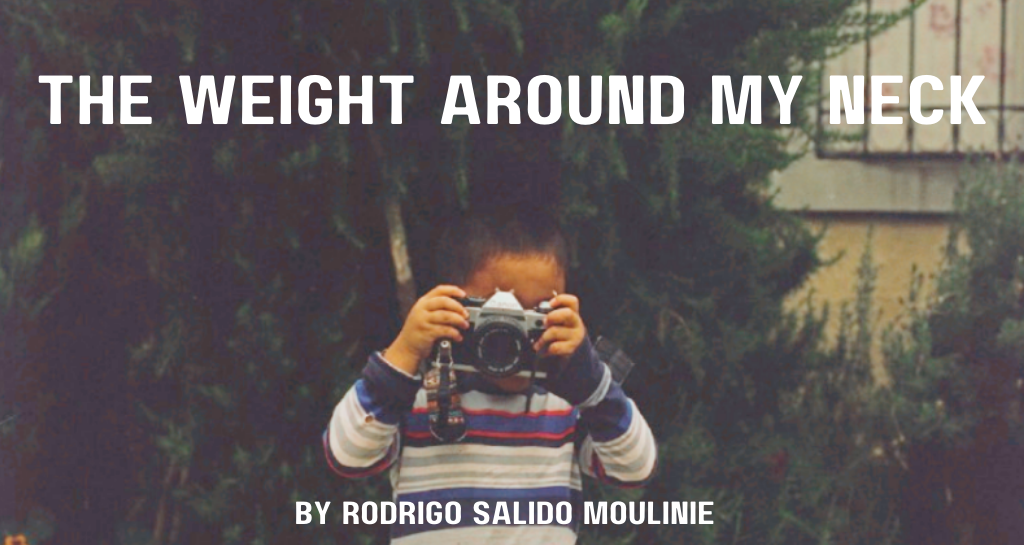

Pick up the camera. Aim, kneel, shoot. He hides behind a pair of rough hands. Inscribed in the knuckles: “Lupita.” Another shot followed by instant regret. Somehow, taking that photograph reminded you of the power dynamics—the violence—immersed in the asymmetrical act of representing others. Let the camera hang around your neck again. It never felt heavier. Engage. You are told only half of the story, maybe because of fear, or maybe you don’t deserve it yet. He walks away just as you take one last picture. The scar on his back might know the other side of the story.

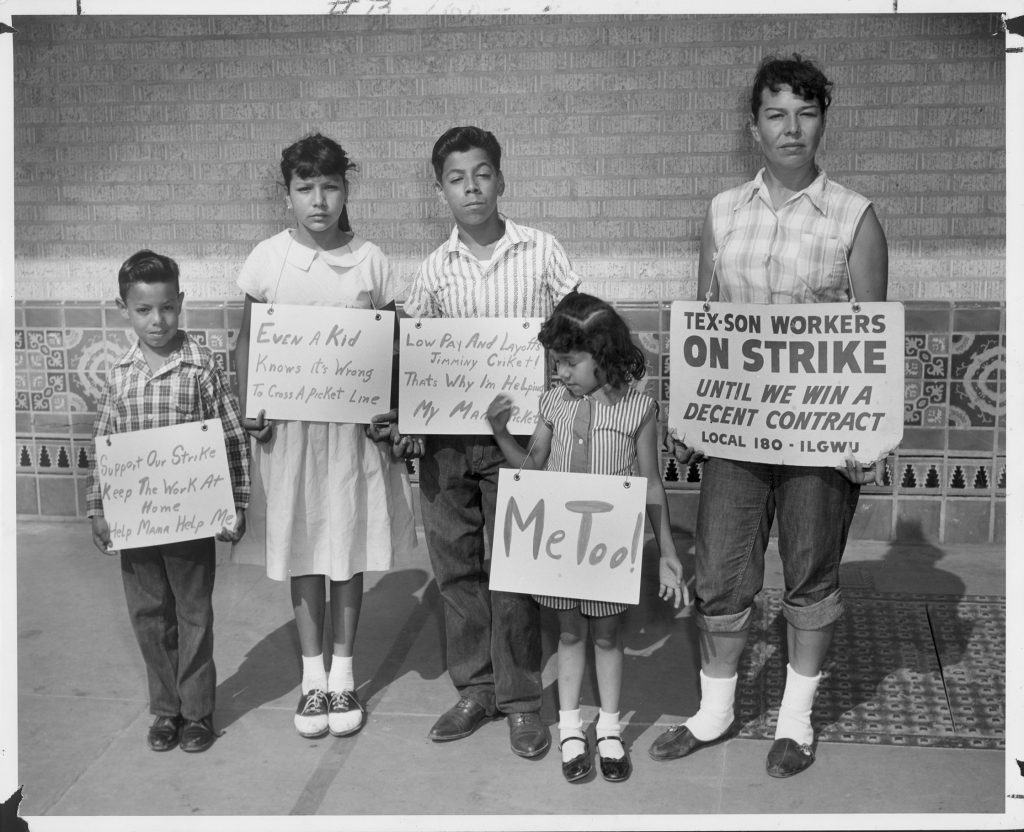

The scar is a large tattoo of Santa Muerte, the Mexican folk saint of death. Canonized by no one yet a saint still, Santa Muerte pulls together a wide range of devotees across Mexico and among Mexican immigrants in Queens, New York. They ask her to help them with legal troubles, protection from the police, health issues, and love affairs. Arely, a transgender woman from Tlapa, Guerrero, is the leader of the movement in New York. She introduced me to many devotees who generously shared their stories with me.

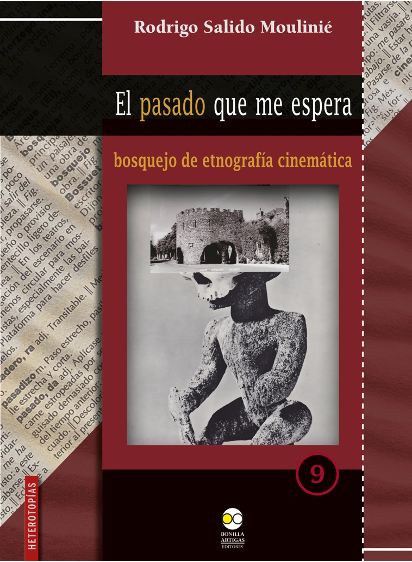

The results of those conversations turned into my first book, El pasado que me espera: bosquejo de etnografía cinemática,[The Past that Awaits Me: A Sketch toward Cinematic Ethnography] where I try to tell these stories without bending them, to avoid privileging the frame over the content. More than showing what I learned, the book reads like a constant struggle about what to do with these stories, who they are serving, and how to write them. Investigating the politics of representing the asymmetry between researcher and researched, between writer and believer, became the book’s core and of all my subsequent work.

The book explores the politics and poetics of ethnographic representation and the troubles of writing about others and picturing them. And it offers a possible escape: to incorporate my photographic practice into the research and bend the writing as much as the ethnographic experience demands it, to use the conventions of cinematic discourse (moving the camera, montage, cuts, close-ups) that diminish the “effect of the real” without discarding its narrative power. Drawing on two years of fieldwork on Santa Muerte—a Mexican folk saint usually described as the patron saint of the Drug Wars in Mexico—I essay across genres to avoid the exoticizing, one-sided descriptions that frame its devotees as criminals, sicarios, or deviants. It exploits the diversity of this devotion and the violence inherent in reducing it to a narco-saint.

El pasado que me espera is divided into three parts. Part I, the book’s core, is an experiment in ethnographic writing that borrows techniques from cinematic discourse, photography, and archives to offer a portrait of the diverse devotion to Santa Muerte: a polyphonic, multi-sited ethnography. Yet, written as a pastiche or collage, it sometimes reads like a novel based on extensive fieldwork, challenging many of the conventions of more traditional ethnographic narratives.

Parts II and III can be considered appendices separated from the empirical text. Part II offers an essay explaining how religious practices and beliefs are represented in Santa Muerte studies and other works on popular religions. It traces how “religion” and its “persistence” came to be conceived as research problems in the social sciences, which makes the appearance of functionalist arguments almost inescapable: devotees believe because they are poor, ignorant, or because they live in violent worlds. Anchoring the text in my fieldwork on Santa Muerte in the context of the rise of the New Atheism movements and social anxieties of modernity, the chapter takes Ludwig Wittgenstein’s method seriously to give agency and meaning back to religious beliefs: to describe, instead of explaining.

Part III delves into the poetics and politics of ethnographic writing and representation. Using the history of photography and its ambiguous connections to cinematography as a parallel, it unveils the violence and mediation inherent to any form of representing otherness. By showing how academic writing borrows conventions of photography—frame, focus, first and second plane, depth, presence—it then proposes to keep borrowing, but from cinematography—montage, lending the camera, “subjective shots,” cutting—to give ethnographic writing the experience of the real while at the same time underscoring its fictitious foundations.

How the text came to be at all warrants an explanation. It all started as a traditional project in ethnography: to embark on a qualitative study to examine and transcribe the life of people who had something in common: believing in Santa Muerte. To understand their beliefs and try to articulate them, I attended baptisms, weddings, Sunday mass, and occasional parties. But this approach soon fell apart and turned into something else: a hybrid, polyphonic text, with the argument lying somewhere between the content and the form. Without a clear path, a pastiche of essays, book reviews, urban reportage, history, auto-ethnography, and loose ends escaped my fingertips. Something got in the way, but what exactly that thing was remained unclear. On the one hand, the text reflects my inability to reduce what I witnessed in the field into a linear ethnographic report, an unwillingness to betray the stories so they could fit a frame. On the other, it reveals the weight I was carrying around my neck. Literally, the weight of the camera.

Fieldworkers generally carry their cameras without giving them too much thought.[1] As an innocuous recording device, the camera serves as a backup memory and to assert presence: an evidence-making machine. Some even echo Margaret Mead, one of the most prominent and controversial anthropologists of the twentieth century, who thought that the perfect ethnographic record would be something close to a film camera standing on a tripod in the corner of a room: infallible, unaltered, scientific.[2] Others follow the methods of Bronislaw Malinowski, another very prominent and complicated anthropologist, who used the camera with foresight and care to build an archive of fieldwork itself to assert his presence in the field. He appears constantly in his clearly posed field photographs to convey the hardships, loneliness, and remoteness that serious anthropological work entails. Ethnographic photography seeks to strike a delicate balance to convince its viewers the anthropologist was there without altering the scene to create ghosts.[3]

Yet photographs usually exceed their maker’s intentions. As James Clifford noted in his essay “On Ethnographic Authority,” one of the subjects in Malinowski’s photograph “A Ceremonial Act of the Kula” is looking back at the camera. At first, the picture works as a metaphor for presence but soon begins to diminish its own authority. The illusion of the photograph’s “subjective view” asserts the presence in the scene and brings the viewer to the field: You are there because I was there.[4] But the illusion is broken by that inconvenient stare. When anthropological subjects look back at the camera, they break the spell. They destabilize the infallibility of the camera, and the illusion fades—which may explain why portraits fit so uncomfortably into the ethnographic look.

Estado de México).

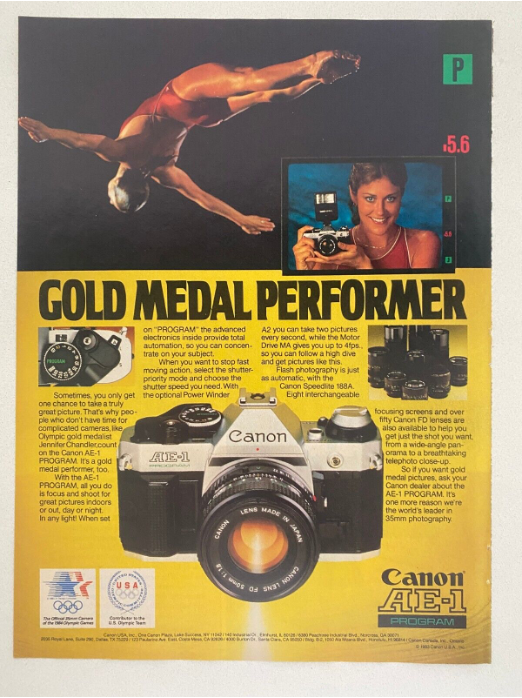

I took the camera everywhere while doing fieldwork between 2015 and 2017 in Mexico City, Boston, and Queens. A 1984 Olympics Edition Canon AE-1 film camera loaded with 100 ISO color 35mm film. Each film had 36 exposures, which makes photographers on a budget think twice before pressing the shutter every time. After 4 or five rolls, my disappointment with the pictures was only matched by my disappointment with the writing. They mirrored each other: impersonal, distant, disengaged. Vague descriptions of religious rituals in my notebooks matched photographs of devotees from behind perfectly. Shy students, it turned out, make bad ethnographers. That became crystal clear. Were bad photographs another sign? Can the camera speak? Overcoming this crisis entailed weaving photographs and words, writing and picturing—a process that became central to my eventual book.

Changing my photographic practice derailed my writing completely. To improve the images, I had to come closer, move differently, make the quotidian strange, and explain the presence of the camera. Photography exacts constant engagement and attention to detail. The images looked different because my body was moving differently. To make a portrait, the operator needs to build a relationship with the subject, articulate the reasons behind the documentary impulse, and accept the trade-off it implies: to reveal their intentions. A portrait is the snapshot of a conversation; it is always the trace of an encounter, a visual dialogue where no side can remain silent. And my first distanced, impersonal photographs of devotees did not lie: I was too afraid to talk.

Conversations triggered by the camera yielded better ethnographic insights. The excuse of a picture gave me an easy entry to casual small talk, tattoo stories, and revealing insecurities. Encounters that would grow into more delicate dialogues. The Canon became my badge and amulet. I wore the strap like a uniform. But it also became a threatening presence. Some people refused to be photographed, and others dismissed camera-bearers as untrustworthy outsiders and remained silent. Portraits rarely come without strings attached: Where will you publish these? Will you send me a copy? How do I look? What do you want it for? It soon became clear: the politics of ethnography and photography overlapped, and that intersection was what the project became about.

poses with her personal statuette.

A Virgen de Guadalupe guards a door that leads to her private Santa Muerte altar.

El pasado que me espera navigates the intersection, embracing complexity and incompleteness. Its fragmented narrative seeks to evoke the tension immersed in visual methods: exposure time, focus, frame, close-ups, composition, and cuts. Moving the camera, lending it, making it stay still, allowing it to think—and letting the portraits speak for themselves. Yet against my best intentions, the writing never relieved the weight of the camera. It feels as heavy and intrusive as the first day, but the neck pain remains instructive. I still carry it as an amulet, a marker of how indebted I am to these stories, and as a reminder that not only does getting closer yield sharper images and more intimate portraits: it is a responsibility.

*All the photos in this piece are by the author.

Rodrigo Salido Moulinié is a writer, photographer, and doctoral student in the Department of History at the University of Texas at Austin, where he is a Fulbright-García Robles Scholar and a Contex Doctoral Fellow. In 2023 he was awarded the Leonard A. Lauder Fellowship in Modern Art at The Metropolitan Museum, where he will be working on his research project: “Covarrubias’ Crossings: Art, Science, and the Global Politics of Ethnographic Image-Making.” Rodrigo’s work explores the interconnections between the histories of photography, science, and anthropology. He traces the tensions between the making of ethnography and the development of new visual methods of representing otherness—photography, painting, sketching, and writing.

[1] I use the term “fieldworkers,” widely used in anthropology, to include ethnographers, artists, photographers, and other disciplines that go “to the field” without being scholars or trained anthropologists.

[2] “For God’s Sake, Margaret, Conversation with Gregory Bateson and Margaret Mead,” The CoEvolution Quarterly 10 (1976).

[3] See Terence Wright, “The Fieldwork Photographs of Jenness and Malinowski and the Beginnings of Modern Anthropology,” JASO 22 (1991), pp. 41-58; Michael W. Young, Malinowski’s Kiriwina: Fieldwork Photography, 1915-1918 Chicago, University of Chicago Press, 1998.

[4] James Clifford, “On Ethnographic Authority,” in The Predicament of Culture, Cambridge, Harvard University Press, 1988. See also Johannes Fabian, Time and the Other: How Anthropology Makes Its Object, New York, Columbia University Press, 1983.

The views and opinions expressed in this article or video are those of the individual author(s) or presenter(s) and do not necessarily reflect the policy or views of the editors at Not Even Past, the UT Department of History, the University of Texas at Austin, or the UT System Board of Regents. Not Even Past is an online public history magazine rather than a peer-reviewed academic journal. While we make efforts to ensure that factual information in articles was obtained from reliable sources, Not Even Past is not responsible for any errors or omissions.