By Charley S. Binkow

Perhaps no figure in American history has been studied more than Abraham Lincoln. A man of profound importance, intellect, and ambiguity, Lincoln has been a source of fascination for scholars, students, and Americans for generations. There are innumerable documents centered on Lincoln and his legacy, which are now accessible to everyone via The Lincoln Archives Digital Project.

According to their website, the digitalization project, which started in 2002, is the first project to scan “the entire contents of a president’s administration.” That’s a lot of stuff—by project’s end, they will have approximately fourteen million images. But they do a wonderful job of organizing their growing collection. There is a search option to the archive for those who know what they’re looking for. For those who just want to browse, I would recommend starting with the website’s interactive timeline. This screen not only gives one a comprehensive history of Lincoln’s life, but it also supplements dates with a ticker-tape news display of global history. For example, you can learn that in 1811, two years after Lincoln’s birth, the Grimm brothers published their famous fairy tale collection.

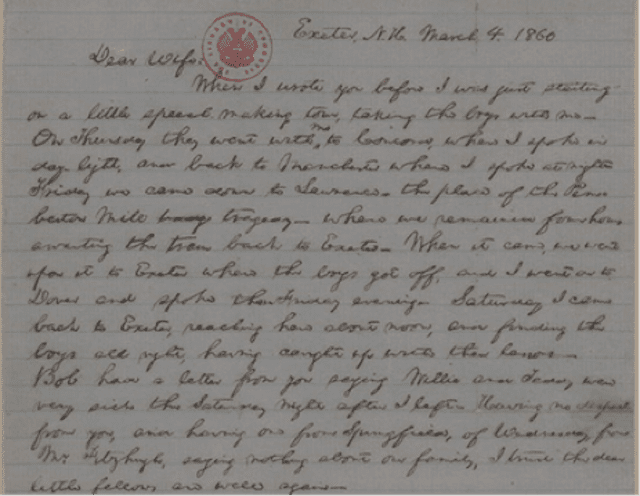

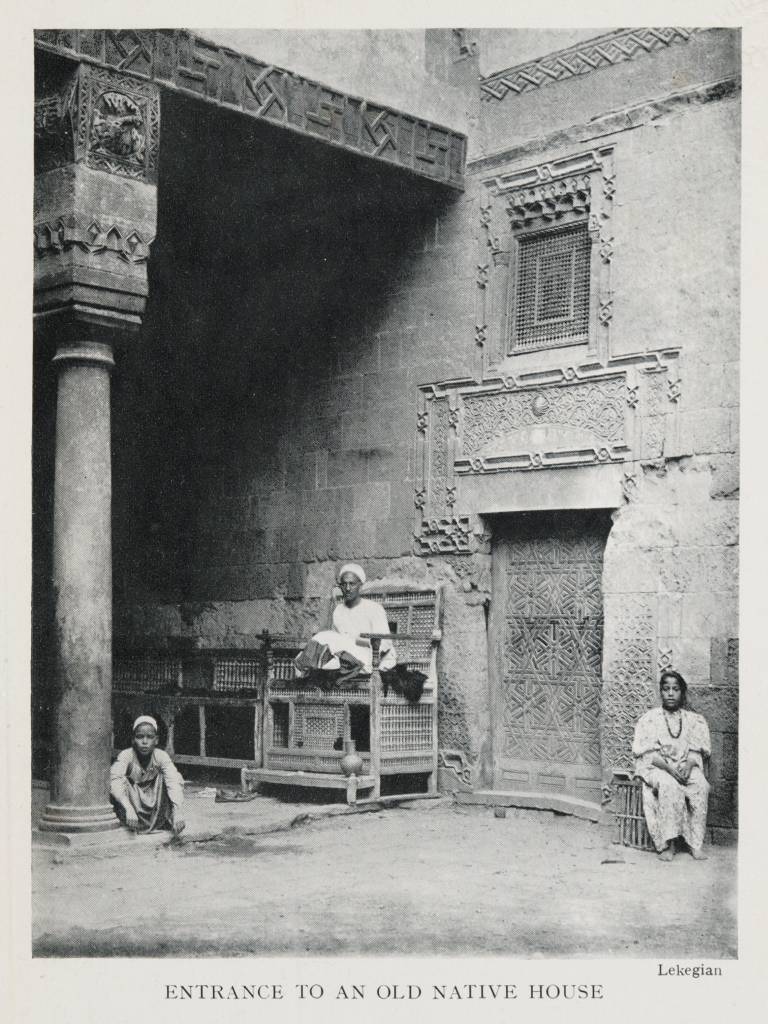

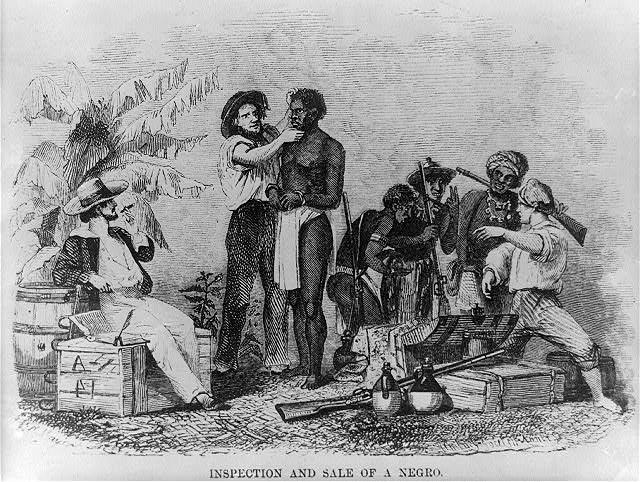

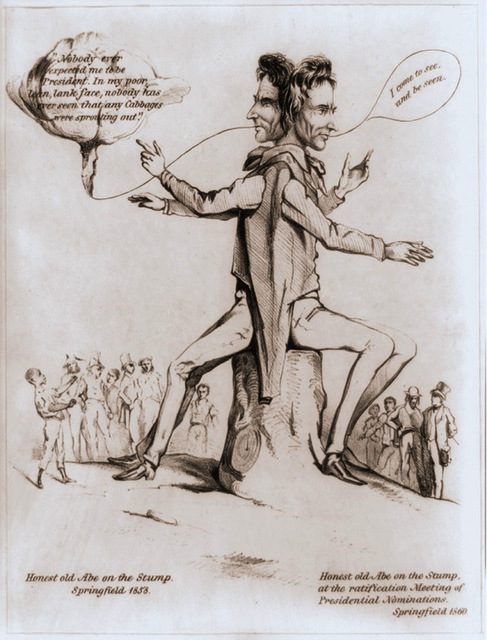

Honest old Abe on the Stump, at the ratification Meeting of Presidential Nominations. Springfield 1860. Courtesy of the Library of Congress

From that page, one can head to the documents section to read Lincoln’s personal writings. I recommend reading the letters he sent to Mary Todd—one can really feel how much he misses her while he’s traveling.

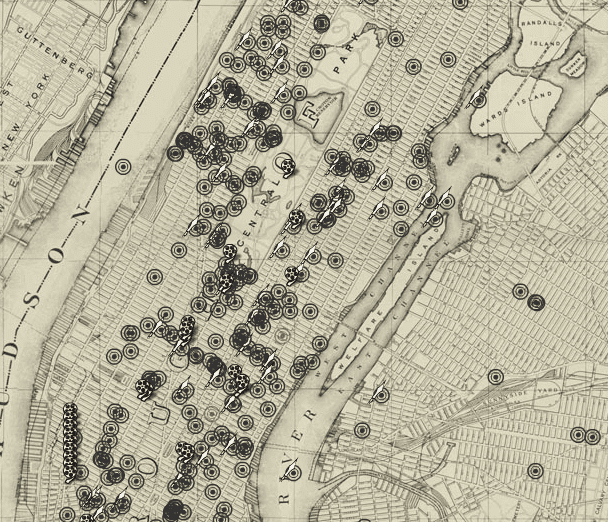

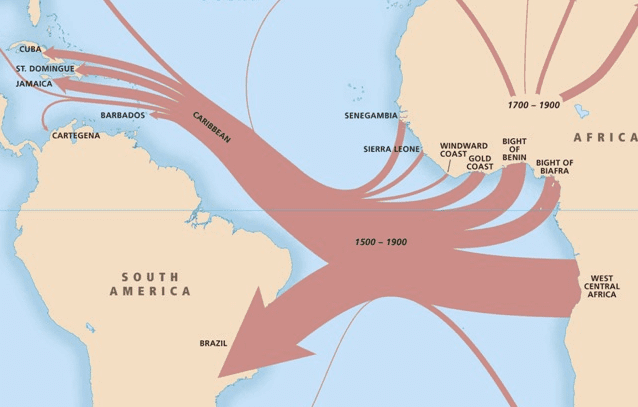

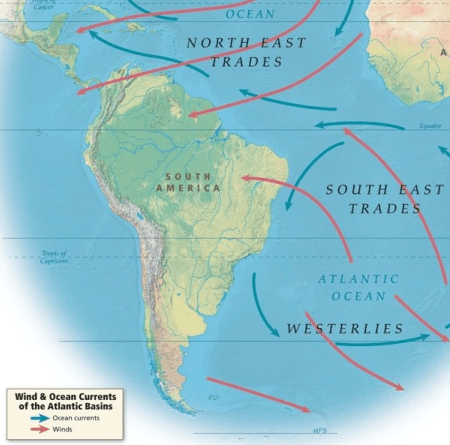

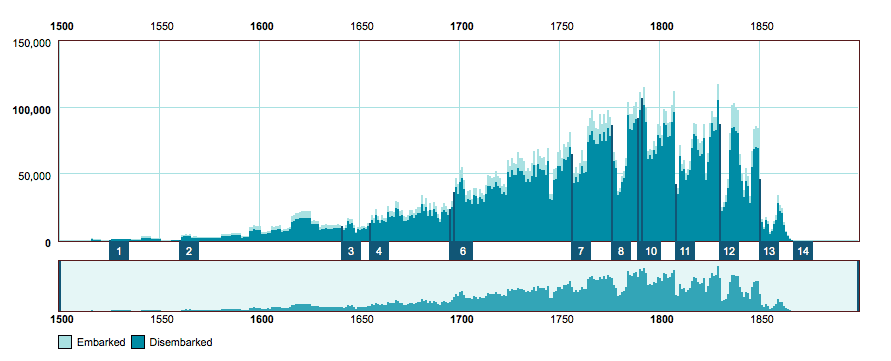

The website also gives researchers the chance to explore Lincoln’s world. I would suggest looking at the maps section located on the left. One can explore city maps, battle maps, maps of foreign countries, and maps of territories.

The newspaper section is a must. The website breaks the papers up by north and south and lets you peruse to one’s heart’s content. The editors of the site also give the reader a chance to explore the history of the newspapers/magazines and suggested future readings.

This is a fruitful and expansive archive. And it’s only getting bigger. I have already found useful information for my own research, and I’m sure any scholar can find something of use here for theirs. But to any American history enthusiast, this is a playground of documents, pictures, and downright interesting stuff.

Catch up on the latest from the New Archive series:

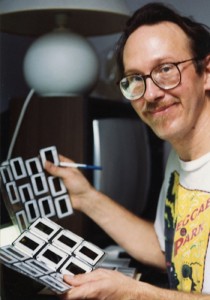

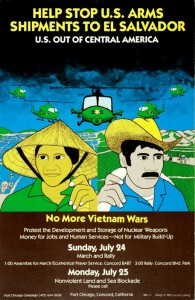

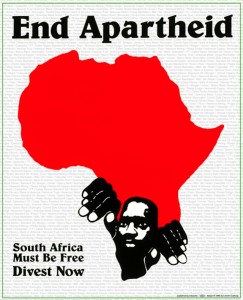

Joseph Parrott highlighted the digitalized political posters collected by archivist and artist Lincoln Cushing

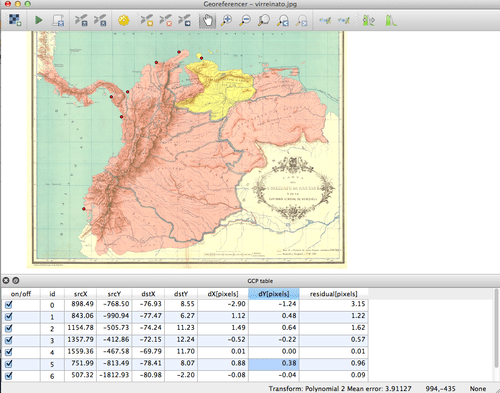

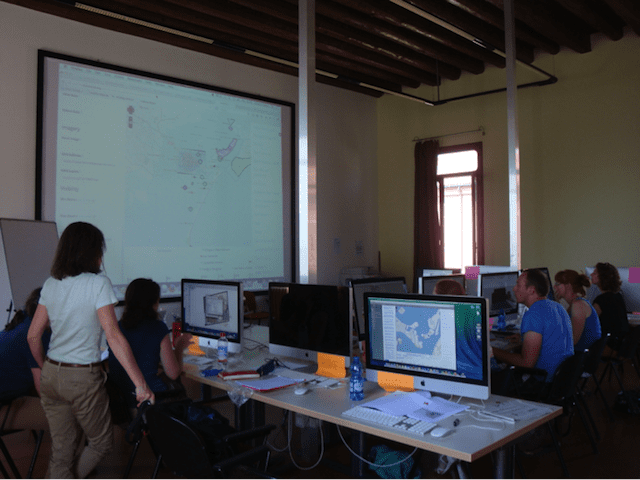

Maria José Afanador-Llach discussed her experience at a Digitilization Workshop in Venice and Daniel J. Cohen and Roy Rosenzweig, Digital History: A Guide to Gathering, Preserving, and Presenting the Past on the Web

Charley Binkow discussed digitalized images from the Folger Shakespeare Library

Charley Binkow explored photographs of California’s Gold Rush

Henry Wiencek found a digital history project that not only preserves the past, but recreates it