“Colonial Latin America Through Objects” is a class taught by Prof. Jorge Cañizares that offers a view of a region’s past by exploring material remains: currencies, playing cards, musical scores, water mills, comets, relics, mummies, coded messages, to name only a few of the 50 objects studied. The class introduces students to a region from unusual angles that upset deeply seeded assumptions about Hispanics.

The students are required to produce two online museum exhibits. The five best exhibits for the mid–term are sampled here. These five exhibits address unusual aspects of colonial Latin America through their material culture. Click on links to see full exhibits (and credits for images).

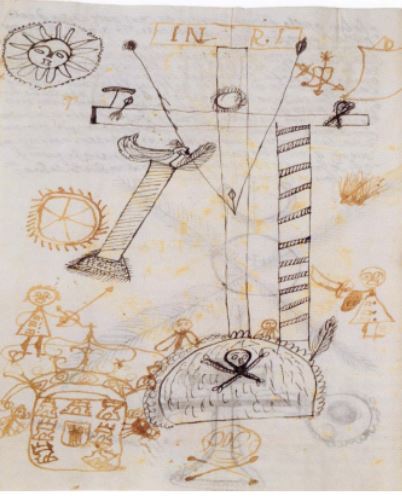

The history of conquest as described in sixteenth-century indigenous codices by Tymon Sloan

Bernadino De Sahagun,

Illustration of the Mirror-Faced Bird, La Historia Universal De Las Cosas De Nueva Espana,1577

Medicea Laurenziana Library, Florence, Italy

Cranial Deformity and Identity by Aaron Quintanilla

Native Drinking Cups of the New World by Riley Reynolds

Syncretism and Marian Representations by Lily Folkerts

Las Bolsas de Mandingo: Deconstructing Misconceptions of Traditional African Religions in the Luso-Atlantic World, by Maryam Ogunbiyi

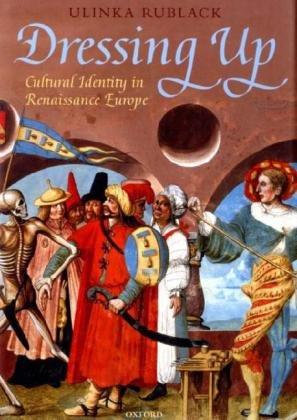

Schwarz’s life may well have been forgotten if he had not taken the unusual step of memorializing it in an extraordinary manuscript. In his Klaidungsbüchlein, or “Book of Clothes,” Schwarz commissioned one hundred and thirty seven vivid watercolor paintings depicting the clothes he wore at each stage of his life, from his “first dress in the world” as a days-old infant to the somber robes of mourning he wore as a world-weary man of sixty-seven.

Schwarz’s life may well have been forgotten if he had not taken the unusual step of memorializing it in an extraordinary manuscript. In his Klaidungsbüchlein, or “Book of Clothes,” Schwarz commissioned one hundred and thirty seven vivid watercolor paintings depicting the clothes he wore at each stage of his life, from his “first dress in the world” as a days-old infant to the somber robes of mourning he wore as a world-weary man of sixty-seven.

Like Smith,

Like Smith,