Fifty years ago Soviet tanks rolled through the streets of Prague. Soviet and Warsaw Pact forces entered Czechoslovakia on August 20, 1968, and within two days occupied the entire country. The Soviet Union and its allies had decided that the reformist experiment, “socialism with a human face,” in communist Czechoslovakia was too dangerous, and might provoke a wave of democratization across the Eastern Bloc. When the tanks came in August 1968, thousands of Czechoslovaks were abroad in western Europe and the U.S., taking advantage of recent visa liberalizations to go on vacation and do business. Once it became clear in the days after the invasion that the “normalized” regime would return to the old days of communist repression and isolation, many decided not to go home, instead opting to seek asylum where they were. Before long the U.S. and its allies were beset by refugees from Czechoslovakia, fleeing the imposition of what would become one of the most brutal, authoritarian, and isolationist regimes in the Communist Bloc. How did the U.S. and its allies respond to this wave of political and economic refugees?

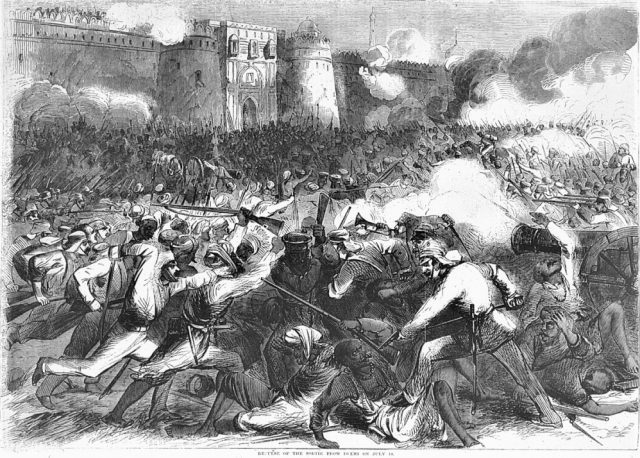

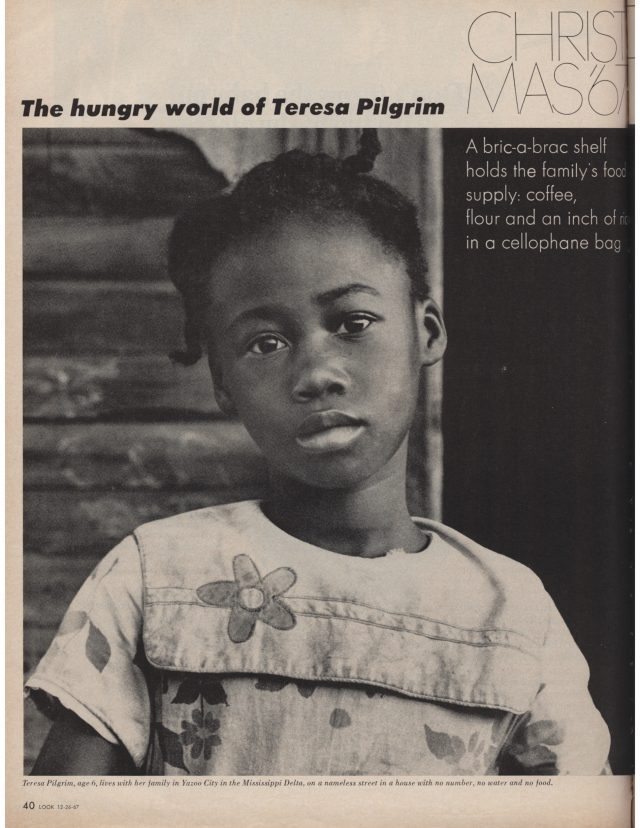

Men carrying national flag while a Soviet tank burns during the Prague Spring. (via Wikipedia)

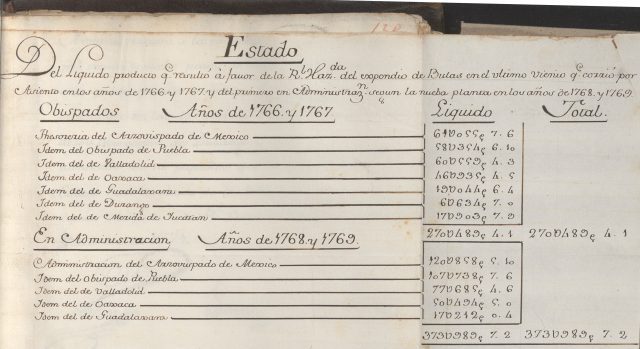

This story begins with a telegram sent from the U.S. mission in Geneva, Switzerland, to Washington D.C. sometime in August after the invasion. The telegram notes the presence of “several thousand” Czechoslovak citizens abroad. It then requests instructions from D.C. on how to handle the situation, as most of these citizens are expected to seek asylum. It also recommends that the U.S. commit up to $100,000, nearly three quarters of a million dollars in today’s money, in order to “insure needs [of] asylum seekers [are] adequately met.” The main concern of the message was not to keep people out or send them back to Czechoslovakia, but to meet the needs of the refugees, presumably granting as many of them asylum as possible.

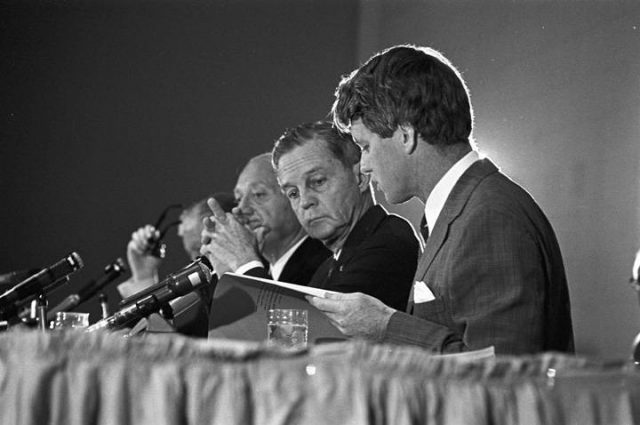

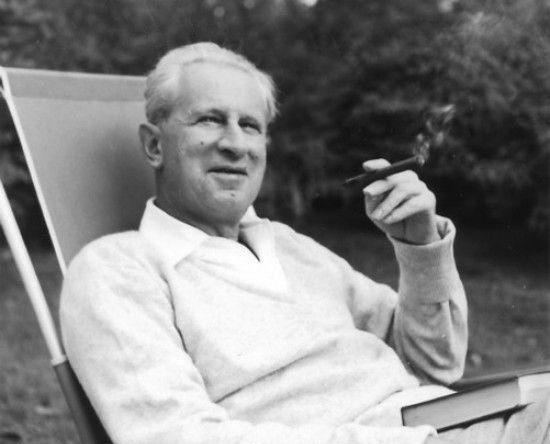

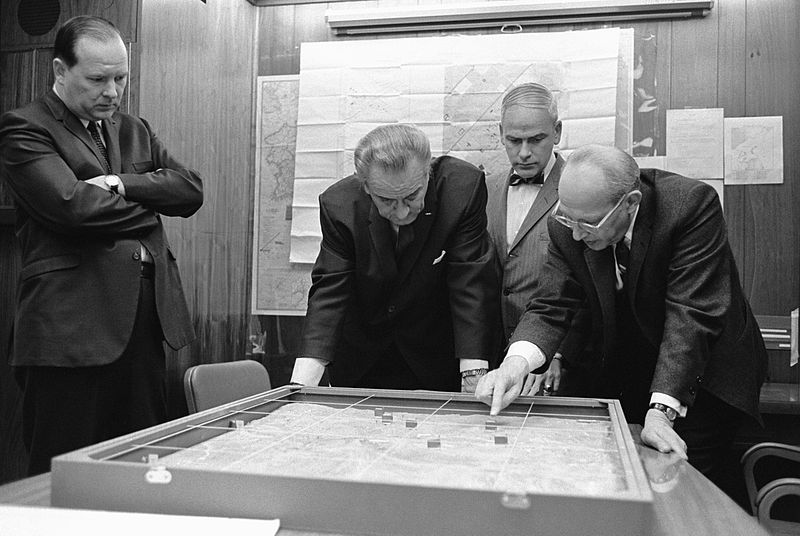

Walt Rostow (vie Wikipedia)

A couple of weeks later at the start of September, then President Lyndon Baines Johnson exchanged a flurry of memos with his advisers, in particular Walt Whitman Rostow. A staunch anti-communist and right-wing economist, Rostow advised the president, in a memo dated September 4 to allocate $20 million (about $145 million adjusted for inflation) to pay the costs of “reception, interim care and maintenance, resettlement processing, transportation, [and] integration.” He also notes that the refugees will be shared out among American allies, including Canada, Australia, the United Kingdom, while Germany and Austria will take the majority, indicating that there was significant international cooperation on this issue. Most interestingly, Rostow appeals to “our national heritage, our traditional humanitarian role, and our foreign policy interests” to make the case for accepting and resettling refugees. This rhetoric obviously stands in stark contrast to contemporary attitudes and policies in many of these same governments. Rostow also prepared a draft statement for the President that would have had the President saying “I declare that our doors are open as they always are to those who seek freedom.”

However it seems that this statement was only the first draft, and subsequent drafts toned down the “open door” message substantially while still stating that the U.S. government will still make provisions for the “orderly entry, in accordance with our immigration laws, of those Czechoslovak refugees who desire to come to the United States.” Nevertheless, the administration confirmed that they would spend money to process and resettle Czechoslovak refugees.

A Photo of Czech Children in front of a Bandstand in the United States (via Immigrationtous.net)

While the current administration has adopted a violently combative stance in reaction to migration into the United States (including not only policies implemented at the U.S.-Mexico border, but also the blanket ban on travelers from several predominately Muslim countries), fifty years ago the U.S. government was planning to spend a significant amount of government funding to process and accommodate refugees from Soviet-style communism. The President’s advisors explicitly argued for this policy not just on cynical, “Cold Warrior” grounds, but also out of a sense of American history and tradition. Johnson and his advisors saw this policy as the American thing to do to welcome refugees fleeing violence, at least in the context of the Cold War in Soviet-dominated Europe. The contrast between these two events highlights how important contemporary politics are in shaping responses to humanitarian crises. During the Cold War, the U.S. and its allies was generally willing to welcome anyone fleeing from communist regimes throughout Eurasia. Finally, it also highlights the fact that migrants and refugees from some parts of the world are treated with greater sympathy by the U.S. government than people from others.

Sources:

The Prague Spring Archive (at the LBJ Library and Museum)

Box 180, Folder 2:

#39 “Memo for President Johnson Regarding Czech Refugees”

#70 “Telegram Regarding Czech Refugees and Border Closings”

#19 “White House Memo for Rostow Regarding Czech Refugees”

#25 “Statement of President Johnson on the Admission of Czech Refugees to the United States”

Other Articles You Might Like:

Texas Czech Culinary Traditions

Fifty Years since the Prague Spring

Searching for Armenian Children in Turkey