Inspired by a never-finished ceremonial cup of coffee in Ethiopia and a Jules Michelet quote attributing the Enlightenment to the advent of coffee, author Stewart Lee Allen dives head-first into a voyage across the world to trace the path coffee took out of Africa. In The Devil’s Cup: A History of the World According to Coffee, Allen weaves the history of coffee in between his eccentric tales of travel. A self-proclaimed “addict” himself, Allen argues that the coffee bean’s integration into our daily lives has been central to the flourishing of human civilization, from intellectual innovations in the Arabic world to the political revolutions of the West.

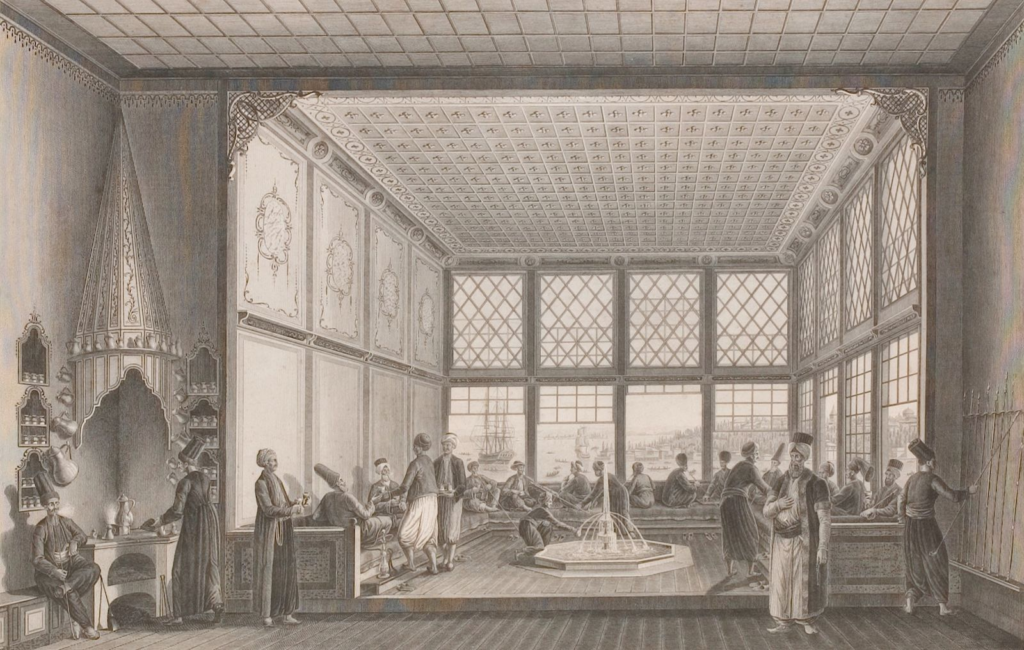

Allen focuses on the role of coffee in culture, politics, spirituality, and trade. Coffee’s link to spirituality is explored throughout the first half of the book. The journey begins in Harrar, Ethiopia, where it is believed that the cultivation of the aromatic Coffea Arabica species began. Allen attends a traditional ritual from the Oromo tribe – an exorcism in which coffee beans are roasted, chewed, and then brewed to release the power of the priest. In what follows, Allen attempts to visit the alleged home of al-Shadhili in al-Makkha (Yemen), the Muslim idol who is rumored to have invented brewing coffee beans for drinking in 1200 C.E. Allen stresses how a group of traveling Islamic orders called Sufis incorporated coffee into their spiritual practices and contributed to its spread beyond North Africa. In Turkey, Allen traces the roots of contemporary coffee consumption habits and takes the story up to coffee’s introduction to Europe.

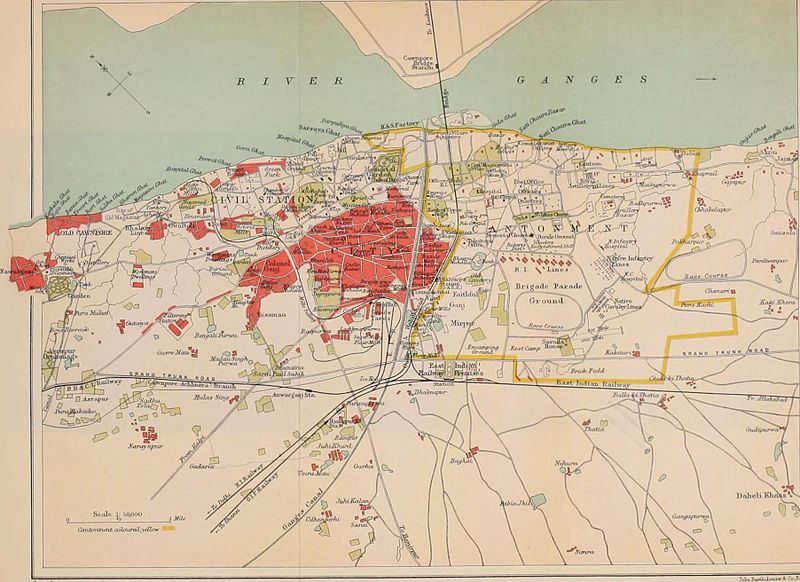

Source: Wikimedia Commons

Allen’s primary argument rests upon the social and historical impact of the coffee shop to prove his thesis. Previously centered around drinking in taverns, European society lacked a common space for sober socialization. A drunk mass, consuming beer as though it was water, led to a less efficient, intellectual, and healthy population. Coffeehouses became multi-functional public spaces that facilitated a multitude of historical moments. They were the original meeting spots of choice for business powerhouses like Lloyd’s of London and the East India Company. As well, these cafés served as spaces for intellectual dialogue, where scientists like Isaac Newton or philosophers like Jean-Jacques Rousseau were known to frequent. Allen even states that in being a site for political organizing, the cafés of Paris were central to the French Revolution. As he himself admits, some of Allen’s claims are bold. For example, he suggests that this stimulant pushed the Ottoman empire to success, created Great Britain’s drive for dominance, contributed to Napoleon’s fall, and even helped the Sons of Liberty attain independence from the British.

After Allen’s long discussion of Europe, we find the author distracted from his “history of the world according to coffee” and focusing more on storytelling. He continues his narration of Gabriel De Clieu’s fabled introduction of the coffee bean to the New World until he arrives in Brazil. The focus here is on the link between coffee and the horrors of Brazilian slavery. In wondering if the slave trade brought with it coffee’s spiritual origins in the Zar cults of eastern Africa, he finds himself participating in an Afro-Brazilian ritual where coffee beans are left as an offering to summon a spirit named Preto Velho.

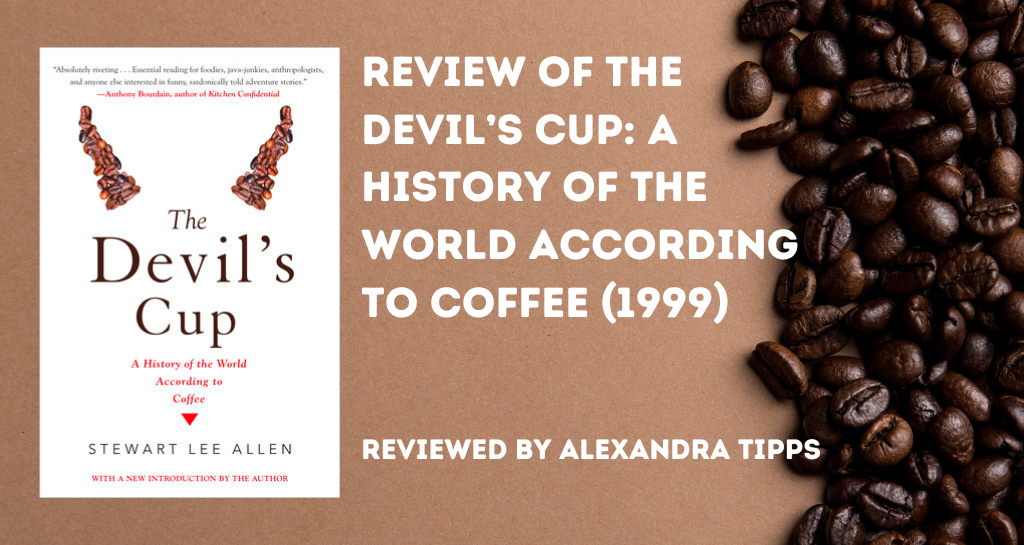

The final stretch of the author’s trek takes him to the United States. Following Route 66, Allen seeks the quintessential cup of coffee, i.e., a foul but “soulful” cup of drip, ever flowing thanks to the attentiveness of a kind all-American waitress. After finding himself at the mercy of several Tennessee cops and countless stops at roadside chain restaurants and diners, he heads home to Los Angeles. The book fades out in ephedrine and caffeine-induced haze, where the author gives his final ruminations on the substance: “…Each age had used the bean according to its understanding of reality…We citizens of the brave new world, who worship efficiency and speed, are just turning it into a high, another way to go a little faster, get there a bit quicker and feel a little better. Only there’s nowhere left to go” (p. 223).

Source: Library of Congress, Prints & Photographs Division, photograph by John Margolies, call number LC-MA05- 7312

Allen’s book is fast-paced, entertaining, and easy to read. But this assessment comes with significant reservations. While there is certainly truth to many of these claims, I suspect that the author has overstated the role of coffee. Some of his work seemed to shade into fiction, a problem for a book that claims to be factual. There was a minimal inclusion of dates and citations, which made it more difficult for me to take what he was saying seriously. The timeline felt fuzzy, and occasionally, facts seemed poorly researched. For example, Allen argues that coffee’s 13th-century arrival in al-Makkha not only aided the intellectual advancements of the Islamic world but allowed their civilization to “flourish beyond all others”. Many historians consider the Islamic Golden Age to have occurred from the 8th to the 13th centuries.[1] Coffee reached this region during a period of decline for some of these older empires, and the flourishing of the Ottoman Empire that Allen points to was yet to come for a couple of centuries.[2]

The book often reads more like a travelogue than historical literature. Many of his side discussions felt aimless, almost like reading someone’s inner monologue. Allen’s sardonic tone was humorous at times but occasionally felt obnoxious. His characterization of some of the Middle Eastern and Indian people he met during his journey seemed to evoke Orientalist tropes. The author’s insensitivity may be attributed to the age of the book, which is now twenty-five years old, but it makes the work feel dated. Some descriptions were deeply problematic, for instance, Allen’s description of India: “Most people do not associate India with coffee. Disorganized, dirty, undereducated, lazy, muddled, poor, and run-down – not to mention superstitious – it is clearly a nation of tea drinkers” (p. 76).

Despite these criticisms, The Devil’s Cup is an interesting and accessible read for those looking to learn more about the origins of one of the world’s most beloved beverages. The sections focused on presenting historical information and analysis were well-written and drew my attention. There were a handful of lines that struck me for their beauty. Allen knows how to paint a scene, and his colorful descriptions of coffee often made me crave a cup. Here’s just one example: “It proved to be the first all-American joe we’d found – black, tarry, and powerful, rich with half-and-half, cascading in waves from the waitress’ Pyrex coffeepot and into our mugs, breaking over us, washing through our veins like rocket fuel. It was awful and terrifying beyond compare” (p. 220). While the book has flaws, Allen’s story remains a unique, light-hearted whirlwind of a read. And if you love coffee, The Devil’s Cup will likely make you cherish your morning cup even more.

Alexandra Tipps is a senior in the College of Liberal Arts, currently working toward her B.A. in History and Sociology. She hopes to pursue a Ph.D. in History with a focus on modern Latin America.

[1] Steve Tamari, 2009. “Between the ‘Golden Age’ and the Renaissance: Islamic Higher Education in Eighteenth-Century Damascus.” In Trajectories of Education in the Islamic World, edited by Osama Abi-Mershed (Routledge: 2009): 36

[2] Şahin, Kaya. Empire and Power in the Reign of Süleyman: Narrating the Sixteenth-Century Ottoman World / Kaya Şahin, Indiana University (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2013), 7-8

The views and opinions expressed in this article or video are those of the individual author(s) or presenter(s) and do not necessarily reflect the policy or views of the editors at Not Even Past, the UT Department of History, the University of Texas at Austin, or the UT System Board of Regents. Not Even Past is an online public history magazine rather than a peer-reviewed academic journal. While we make efforts to ensure that factual information in articles was obtained from reliable sources, Not Even Past is not responsible for any errors or omissions.