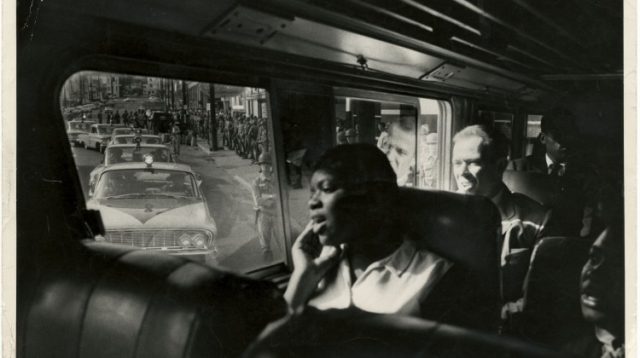

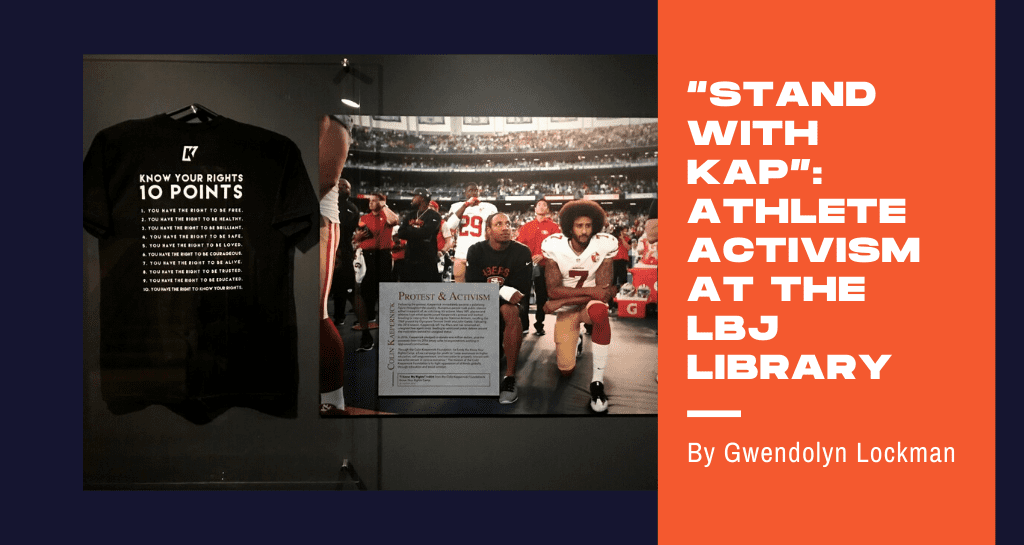

The Lyndon B Johnson Presidential Library opened “Get in the Game,” a timely exhibit on the intersection of social justice and sports, on April 21, 2018. In 2014, a new wave of athlete activism began in the United States. That year, NBA teams donned “I Can’t Breathe” shirts during warm ups to protest the police brutality against Eric Garner. In the summer of 2016, the WNBA joined the conversation with the “Change Starts with Us—Justice & Accountability” and #BlackLivesMatter, #Dallas5, #__ demonstrations by the Minnesota Lynx and New York Liberty. The current moment is most defined, of course, by Colin Kaepernick’s national anthem protests that began in the 2016 NFL preseason. “Get in the Game” charts a legacy of barrier-breaking and justice-seeking athletes from the late 19th century to the present with an emphasis on the current relationship between athlete activism and American politics.

The exhibit is remarkably comprehensive, especially for a small-scale and brief installation (the exhibit closes January 13, 2019). Visitors will find a wide selection of sports represented—horse racing, football, baseball, basketball, track and field, boxing, tennis, golf, and fencing—and attention to gender, race, media, player salaries, and social justice. Guests should be keen to linger in the center room of the exhibition, where curatorial care and intentionality is reflected in an exceedingly well communicated examination of Jackie Robinson’s post-baseball activism and the 1968 Olympic Project for Human Rights.

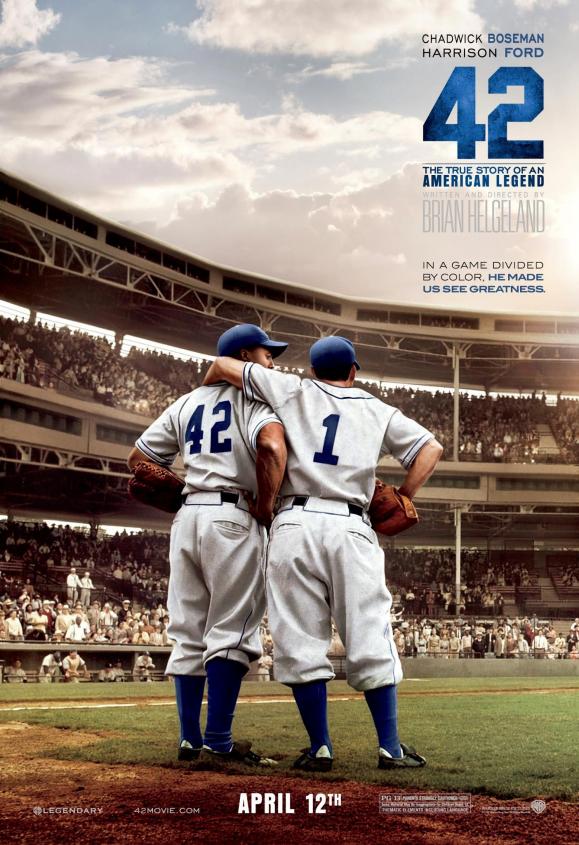

While most Americans are familiar with Jackie Robinson as a figure and the brief details of his early career with the Brooklyn Dodgers, few popular versions of his story reflect on the later years of his baseball career and after he retired. It is not popularly discussed that Robinson was among the crowd at the March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom in 1963, nor that he campaigned for Richard Nixon.

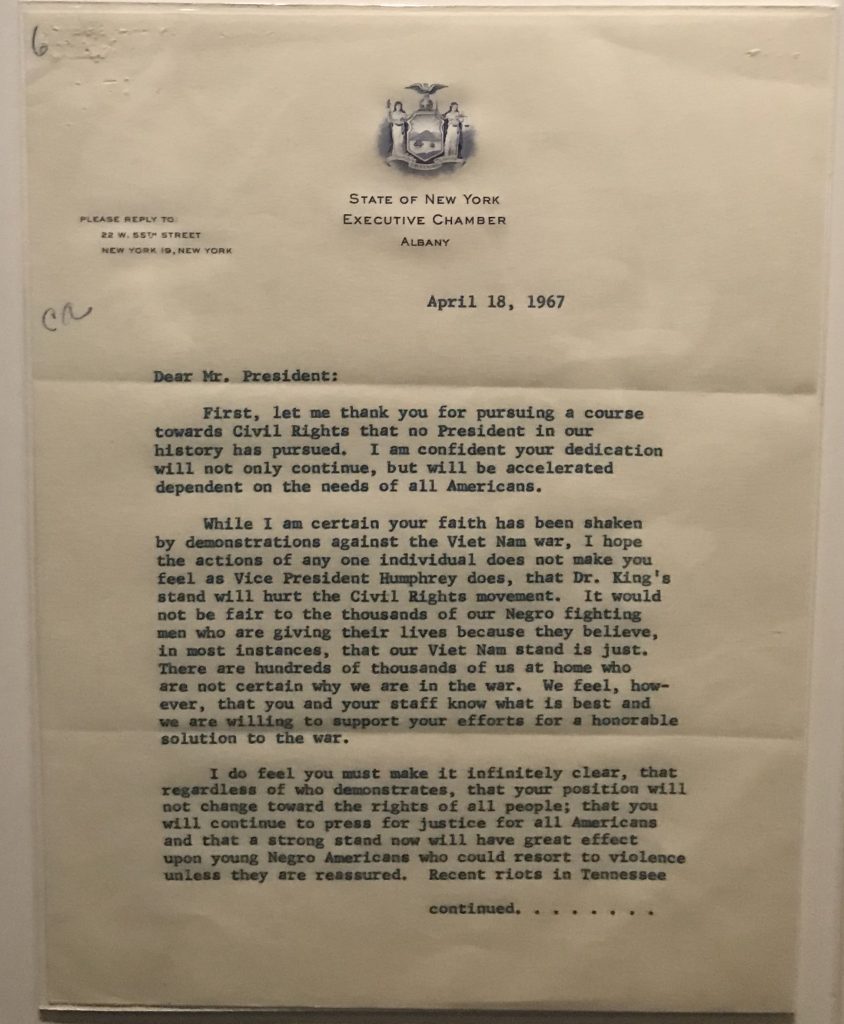

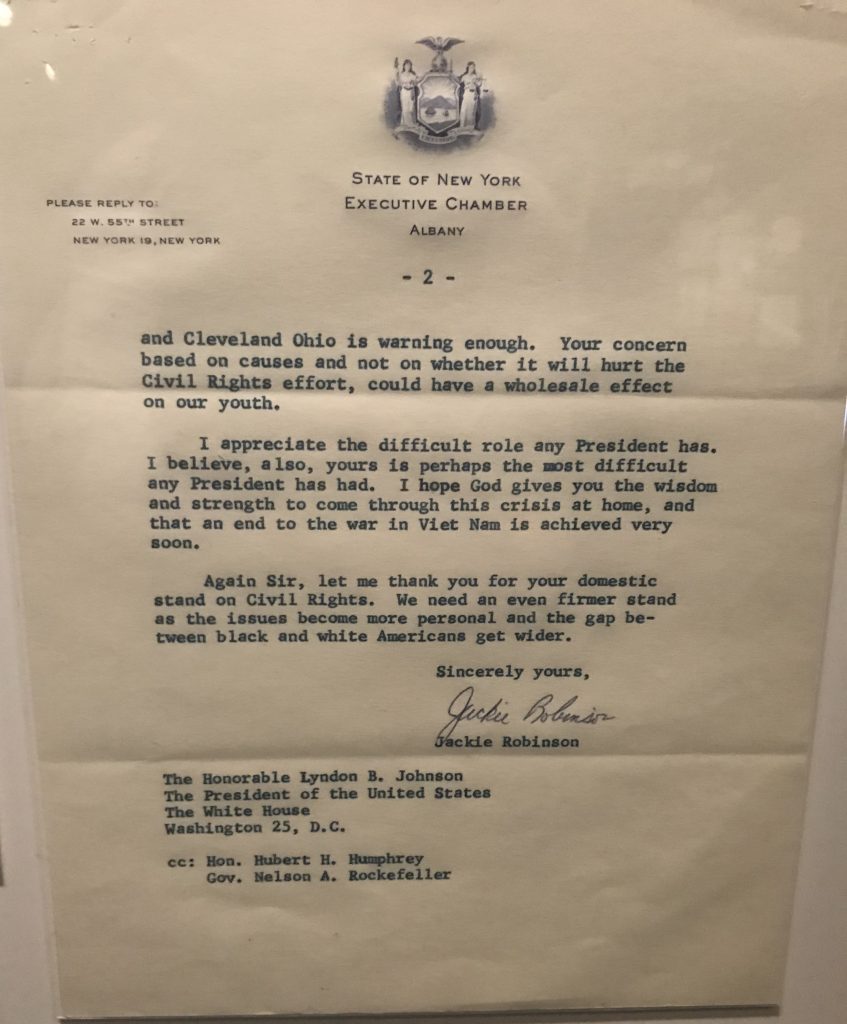

Robinson committed much of his time in retirement to activism, working with the NAACP, encouraging other black athletes, and communicating with several politicians. “Get in the Game” features letters and telegrams from Robinson to Presidents Eisenhower, Kennedy, Johnson, and Nixon. The letters show Robinson’s concern that Civil Rights remain a presidential priority throughout changes in regimes, as well as his concerns about the morality and risks regarding the Vietnam War.

Robinson implored Eisenhower to do more for African Americans, writing, “I was sitting in the audience at the Summit Meeting of Negro Leaders yesterday when you said we must have patience. On hearing you say this, I felt like standing up and saying, “Oh no! Not again!” I respectfully remind you sir, that we have been the most patient of all people. When you said we must have self-respect, I wondered how we could have self-respect and remain patient considering the treatment accorded us through the years.”

Robinson also engaged Presidents regarding black liberation in Africa and Dr. King’s anti-war stance. He wrote to President Kennedy, “With the new emerging African nations, Negro Americans must assert themselves more, not for what we can get as individuals, but for the good of the Negro masses. I thank you for what you have done so far, but it is not how much has been done but how much more there is to do. I would like to be patient Mr. President, but patience has caused us years in our struggle for human dignity.”

When Dr. King protested the Vietnam war in 1967, Robinson wrote to President Johnson, “I do feel you must make it infinitely clear, that regardless of who demonstrates, that your position will not change toward the rights of all people; that you will continue to press for justice for all Americans and that a strong stand now will have great effect upon young Negro Americans who could resort to violence unless they are reassured.”

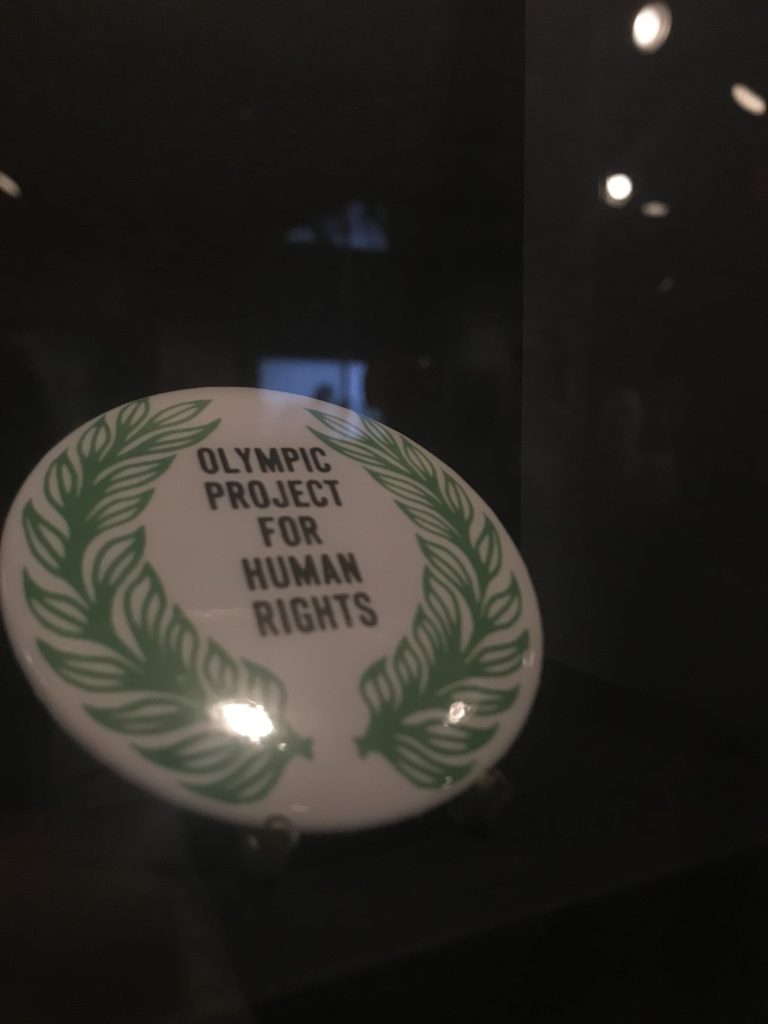

Another strength of the exhibition is the number of items on loan or gifted from the Dr. Harry Edwards Archives at the San Jose State University Institute for the Study of Sport, Society and Social Change. Dr. Edwards led the Olympic Project for Human Rights (OPHR), the group that organized the boycott of the 1968 Mexico City Olympic Games, and continues to work with athletes, including Colin Kaepernick. The exhibition focuses not only on Tommie Smith and John Carlos’s iconic anthem protest and its 50th anniversary, but also the support, solidarity, and demands of the OPHR.

Mere days before his assassination, Dr. King met with Dr. Edwards and endorsed the athletes’ “courage and determination to make it clear that they will not participate in the 1968 Olympics until something is done about these terrible evils and injustices.” Five members of the Harvard Rowing team, due to compete in the Games, appeared with Dr. Edwards to officially state, “It is their criticisms of society which we here support.” Black students at Harvard Law also stated that they supported the athletes’ “willingness to sacrifice the fruits of your labor for the achievement of the goals of Black Americans.”

Though the International Olympic Committee (IOC) met one of the demands of the OPHR, that South Africa and Rhodesia be uninvited to the games, and the boycott was called off, Lew Alcindor (Kareem Abdul-Jabbar) and other basketball players maintained their stance and did not compete at the games.

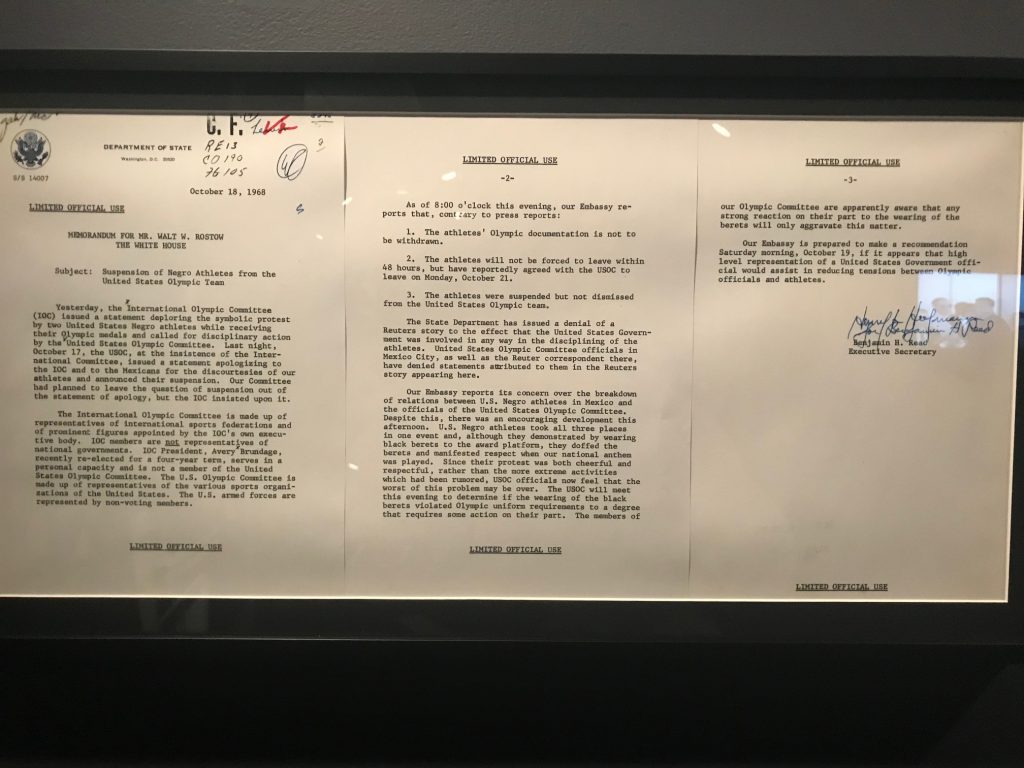

Even for those athletes who did compete, the spirit of the OPHR continued, breeding both solidarity and backlash. An OPHR button is included in the exhibition, like the ones worn by Smith, Carlos, and the Australian runner Peter Norman who won the silver medal alongside Smith’s gold and Carlos’s bronze. Displayed adjacent to the button is a State Department memo concerned with what to do about the demands from the IOC to remove Smith and Carlos from the Olympic Village, though the athletes ended up leaving on their own, returning to backlash from the press and the public.

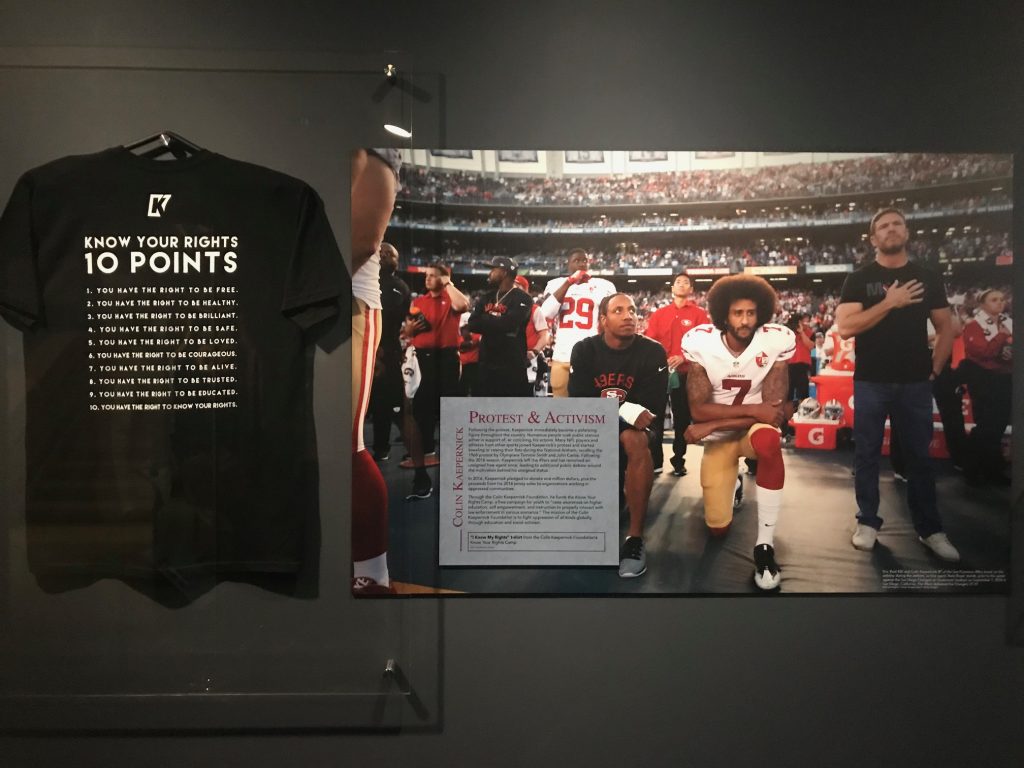

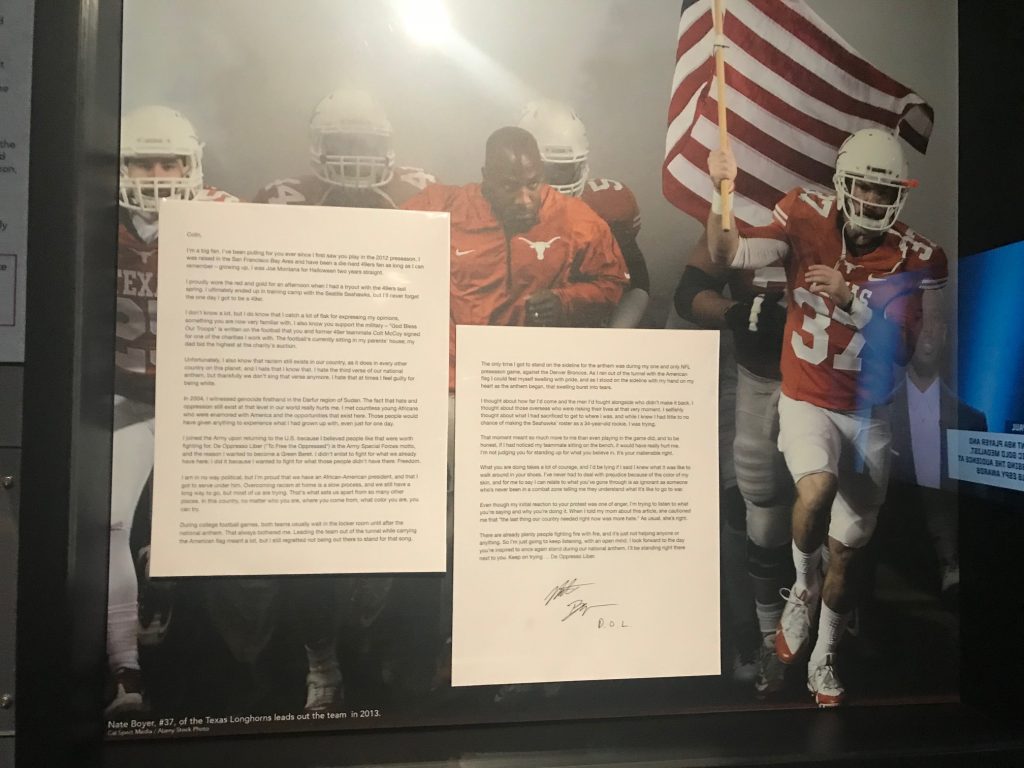

The exhibition closes with Kaepernick and notes his connection to the 1968 Olympics. A unique strength of the materials is the inclusion of University of Texas at Austin alumnus Nate Boyer, who worked with Kaepernick to attempt to bridge the divide between his protest and American servicemen and women and their families.

A notable curatorial decision that mutes the political nature of the exhibit and fails to connect Jackie Robinson, the 1968 games, and Colin Kaepernick, is the omission of Jackie Robinson’s autobiography I Never Had it Made (1972). This is a common missed connection in the anthem protest legacy. Calling upon Frederick Douglass’s 1852 speech, “What to a Slave is the Fourth of July?”, the introduction to Robinson’s book recalls game one of the 1947 World Series, Robinson’s rookie year. He writes, “The band struck up the national anthem. The flag billowed in the wind. it [sic] should have been a glorious moment for me as the stirring words of the national anthem poured from the stands. Perhaps it was, but then again perhaps the anthem could be called the theme song for a drama called The Noble Experiment . . . As I write this twenty years later, I cannot stand and sing the anthem. I cannot salute the flag; I know that I am a black man in a white world. In 1972, in 1947, at my birth in 1919, I know that I never had it made.”

Though the decision to omit the autobiography is an easily defendable one—the focus on Robinson is his breaking the color barrier and his correspondence with Presidents—it stands out because of the inclusion of other athletes’ autobiographies and provocative statements. Perhaps more accessible due to the museum’s possession of an inscribed copy owned by LBJ, Bill Russell’s book Go Up For Glory (1966) is included, along with details of his delivery of Muhammad Ali’s refusal to serve in the military.

As visitors exit “Get in the Game,” the last item they see is the block quote, “If there is no struggle there is no progress,” from Frederick Douglass. Knowing what we do about Robinson, Smith and Carlos, and Kaepernick, it is also worth considering a quote from Douglass’s “Fourth of July” speech:

“The Fourth [of] July is yours, not mine. You may rejoice. I must mourn. To drag a man in fetters into the grand illuminated temple of liberty, and call upon him to join you in joyous anthems, were inhuman mockery and sacrilegious irony.”

More like this:

Unsportsmanlike Conduct: College Football and the Politics of Rape

Muhammad Ali Helped Make Black Power into a Global Brand

Remembering Willie ‘El Diablo’ Wells and Baseball’s Negro Leagues