At the close of his presidency in 1999, Nelson Mandela praised Mohandas Gandhi for believing that the “destiny” of Indians in South Africa was “inseparable from that of the oppressed African majority.” In other words, Gandhi had fought for the freedom of Africans, setting the pattern for his later effort to liberate India from British rule.

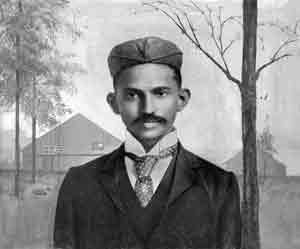

Nothing could be more misleading. Gandhi’s concern for the African majority — “the Kaffirs,” in his phrase — was negligible. During his South African years (1893-1914), argue Ashwin Desai and Goolam Vahed in “The South African Gandhi,” he was far from an “anti-racist, anti-colonial fighter on African soil.” He had found his way to South Africa mainly by the accident of being offered a better job there than he could find in Bombay. He regarded himself as a British subject. He aimed at limited integration of Indians into white society. Their new status would secure Indian rights but would also acknowledge white supremacy. In essence, he wanted to stabilize the Indian community within the stratified system that later became known as apartheid.

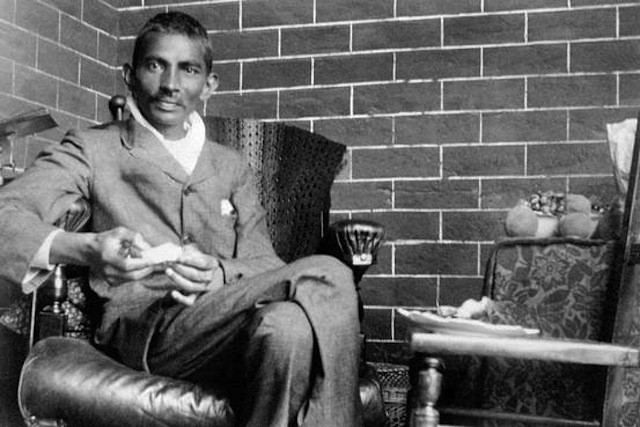

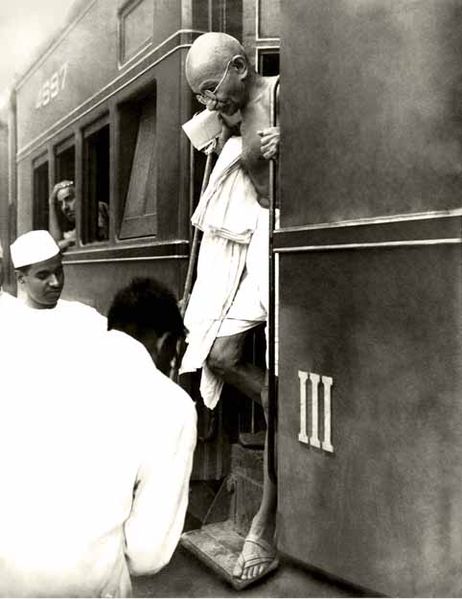

Gandhi’s two decades in South Africa did enable him to perfect the methods and aims of nonviolent resistance, but he practiced them solely on behalf of Indians. Gandhi was especially concerned with the indentured laborers of the sugar plantations in Natal, where the Indian population since the mid-19th century had grown to some 150,000, outnumbering whites. From the time of his arrival, he suffered such indignities as being forced off a train even though he held a first-class ticket and being pushed from the sidewalk into the gutter. But he remained loyal to the ideals of the British Empire, to, in his words, its “spiritual foundations.”

Gandhi’s principal adversary was Jan Christian Smuts. They were born a year apart, Gandhi in 1869 and Smuts in 1870. Both studied law in England. Smuts received highest honors at Cambridge. Though leading a lonely existence, he established lifelong contact with some of Cambridge’s more prominent intellectuals. By contrast, Gandhi acquired legal credentials while becoming acquainted with Helena Blavasky, the occultist and founder of the Theosophical Society, and with Annie Besant, another theosophist, with whom Gandhi discussed “the universal brotherhood of humanity.” Both Gandhi and Smuts shared the assumption that black Africans were simply, in Smuts’s summation, “barbarians.”

They fought on the opposite sides of the Boer War (1899-1902). Smuts rose to the rank of general, and Gandhi waged one of his most conspicuous campaigns on behalf of the British. He organized an “ambulance corps” of no fewer than 11,000 Indians, who helped wounded soldiers find their way to field hospitals, often by bearing them on stretchers. In the fierce battle of Spion Kop in Natal, Gandhi, with the discipline of a sergeant major, led his volunteers through rough terrain in blistering heat and heavy fire to save British lives. The Indian volunteers found the terrain so rough that stretchers proved impossible to use, so injured soldiers had to be carried individually. Gandhi’s bravery proved that he was willing to sacrifice his own life to save the lives of others and, in this case, to further the purposes of the British Empire.

Gandhi was never naïve enough to think that the Indian communities in Durban and Johannesburg would achieve social equality with whites. But they were, he believed, entitled to legal protection. The viceroy in India agreed with Gandhi. The status of overseas Indians was a sensitive issue. The power and influence of the Raj lent force to the cause of upholding the rights of British subjects—Indians—in South Africa.

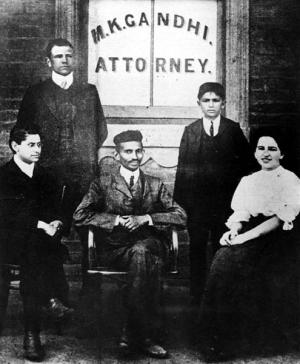

Gandhi’s legal credentials enabled him to practice law in South Africa. He challenged the government with petitions, thereby raising issues such as the right of Indians to own property. His success in organizing protest movements brought him to such prominence that he was able to meet with high-ranking officials, including Smuts, by then on his way to becoming prime minister.

Gandhi helped lead the two Indian rebellions of the era in South Africa, one in 1906 and the other in 1913. Both had origins in complaints about working conditions and the ambiguous status of Indian immigrants. In 1906, Indians protested against the Black Act, which required them to be fingerprinted—a practice reserved in India for common criminals. At one point Gandhi was briefly jailed, on Smuts’s own orders, as a result of his followers turning peaceful protests into riots.

When Gandhi eventually met with Smuts, they reached agreement, according to Gandhi, that the petty restrictions of the Black Act would be repealed. Smuts did not believe that he had made any fundamental concessions. In fact many of the restrictions were not repealed but recast sufficiently, so Smuts thought, to meet Gandhi’s satisfaction. He had not taken notes and failed to catch some of Gandhi’s exactitude. Gandhi later declared that he had been deceived. At their next and last meeting, some seven years later, Smuts took care precisely to transcribe all legal and other points.

The revolt of 1913 arose over the question of sending Indian dissidents back to India if they protested about wages or rights to property. In this action, the authors argue, Gandhi perfected the revolutionary technique of nonviolent resistance. At one point he led 13,000 Indians in protest. Gandhi proclaimed victory. Yet Smuts deftly secured important points regarding immigration and land ownership.

Gandhi was capable of spontaneous goodwill, as he demonstrated not only with Smuts but also later with Lord Irwin (Halifax) in India. In both cases, he characteristically laughed at his own inconsistencies and reaffirmed his faith in the ideals of the British Empire. He inspired intellectual and emotional bonds. Both sides could at least try to comprehend their differences and attempt to forge mutual respect. But it was an undertaking that had nothing to do with the African majority. Smuts believed that he could make minor concessions on such matters as passports and minimal labor laws, which persuaded Gandhi that Indians had secured legal protection.

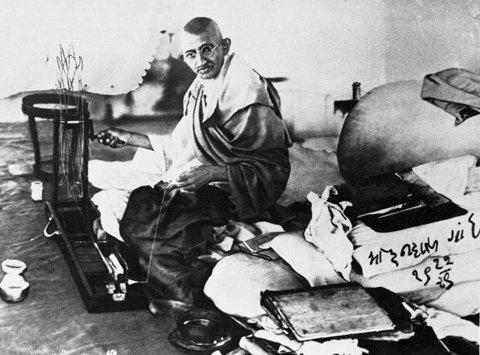

When Gandhi left South Africa in 1914, he was hailed as the Mahatma (Great Soul). He thereafter wore a loincloth and shawl, looking not much different from the way Churchill famously described him later as a fakir striding “half-naked” up the steps of the viceroy’s palace.

“The South African Gandhi” deals comprehensively with Gandhi’s decisive two decades in South Africa. It complements Perry Anderson’s “The Indian Ideology” (2013), which explains how Gandhi later treated the Dalits, or Untouchables, much as he had dealt with black Africans.

For my taste, the book’s tone is too academic, but the authors use sound evidence and argue their case relentlessly—Gandhi’s vision did not include the majority of the people in South Africa, the Africans themselves. Gandhi was consistent, but in ways quite at variance with the general belief that he championed all parts of society, whether in South Africa or, in regard to caste, in India. “The South African Gandhi” helps explain the complexity and contradictions of Gandhi’s personality while emphasizing the way in which he became a symbol of peaceful means to resolve conflict.

This article was originally published in the Wall Street Journal on January 10, 2016.

You may also like:

Roger Louis Recommends Five Books on the End of the British Empire

And these book reviews on Not Even Past:

- Gail Minault on The Great Partition: The Making of India and Pakistan by Yasmin Khan (2008).

- Dharitri Bhattacharjee on Gandhi: Prisoner of Hope by Judith M. Brown (1989).

- Sundar Vadlamudi on Great Soul: Mahatma Gandhi and his Struggle with India by Loseph Lelyveld (2010)

Perhaps aware of this difficulty, Joseph Lelyveld sets himself a modest goal to “amplify rather than replace the standard narrative” of Gandhi’s life. The

Perhaps aware of this difficulty, Joseph Lelyveld sets himself a modest goal to “amplify rather than replace the standard narrative” of Gandhi’s life. The