Introduction to Memories of War by Lucero Estrella, Assistant Professor of Ethnic Studies at Lawrence University

When developing my syllabus for ETST 110: Introduction to Ethnic Studies, I thought of ways to have students at Lawrence University engage with the themes of race, ethnicity, borders, gender, indigeneity, and migration beyond the United States. Each week, we discussed themes such as settler colonialism, racialization, criminalization, and resistance and how these appeared across various temporalities and global geographies.

For our week on resistance and exclusion during the mid-twentieth century, I decided to have my students read my NEP piece “Memories of War: Japanese Borderlands Experiences during WWII,” alongside Karen M. Inouye’s article “No Simple History: Nikkei Incarceration on Indigenous Lands.”[1] My goal was to have students engage with alternative histories of Japanese internment that they might not have encountered in the past. While my NEP piece approaches Japanese incarceration and family separation through a hemispheric lens and discusses Japanese wartime experiences on both sides of the Texas-Mexico border, Inouye’s work centers Nikkei women’s narratives of incarceration on Indigenous land to highlight the interconnections between racial capitalism, settler colonialism, and wartime incarceration. Both works discuss the importance of memory in historical studies of the wartime period as a way of uncovering the continuing legacies of state violence.

For my class, students were expected to write one weekly, in-class free writing exercise based on a few guiding questions. During the week we read both works, students were required to tackle one or more of the following questions: How do Estrella and/or Inouye use memory in their works? Who do these memories belong to? What new perspectives and possibilities emerge from the use of memory as a historical source?

The four reflections below are from four Lawrence University students who took my Fall 2024 term Introduction to Ethnic Studies course: Tahlia Moe, Niranjana Mittal, Nicholas Lubin, and Riya Jehangir Stebleton. Their short preces include reflections on some themes and methodologies that structured our class discussions for the term, such as relational race, racial capitalism, settler colonialism, and incarceration.

Student Reflections

Tahlia Moe

Memory serves as the gateway to a hidden archive. Employing memory as a historical source unearths relations, stories, intimacies, and experiences that traditional historical methods often overlook. “Memories of War: Japanese Borderlands Experiences during WWII” by Estrella and “No Simple History: Nikkei Incarceration on Indigenous Lands” by Inouye explore the hidden archive as they prioritize memories as primary sources. Estrella highlights memories from Japanese families and activists in the U.S. and Mexico to display the legacies of violence and anti-Asian exclusion on both sides of the U.S.-Mexico border. Meanwhile, Inouye writes about Nikkei incarceration on Indigenous lands in Arizona, featuring memories from Japanese women who were imprisoned as children in Poston. The memories of these women reveal legacies of racial capitalism and settler colonialism that are downplayed, erased, or otherwise not found in the archives. Their memories reveal interactions between the Japanese prisoners and the Indigenous people as they created their own economies and forms of resistance. A relational race approach becomes significant to understanding the interactions between the groups and the effects of state-sponsored violence and settler-colonialist ideologies and policies. Compiling these memories helps form a fuller, more empathetic picture that cares about and honors subjects of violent histories. Emerging perspectives from people involved thus introduce the personal perspective and intimate value, combatting traditional historical methods.

Niranjana Mittal

Estrella’s piece titled “Memories of War: Japanese Borderlands Experiences during WWII,” explores lived experiences from the Texas-Mexico borderlands through the lens of memory. By using oral histories and personal recollections, Estrella centers the humanity of these historical events, presenting an intimate narrative that contrasts with more traditional archival sources. Memory in her work becomes a vital tool for uncovering some overlooked aspects of history. Estrella’s use of memory is particularly powerful in reconstructing histories that lack extensive documentation or have been marginalized in mainstream narratives.

The memories she draws upon belong to individuals who lived through the upheaval of war. These are ordinary people whose voices are often absent from official records but whose experiences illuminate the complexities of war beyond its grand strategies and political machinations. For example, recollections of displacement and resource scarcity challenge the monolithic view of Japan as solely a wartime aggressor, adding nuance to our understanding of suffering in Japanese Mexican communities during the war. Estrella uncovers the brutality of imperial policies and how individuals navigated and survived these oppressive systems.

One of the most significant effects of Estrella incorporating these memories is how it opens up new perspectives on history. Memory, unlike official records, is subjective and malleable, shaped by individual experiences and the passage of time. This fluidity allows us to reveal dimensions of history that might otherwise remain hidden. For instance, memories often preserve emotional truths and everyday experiences that are absent in traditional state sources. They bring to light stories of resilience, survival, and moral ambiguity that challenge simplistic narratives of victimhood or villainy. Estrella shows how the memories of those at the margins, such as borderland communities, challenge nationalistic accounts that erase the interconnected and often contradictory realities of the war.

Moreover, memory as a historical source opens up possibilities for reconciliation and healing. By including voices that have been silenced or ignored, Estrella’s work fosters a more inclusive understanding of history that acknowledges shared pain and loss across national and cultural boundaries. This approach humanizes history and highlights how memory itself is contested and politicized as individuals and communities negotiate their relationship with the past.

Ultimately, Estrella demonstrates that memory is not just a supplement to traditional historical sources but a vital means of understanding the complexities of human experiences. By foregrounding memory, she shifts the focus from the macro-level forces of war to the lived experiences of individuals – offering a richer, more empathetic perspective on the past.

Nicholas Lubin

In both Estrella’s and Inouye’s works, memory functions as a significant tool for recovery from the deterioration of Native American and immigrant narratives. Due to the United States’ history of isolation and displacement, many families are left with gaps in their history. However, memory functions to fill this gap. Although instances of displacement and isolation are not always documented, memory and oral histories help fill this gap. Memory in Inouye’s piece serves as a connector for the experiences of Japanese Americans who were subjected to incarceration following Executive Order 9066 and those of Native Americans who were displaced from their lands.

Inouye illustrates this overlap through the locations of campsites on Indigenous reservations mirroring the state-imposed limits and borders for the “allowed” spaces for Native peoples. Despite the differing circumstances of the two groups, the process of isolation and extermination is one and the same. Both works feature minority groups that were forcibly relocated because of the unsettling habits that hegemonic powers hold onto, such as settler colonialism and xenophobia. In Estrella’s work, she details this, showing the reader the widespread cross-border relocation of Japanese nationals following the bombing of Pearl Harbor. Families across the Americas were torn apart, and many never returned to their homes, causing this impactful moment to fall under the radar. Estrella’s inclusion of oral history and memories of a Japanese Mexican family illustrates how the attempt to silence these voices with equivocation can be combated by preserving the narratives and memories of those who experienced violence and displacement during the wartime period.

Riya Jehangir Stebleton

The erasure of immigrant and Indigenous stories in the United States is a constant theme within hegemonic white narratives. Many families are unable to retrace the steps of their ancestors due to the history of exclusion, internment, and forced separation of ethnic groups. In the works of Estrella’s “Memories of War” & Inouye’s “No Simple History,” memory and empathy are used as powerful mechanisms to bridge historical gaps in the lives of both Japanese and Indigenous communities in the Americas. Although these communities endured different forms of injustice, an overarching system of racism in incarceration and exclusion can be seen through a relational race lens.

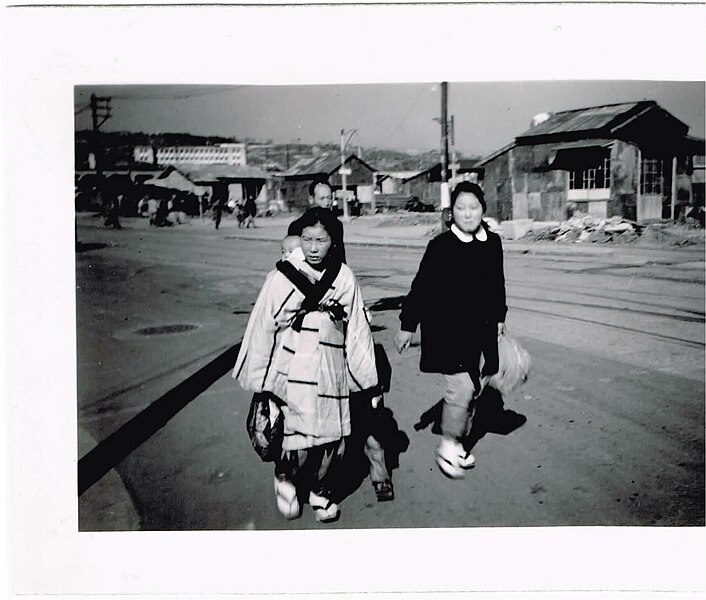

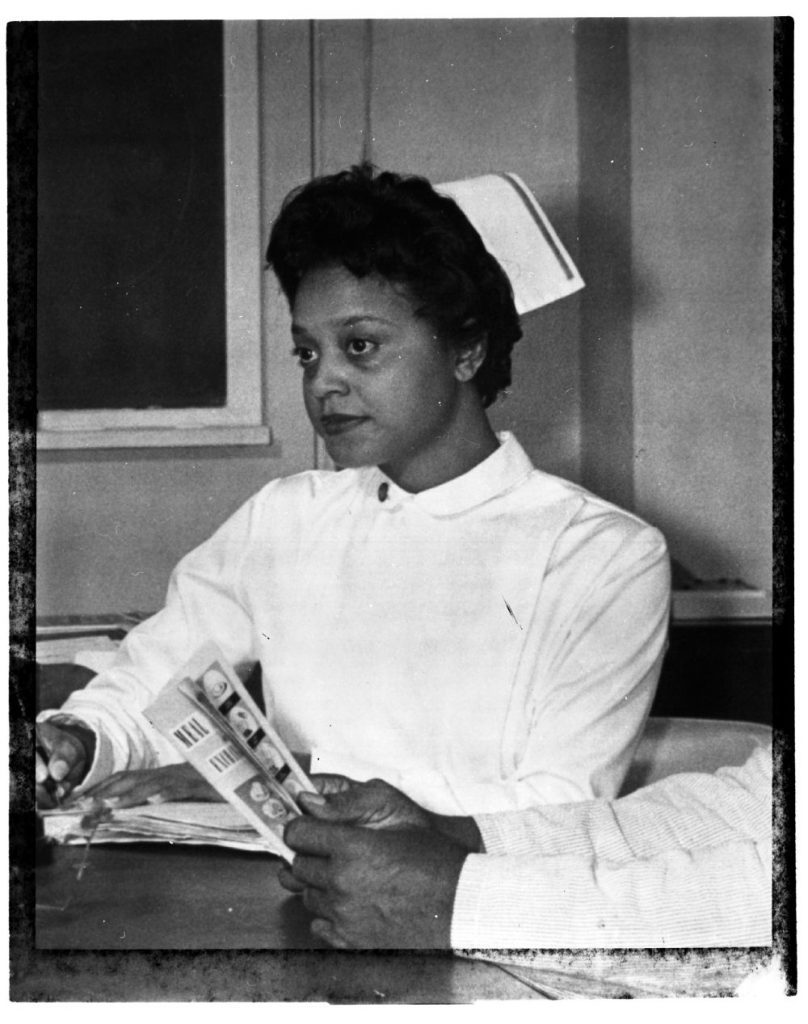

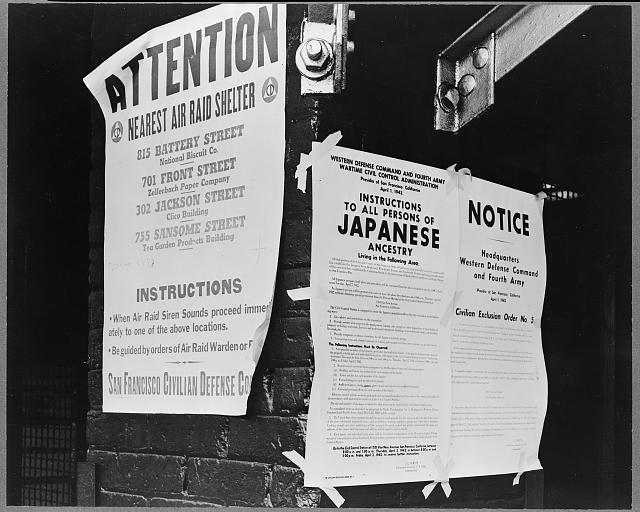

Source: Library of Congress, Reproduction Number: LC-USZ62-34565.

Estrella discusses the mass displacement of Japanese immigrants after WWII, as well as the obscured and unknown history of Japanese Mexicans. In addition to the criminalization of Japanese migrants following the bombing of Pearl Harbor, working-class migrants in Mexican states such as Coahuila encountered discrimination through forced relocation. Similarly, Inouye highlights the misconstrued narrative of the Nikkei community in the U.S., which is made up of Japanese descendants who have permanently settled abroad. These communities were placed in incarceration camps under the War Relocation Authorities on land where native tribes’ reservations were located. Wartime systems of relocation and incarceration draw direct comparisons to the processes of settler colonialism. Due to the consistent reinforcement of white power, the stories of Japanese migrants and the entanglement of injustices are left unheard of in social spheres, education, and sometimes within families. So, how can these narratives be retold and amplified? For many, the answer lies in the ability to convey memory and empathy in a historical context.

Fragments of memory, combined with empathy, can be utilized to translate and preserve the overlooked histories of both immigrant and Indigenous communities. The usage of memory as a historical source allows for these stories to be retold, drawing connections between systems of incarceration, racialization, and dispossession that affected numerous non-white populations in the United States. For example, there are major gaps in the poorly documented history of Japanese Mexican families, and the usage of empathetic agency can bridge connections across the divide. Narrating history through a first-hand perspective also allows for the descendants of those affected to share the intergenerational impacts of settler colonialism and exclusion, demonstrating the long-term impacts. The preservation of these hidden narratives offers new perspectives on the underrepresented history of Japanese migrants while also integrating emotional analogy, remembrance, and personal influence. Incarceration rooted in white dominance continues to be a relevant issue in the United States. Consequently, it is crucial to remember and extend the narratives of Japanese migrants through mechanisms of memory, empathy, and knowledge, to break the cycle of ethnic erasure and carceral systems of injustice.

Lucero Estrella is an Assistant Professor of Ethnic Studies at Lawrence University

[1] Karen Inouye, “No Simple History: Nikkei Incarceration on Indigenous Lands,” Journal of Transnational American Studies, 15(1), 2024.

The views and opinions expressed in this article or video are those of the individual author(s) or presenter(s) and do not necessarily reflect the policy or views of the editors at Not Even Past, the UT Department of History, the University of Texas at Austin, or the UT System Board of Regents. Not Even Past is an online public history magazine rather than a peer-reviewed academic journal. While we make efforts to ensure that factual information in articles was obtained from reliable sources, Not Even Past is not responsible for any errors or omissions.