In Surgery and Salvation, O’Brien traces the history of reproductive injustice in Mexico, taking a longue durée approach extending from the late colonial period through post-revolutionary state formation. She focuses on reproductive surgeries and how women’s bodies—particularly those of poor and Indigenous women—became laboratories for medical experimentation, religious morality, and eugenic population control.

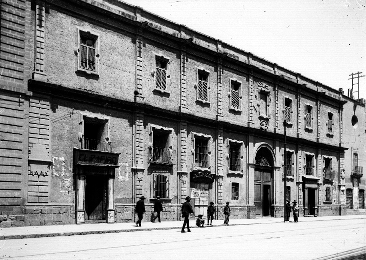

Much historical scholarship on reproductive control focuses on eugenics, a pseudo-scientific movement that flourished in post-revolutionary Mexico in the 1930s. It sought to “improve” the population for nation-building purposes by promoting the reproduction of the “fittest.” During this time, medical authority over the body was already well consolidated. O’Brien broadens the chronological scope and focuses on periods where claims of authority over definitions of citizenship, personhood, life, and death were being contested, such as the process of secularization during the Liberal Reform of the 1850s and state-making post-Revolution (1921-1940).

Structured in five parts, the book argues that surgical technology was seen as a means for salvation in three distinct and chronological ways: saving unborn souls under the Church’s rule during the late 18th and early 19th century; saving the honor of elite unwed women during the reform in the 1850s and the Porfiriato (authoritarian military dictatorship from 1876 to 1911); and saving the nation from the reproduction of “ undesirable” citizens in the aftermath of the revolution, from 1921 to 1940.

O’Brien shows how reproduction was stratified along lines of race and class, resulting in marginalized women disproportionately subjected to coercive reproductive practices. She traces the performance of cesarean operations on dead and dying women to salvage the soul of the fetus, ovariotomy as a medicalized solution for hysteria, and experimental ‘therapeutic’ abortions (those performed for medical reasons). She also examines hysterectomies for unwed elite women, obstetric violence, vaginal bifurcation, tubal ligation, and eugenic sterilization to manage the size and composition of the population. Notably, she challenges the prevailing notion that state-led eugenic forced sterilizations were not widespread in Mexico.

The concept of reproductive governance—the entanglement of social, economic and political structures that produce and regulate reproductive practices— serves as a framework to understand how different powerful actors across centuries tried to control and surveil reproduction. Throughout the book, she traces a throughline that links women’s bodies to modernization, development, and state-building, showing how women were cast as the bearers of the nation, their bodies tasked with producing and embodying national aspirations. Accordingly, the fetus also underwent shifting symbolic meanings, from a religious subject in the hands of the Church in the late colonial period to a biological object as seen from the eyes of secularized technocratic elites to potential citizens that would build postrevolutionary Mexico. At each stage, women’s bodies were the tools, but their needs, desires for autonomy, and sheer personhood were rendered an obstacle—something to be managed, medicalized, and intervened in service of state goals.

Hospital de San Andrés. 1905. Source: Wikimedia Commons

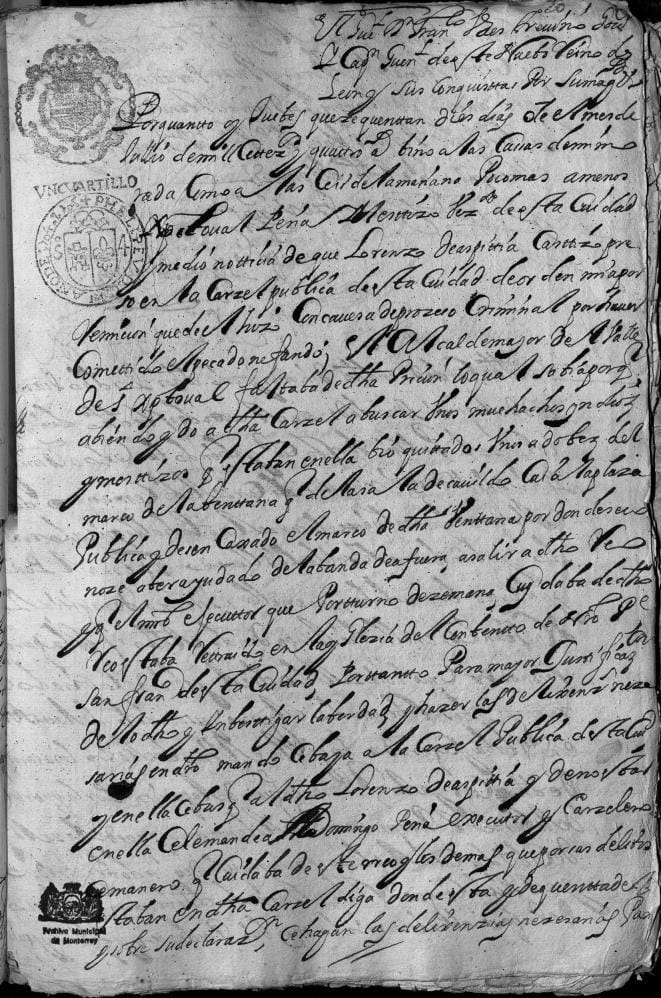

The book draws from an impressive range of sources, from ecclesiastical and mission records to medical students’ theses and hospital records. When describing her sources, she reflects on the voices they contain and the silences they produce, critiquing the fact that most represent the perspectives of elite men. In line with feminist history and methods, she relies on creative pathways to access patients’ voices and the “resistance echoes,” as she calls them, contained in her sources. In this case, resistance materialized in complaints women submitted about medical malpractice. She approaches these stories with care, empathy, and a historical sensibility that reminds us of these people’s lives beyond being reduced to patients of these surgical interventions. Her focus on resistance, pain, grief, and the harms of scientific racism—pseudoscience used to justify racial hierarchies—prevents the reader from becoming desensitized to the injustices she describes.

Challenging the assumption that Mexico was a mere receptacle of European scientific knowledge, practice, and ideologies, the author argues that powerful local actors crafted idiosyncratic yet transnational theories, techniques, and networks, particularly around race. For instance, she traces continuities between American anti-Black medical racism and anti-Indigenous discrimination in Mexican healthcare. This racist logic was not strictly biological. Mexico’s ethnic history and categorization made for medical epistemologies that had a slippery, flexible notion of race. It drew not only on biologized difference but on more diffuse notions of hygiene, class, culture, education, and language. In this context, it was not contradictory to romanticize indigenismo—a political ideology that seeks to celebrate Indigenous legacy while assimilating Indigenous peoples into the nation-state—as a cultural heritage while mistreating Indigenous women.

Class and its entanglements with race emerges as another powerful stratifying line in O’Brien’s narrative. The growth of ‘therapeutic’ abortion, artificial premature birth, and hysterectomies for elite unwed women in the Liberal Reform period illustrates how women’s reproductive lives and medical intervention were enmeshed with gendered notions of middle-class feminine respectability. When these elite women asked for sterilization, they were met with refusal, while poor and Indigenous women were coercively sterilized. Doctors became gatekeepers of gender and agents of the state, using their expert authority to morph the population in line with the racial and class-based desires of the nation.

An Indigenous woman walking in Mexico. Source: Wikimedia Commons

Surgery and Salvation’s focus on technology illuminates how surgical knowledge developed hand in hand with racist, classed, and gendered notions of women’s bodies as sites of intervention. Technology became a means to turn subjective biases into objective, quantifiable “evidence” with the help of techniques such as craniometry or pelvimetry, giving social hierarchies the veneer of science.

O’Brien ends the book by taking us to the present day, where reproductive injustice is still a reality with a history that stretches back well over 200 years. At the same time, she highlights how contemporary feminist advocacy and long-standing activist efforts have contributed to a tremendous wave of abortion legalization throughout Latin America. This transformation is currently afoot and redefining the reproductive justice landscape in the region.

Surgery and Salvation. The Roots of Reproductive Injustice in Mexico 1770-1940 is an outstanding book that reminds us that reproductive injustice is not a thing of the past. It shows the dangers of thinking about women’s bodies as tools for science and state-building in a history that should serve as a cautionary tale for contemporary debates about fertility decline and shifting legal landscapes around reproductive rights in Mexico, the U.S., and around the globe.

Daniela Sánchez is a doctoral student in the Department of Sociology at The University of Texas at Austin. She is a Mellon/ACLS and Fulbright-García Robles fellow. Her research examines reproductive governance around abortion in contemporary Mexico. Before joining the department, Daniela was a consultant for UN Women-Mexico.

The views and opinions expressed in this article or video are those of the individual author(s) or presenter(s) and do not necessarily reflect the policy or views of the editors at Not Even Past, the UT Department of History, the University of Texas at Austin, or the UT System Board of Regents. Not Even Past is an online public history magazine rather than a peer-reviewed academic journal. While we make efforts to ensure that factual information in articles was obtained from reliable sources, Not Even Past is not responsible for any errors or omissions.