in Austin using enslaved labor, a commonplace practice that extended to every part of Texas. However, urban slavery in Austin differed substantially from slavery on the vast plantations that stretched across Texas’ rural geography. Unlike rural planters, urban slaveholders were largely merchants, businessmen, tradesmen, artisans, and professionals. The urban status of these slaveholders in Austin meant that enslaved people performed a wide variety of tasks, making them highly mobile and multi-occupational. Austin property holders, proprietors, and city planners built enslaved labor not only into the city’s economy, but into its very physical space to meet local needs. This examination of the Stringer’s Hotel provides a brief window for looking into Austin’s history of slavery and perhaps the history of enslaved people in the urban context.

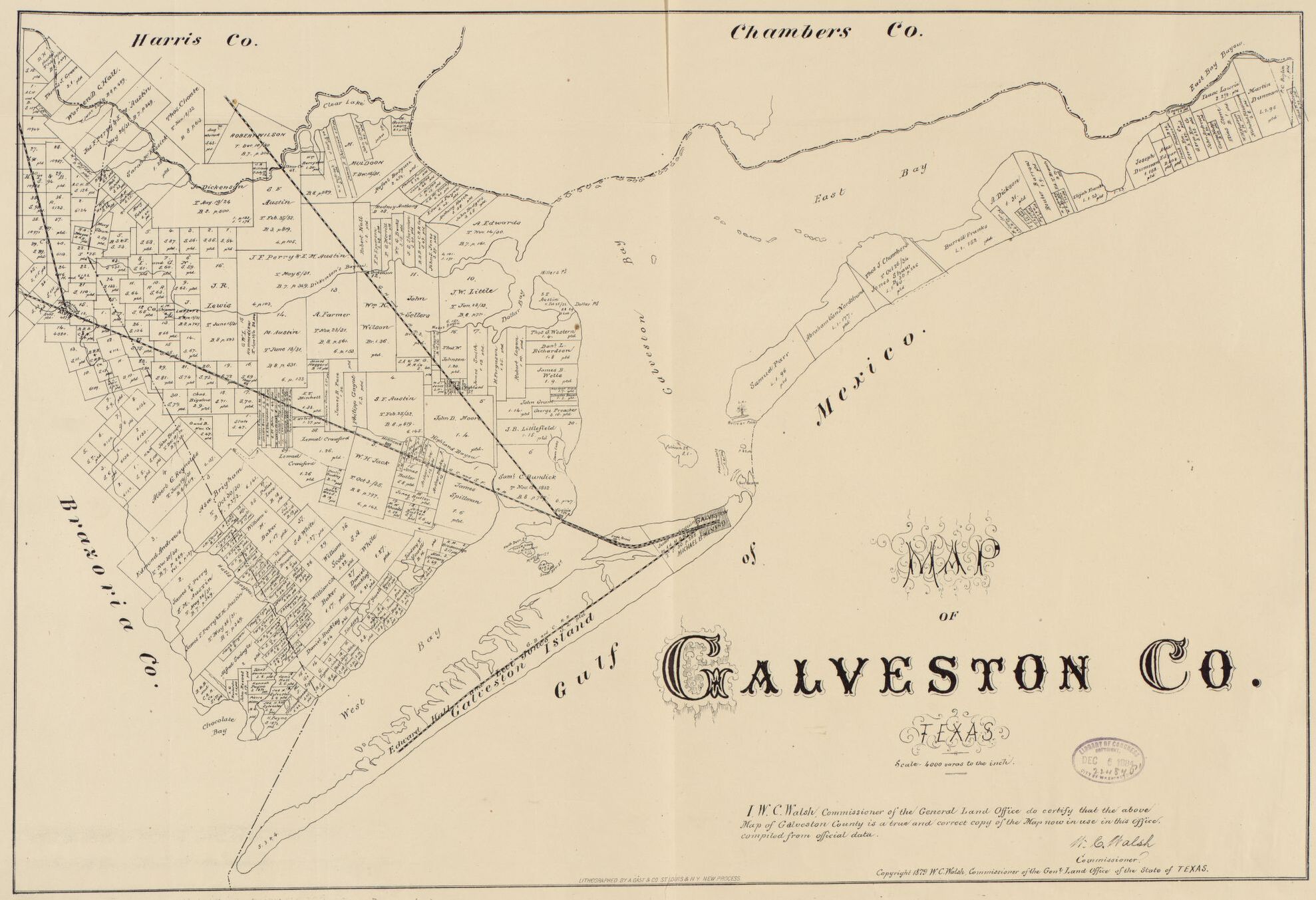

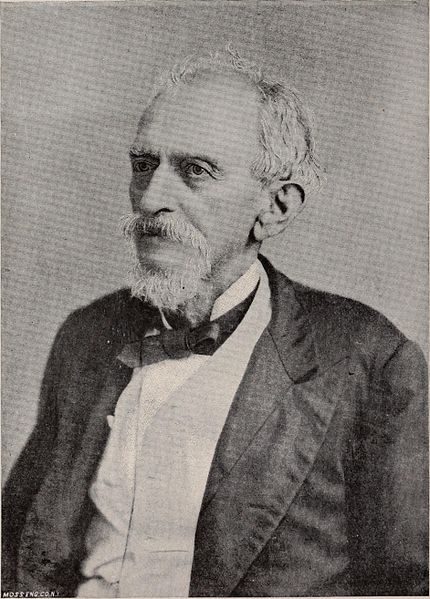

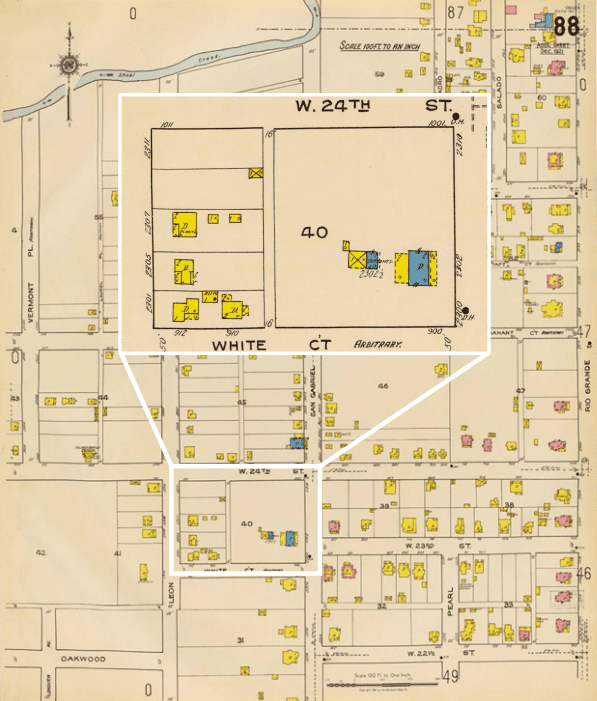

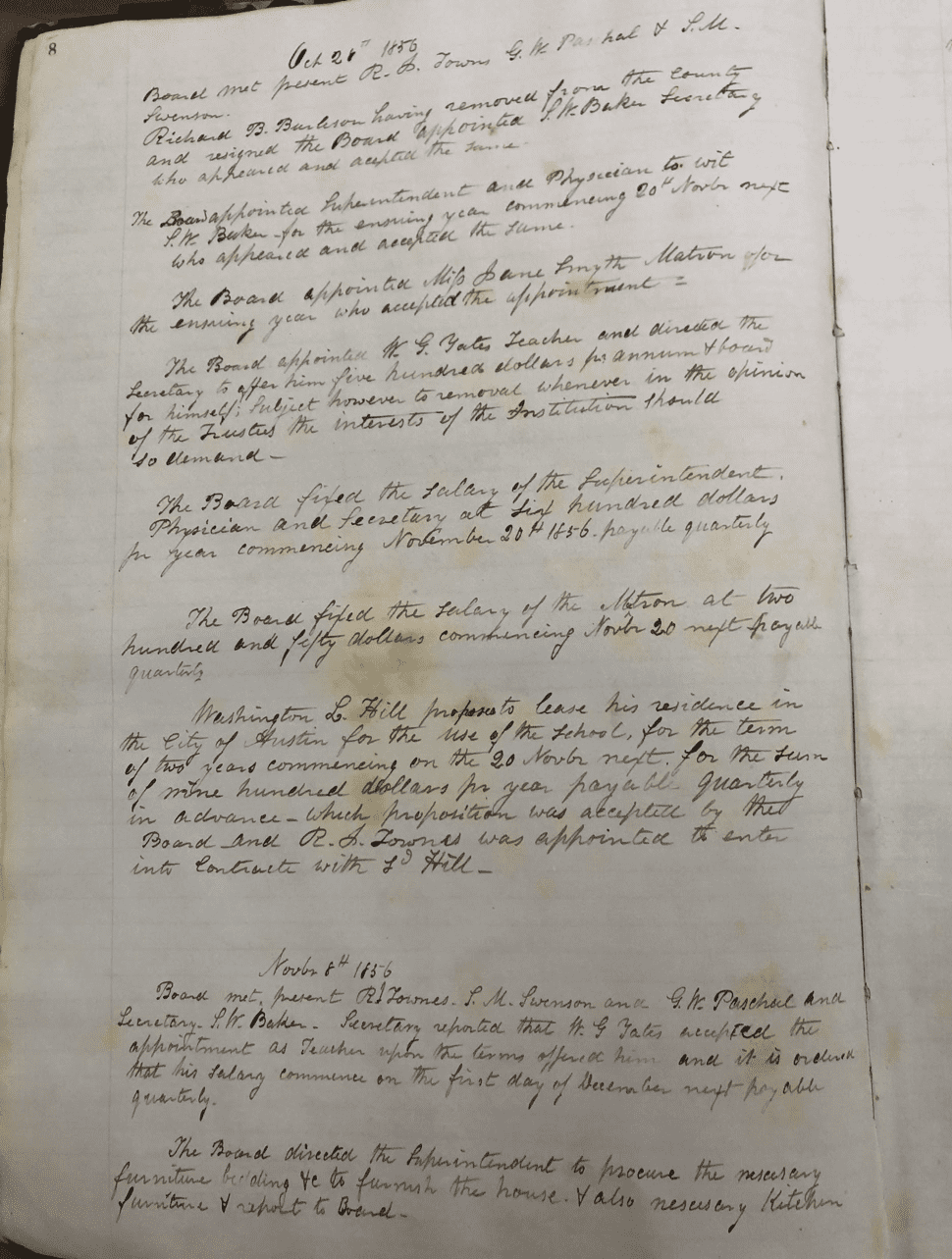

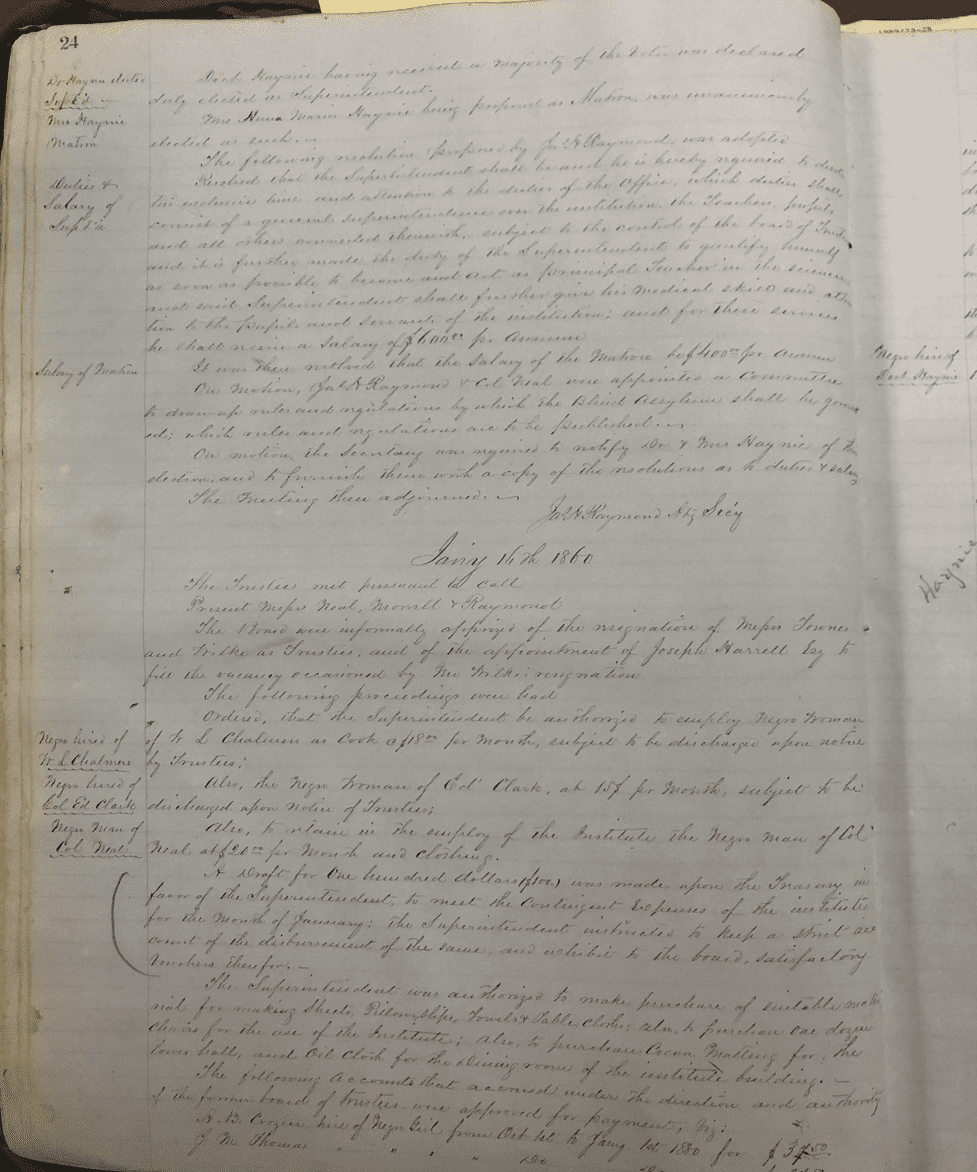

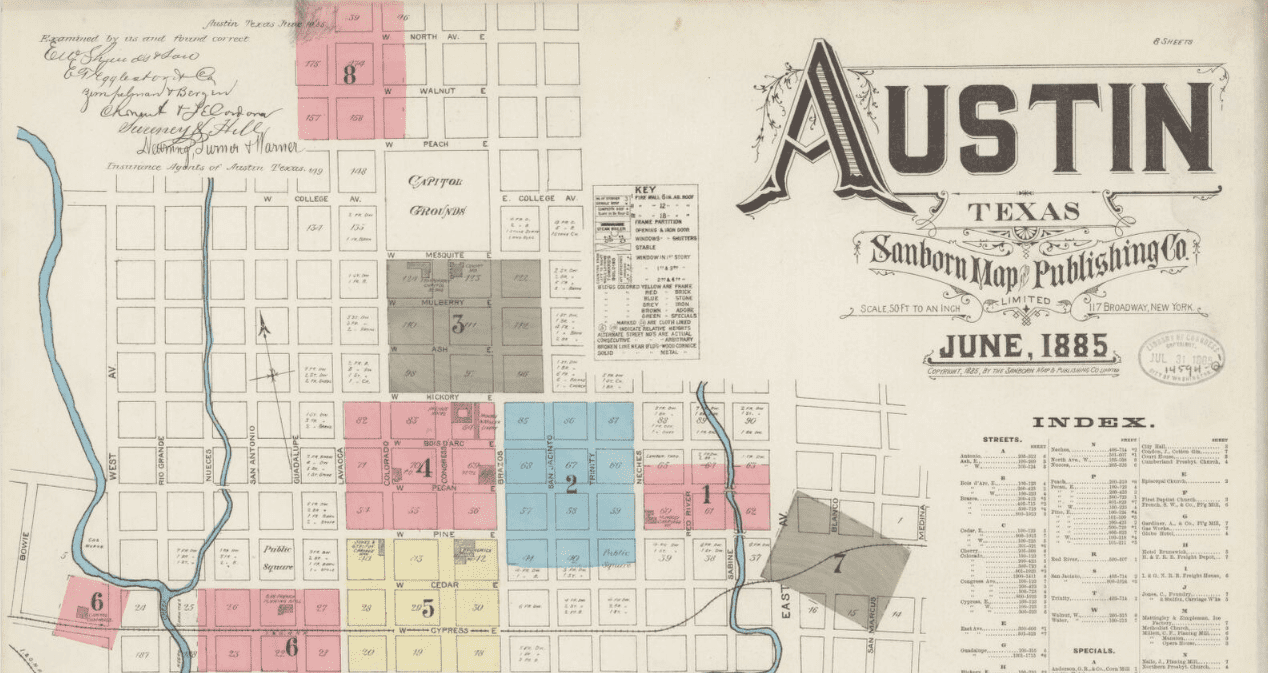

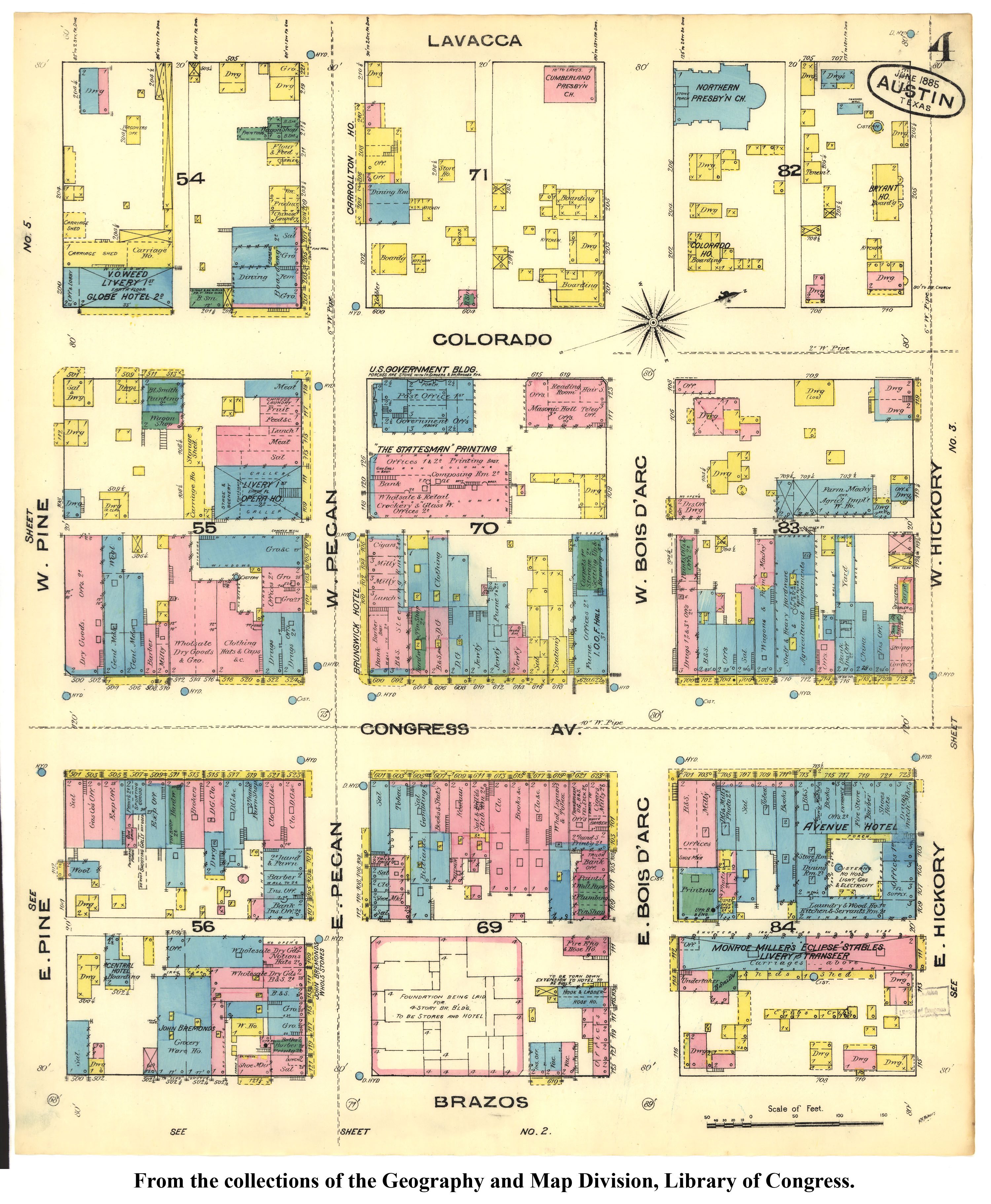

On September 3, 1850, Swante Magnus Swenson purchased a city lot in Austin. In 1854, he built the Swenson Building on Congress Avenue where the current Piedmont Hotel stands today. Inside the building, on the first floor, were a drug store, a general goods store, a hardware store, and a grocery store; a hotel, (named the Avenue Hotel but locally known as the Stringer’s Hotel) was located on the upper two levels of the building. The Travis County Deeds Records show that sometime later, Swenson leased the hotel to a John Stringer, giving the hotel its name “the Stringer’s Hotel.” An 1885 Austin city Sanborn map of the Swenson Building shows that Swenson had a room built for “servants” in the hotel portion of the building. There is no documentation detailing whether enslaved people stayed in that room since the Sanborn map is dated twenty years after the Civil War. However, an 1889 Sanborn map shows that Swenson had the Stringer’s Hotel remodeled to remove the room for “servants,” which suggests that enslaved people originally potentially stayed there, given that “servant” and “dependency” were variant terms used for “slave” in urban spaces. The National Register of Historic Places Inventory notes that businesses on Congress Avenue did not have the financial capacity to maintain, let alone remodel, their properties right after the Civil War. This explains the twenty-year delay to remove the said “servants” room, no longer utilized by enslaved people in the 1880s. Further evidence also shows that Swenson himself had strong ties to slavery in Texas.

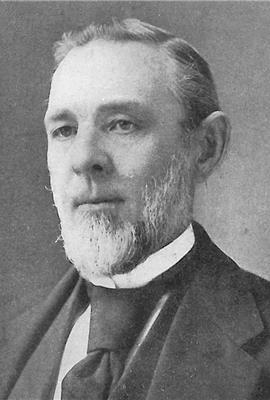

S. M Swenson was born in Sweden and came to New York as an immigrant in 1836 at the age of twenty. A few years after his arrival, Swenson worked as a mercantile trader. Through his trade dealings in the south, he befriended a slaveholder by the name of George Long, who then hired Swenson to work at his newly relocated plantation in Texas. A year later, when Long died due to poor health, Swenson married his widow, who then too died of tuberculosis three years later. By 1843, Swenson became a full-scale slaveholder in Texas through inheriting his now-deceased wife’s plantation. In 1848, he enlarged his property holdings by purchasing the adjoining plantation and expanding his cotton crop. In 1850, along with purchasing 182 acres a few miles outside of Austin, he bought the lot on Congress Avenue and constructed the Swenson Building and inside, the Stringer’s Hotel.

There are no records that detail the lives of enslaved people at the Stringer’s Hotel but other sources show that slaveholders expected slaves to fill a variety of roles in running their establishments on Congress Avenue. In his book, a Journey Through Texas, Frederick Olmstead describes his encounter with an enslaved woman who was responsible for tending to the hotel’s patrons along with upkeep and building maintenance. These slaves were also responsible for running errands and transporting goods. Many slaves also lived and traveled to and from homes and communities that formed on the outskirts of town. Traveling to and from their labor obligations or social engagements in their free time illuminates the various networks of movement created by the enslaved. Hence, given their relative independence, expectations, and responsibilities, it is not impossible to imagine enslaved people taking on leading roles in running the Stringer’s Hotel and other establishments in Austin.

The analysis of the Stringer’s Hotel through Sanborn maps and other qualitative sources illuminates the roles and occupations of enslaved people in Austin’s urban space. Unlike the enslaved people confined to the private domain of plantation estates, urban slaves worked in spaces with considerable mobility, meeting the needs of their owners and to fulfill their own social lives. Perhaps mapping the movement of enslaved people in this way, could allow for further interpretations of possible realities and lived experiences of enslaved people that archival texts obscure and make difficult to see.

Sources

- “Negroes for Sale.” The Texas Almanac. December 27, 1862, 1 edition, sec. 34.

- “Texas General Land Office Land Grant Database”, Digital Images, Texas General Land Office, Entry for Swenson, S M, Austin City Lots, Travis Co., TX, Patent no 429, vol.1

- “Austin 1885 Sheet 5,” Sanborn Fire Insurance Maps, Map Collection, Perry-Castañeda Library, Austin, Texas.

- Olmsted, Frederick Law. A Journey through Texas: or, A Saddle-Trip on the Southwestern Frontier. Austin: University of Texas Press, 1989: 50;

- Austin City Sanborn Map, 1885;

- Bullock Hotel. Photograph, University of North Texas Libraries, The Portal to Texas History, accessed December 3, 2019

Additional Readings

- “Bullock House.” The Handbook of Texas Online. Texas State Historical Association, June 12, 2010.

- Gail Swenson. “S. M. Swenson and the Development of the SMS Ranches,” M.A. thesis, University of Texas, (1960).

- Gage, Larry Jay. “The City of Austin on the Eve of the Civil War.” The Southwestern Historical Quarterly 63, no. 3 (1960).

- Kenneth Hafertepe. “Urban Sites of Slavery in Antebellum Texas” in Slavery in the City, Edited by Clifton Ellis and Rebecca Ginsburg, University of Virginia Press. (2017)

- Jason A. Gillmer. Slavery and Freedom in Texas: Stories from the Courtroom, 1821-1871. Athens: The University of Georgia Press, (2017)

You might also like:

Documenting Slavery in East Texas: Transcripts from Monte Verdi

Slavery World Wide: Collected Works from Not Even Past

Love in the Time of Texas Slavery

The views and opinions expressed in this article or video are those of the individual author(s) or presenter(s) and do not necessarily reflect the policy or views of the editors at Not Even Past, the UT Department of History, the University of Texas at Austin, or the UT System Board of Regents. Not Even Past is an online public history magazine rather than a peer-reviewed academic journal. While we make efforts to ensure that factual information in articles was obtained from reliable sources, Not Even Past is not responsible for any errors or omissions.