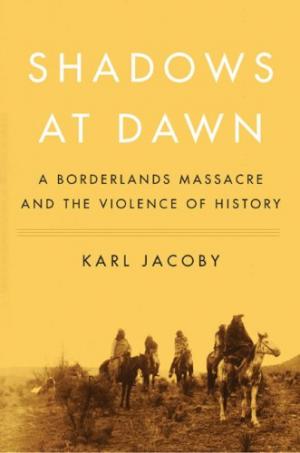

In Shadows at Dawn, Karl Jacoby examines the way that perspective influences historical memory and the role that political power plays in selecting which memories become codified in the historical narrative.  Jacoby does this through a study of the Camp Grant Massacre—the death of approximately 140 Apache at the hands of a group of white and Hispanic settlers and Tohono O’odham natives in April 1871 in the Aravaipa Valley in Arizona.

Jacoby does this through a study of the Camp Grant Massacre—the death of approximately 140 Apache at the hands of a group of white and Hispanic settlers and Tohono O’odham natives in April 1871 in the Aravaipa Valley in Arizona.

Jacoby examines the settlement of the Arizona-Mexico border region from four perspectives, those of the Apache and O’odham natives, the settlers from Mexico, and settlers from the United States. He relates each group’s story individually, highlighting events forgotten, dismissed, or emphasized, and demonstrating the way each group created a unique narrative about a shared event. In doing so, he calls attention to the influence of numerous factors, that influence the creation of history and group memory, including a culture’s worldview and its political position within the larger social context.

Divided into two overall sections—before and after the Aravaipa massacre—Jacoby begins each group’s narrative with its arrival in the area northeast of the Gulf of California, in present-day southern Arizona (in the case of the O’odham, whose arrival in the area is uncertain, a discussion of its lifestyle before the other groups’ arrivals). Jacoby discusses each group’s interaction with the others from its own perspective, which he gleans by studying historical and biographical narratives, or artifacts with analogous function among the indigenous groups. By addressing the way each group interpreted common events common, for example the cause each group attributed to the Aravaipa attack, Jacoby theorizes about the way that each group envisioned its role in the conflict, and more broadly, the way that it interpreted life in the rugged Arizona territory.

Jacoby’s study presents a fairly straightforward analysis of the events leading up to the Araviapa Canyon attack and does not attempt to present a theoretical explanation for the violence of the frontier or colonialism. The major contribution of Shadows at Dawn, however, is Jacoby’s portrait of each group’s distinctive perspective on the same time period—and, in some cases, the same events. This is particularly useful in postcolonial or subaltern studies, for recovering the voices that are lost when, as is frequently the case, only the history of the dominant or victorious community has been preserved. Jacoby’s approach, however, also highlights the difficulty of subaltern histories—preserving the perspective of conquered peoples, which tends to be lost or destroyed. What fragments remain—in his account the calendar sticks of the Apache serve as an example of these historical remnants—generally paint an unclear or incomplete picture, at best, and the historian must engage in some degree of speculation to construct a narrative based upon them. This is particularly true when dealing with semi-literate groups like indigenous North Americans.

Despite this difficulty, Jacoby utilizes the extant material effectively and acknowledges the challenges that it presents. The result is unique both in its approach and analysis and makes for a readable and accessible study, which avoids the all-too-common trap of theoretical overreaching.

Further reading:

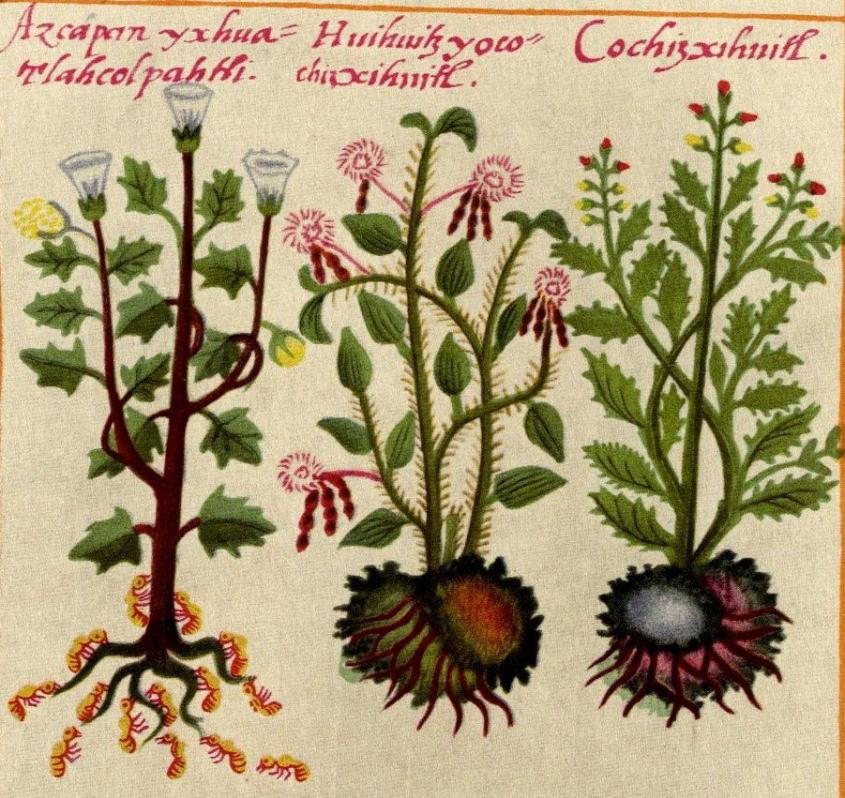

The Codice de la Cruz-Badiano is an example of the encounter of between writing systems, and thus of systems of knowledge, with multiple swings from the pictographic-glyphic tradition to the alphabetical. The illustrations are by no means subordinated to the writing. Visual evidence and linguistic analysis of Náhuatl offer ways of approaching the complexities of cultural forms and to provide information about natural history that was not present in the Latin texts.

The Codice de la Cruz-Badiano is an example of the encounter of between writing systems, and thus of systems of knowledge, with multiple swings from the pictographic-glyphic tradition to the alphabetical. The illustrations are by no means subordinated to the writing. Visual evidence and linguistic analysis of Náhuatl offer ways of approaching the complexities of cultural forms and to provide information about natural history that was not present in the Latin texts.