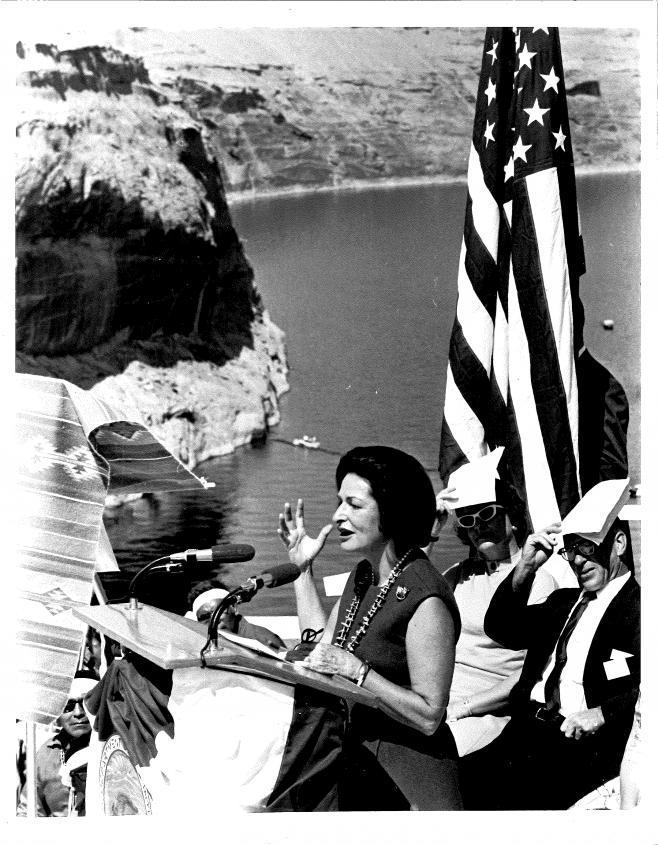

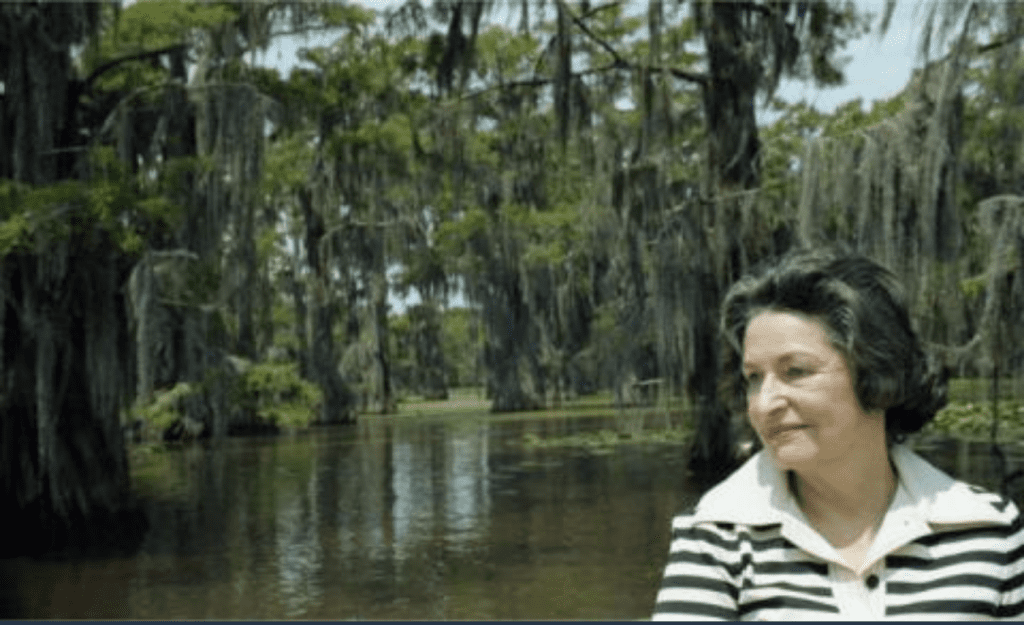

This Associated Press photograph was taken in 1966 to accompany an article by Frances Lewine about Lady Bird Johnson’s beautification project, entitled, “Her Program’s Progress.”

“Mrs. Lyndon Johnson has begun a national movement to eradicate blighted and ugly scenery from America, feeling ‘ugliness is an eroding force on the people of the land.’ On visits to small towns, large cities, national parks and points of scenic and historic interest, she related such visits to the benefits of natural beauty. She has been instrumental in legislation and donations to improve, clean up or renovate national eyesores everywhere. Here, before a backdrop of Lake Powell, Mrs. Lyndon Johnson speaks at dedication ceremonies of the Glen Canyon Dam near Page, Arizona, in late September 1966.”

When Lady Bird took the podium, as one of a host of national and local politicians, she pointed out that the region surrounding the dam “consists of eons of time laid bare – on stone pages and in the treasure troves of Indian myths and artifacts” that would make the resulting Lake Powell “a magnet for tourists.” Evoking the genius of technology, the conservation of water, and the spirituality of nature, she remarked, “To me, the appealing genius of conservation is that it combines the energetic feats of technology – like this dam – with the gentle humility that leaves some corners of the earth untouched – alone – free of technology – to be a spiritual touchstone and a recreation asset.”

Only a decade earlier, the area that Lake Powell flooded had been a vast, arid desert, peppered with ancient American Indian cliff dwellings and majestic rock structures, like Rainbow Bridge. The resulting reservoir was impressive given that it filled up a network of side, slot, and crater canyons measuring more than 150 miles long and with a shoreline longer than the east coast of the United States. The dam — a barrier of five million cubic yards of reinforced concrete (more concrete than was used in Hoover Dam) — was hailed as one the “the engineering wonders of the world” by the Bureau of Reclamation as well as local newspapers, and state and local officials in both Arizona and Utah. It was honored as “the outstanding engineering project” by the American Society of Civil Engineers.

Yet, among environmentalists it was (and is) considered one of the nation’s most controversial projects. Flooding the canyon disrupted the free flow of the Colorado River, destroyed the original natural beauty of the site, and made dozens of plant and wildlife species extinct.

Clearly, beautification was in the eye of the beholder. For Lady Bird Johnson, as well as many other Americans, technology did not necessarily ruin nature. Later on this leg of her 1966 Beautification tour, she also paid a brief visit to San Ildefonso Indian Pueblo, dedicating a highway and a park and planting seedlings. All of this earned her the nickname: “Our First Lady of National Beautification” from the New York News on November 13, 1966.

Often when thinking about Lady Bird Johnson’s Beautification Program, we overlook the ways she celebrated technology as much as nature — especially if it aided people’s access to nature or natural resources.

For more, see Erika Bsumek’s book: The Foundations of Glen Canyon Dam: Infrastructures of Dispossession on the Colorado Plateau (University of Texas Press, 2023)

The text of the speech may be found: Lady Bird Johnson, “Glen Canyon Dam Dedication Ceremony,” item display 75982, Cline Library, Northern Arizona University.

Photograph: from the author’s private collection.

Another great aunt, the prominent suffragist, Birdie Johnson, became the first Democratic national committeewoman from Texas. As she exhorted women to organize to make their influence felt at the polls, she declared that it was “our first step” in the exercise of “direct political power.” No wonder Liz believed that she had inherited her feminist genes.

Another great aunt, the prominent suffragist, Birdie Johnson, became the first Democratic national committeewoman from Texas. As she exhorted women to organize to make their influence felt at the polls, she declared that it was “our first step” in the exercise of “direct political power.” No wonder Liz believed that she had inherited her feminist genes. It also instilled a love of Texas history and a respect for its historians, which is why

It also instilled a love of Texas history and a respect for its historians, which is why  When Liz made a courtesy call on her congressman, she discovered that his wife was running the office while he was overseas. It was that visit that introduced Liz Carpenter to

When Liz made a courtesy call on her congressman, she discovered that his wife was running the office while he was overseas. It was that visit that introduced Liz Carpenter to

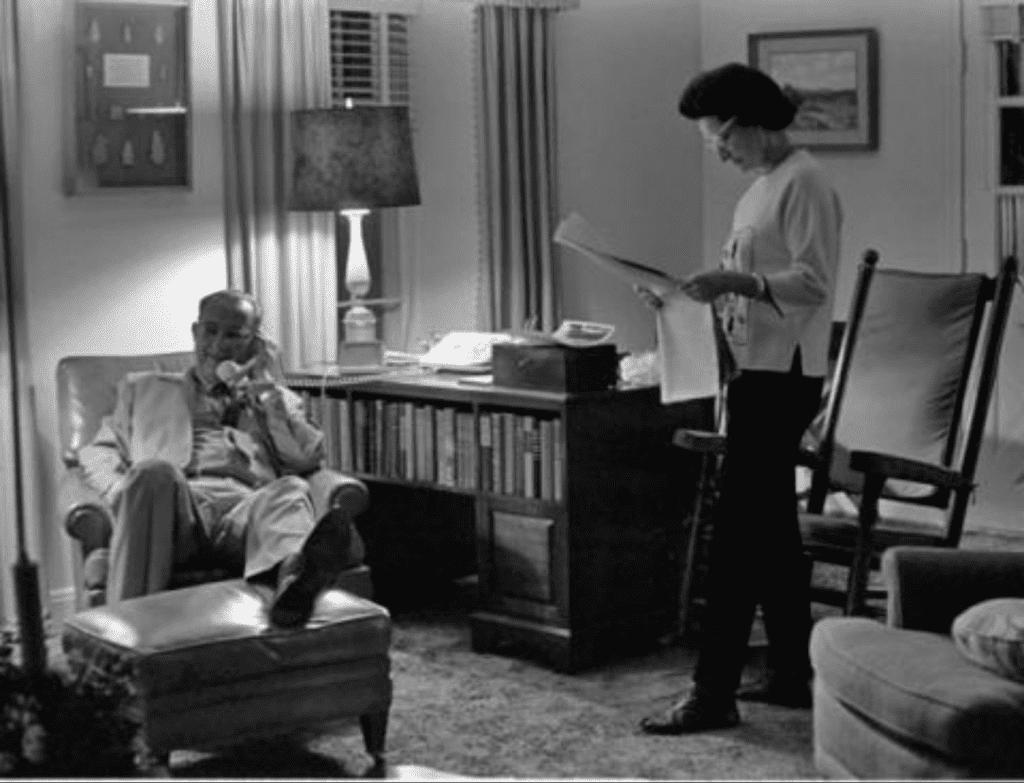

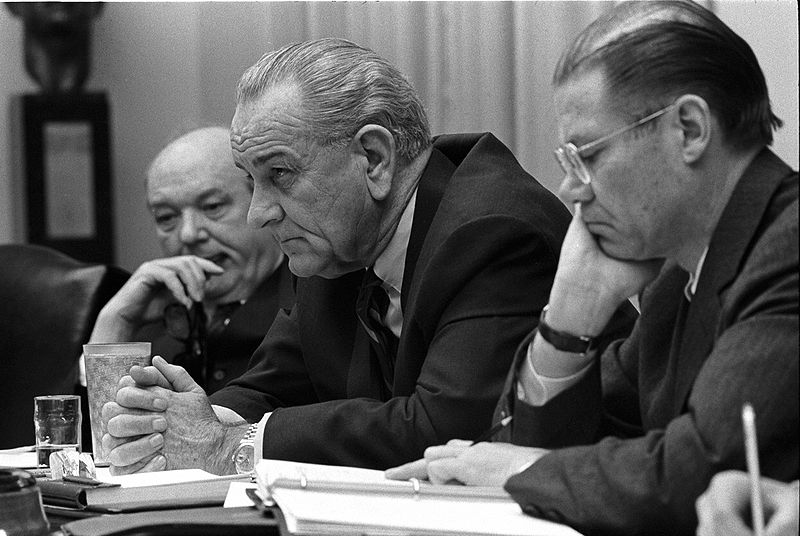

Clark and Libbie Moody Thompson entertained Texans so often that their elegant home became known as the Texas Embassy. And on countless Sundays, the four Carpenters–Liz, Les, Scott, and Christy—would spend the afternoons, at the Johnson home with Speaker Rayburn, other members of Texas congressional delegation, and the Texas press and their families. The topic of discussion was always politics. What an extraordinary postgraduate education these afternoons must have been!

Clark and Libbie Moody Thompson entertained Texans so often that their elegant home became known as the Texas Embassy. And on countless Sundays, the four Carpenters–Liz, Les, Scott, and Christy—would spend the afternoons, at the Johnson home with Speaker Rayburn, other members of Texas congressional delegation, and the Texas press and their families. The topic of discussion was always politics. What an extraordinary postgraduate education these afternoons must have been!