The historiography of the Black Death has tended to cast the Ottoman Empire as the “sick man of Europe.” Nükhet Varlık does admirable work in breaking down this Eurocentric view by tracing the Black Death’s history during the rise of the Ottoman Empire, a history she considers as a long process of recurrent outbreaks rather than an isolated event. Varlık frames her work within the historiography of diseases, creatively intertwining environmental history, the history of science, and imperial political history. Moreover, she models how historians can work with up-to-date scientific research, including recent studies in epidemiology, genomics, ecology, and bioarchaeology.

Varlık argues for a correlation between the plague’s epidemiological patterns and the empire’s consolidation, which is visible through the interaction among ecological zones as human and nonhuman mobility increased. These mobile nonhuman agents included fleas, lice, rodents, and the pathogenic bacteria Yersinia pestis, and they determined the plague’s expansion and waves of recurrence. While ‘global’ histories of disease tend to flatten social differences and take connections for granted, Varlık builds upon the idea of a ‘network’—a dynamic set of relationships that assemble the asymmetrical flow of ideas, humans, goods, animals, as well as pathogens.

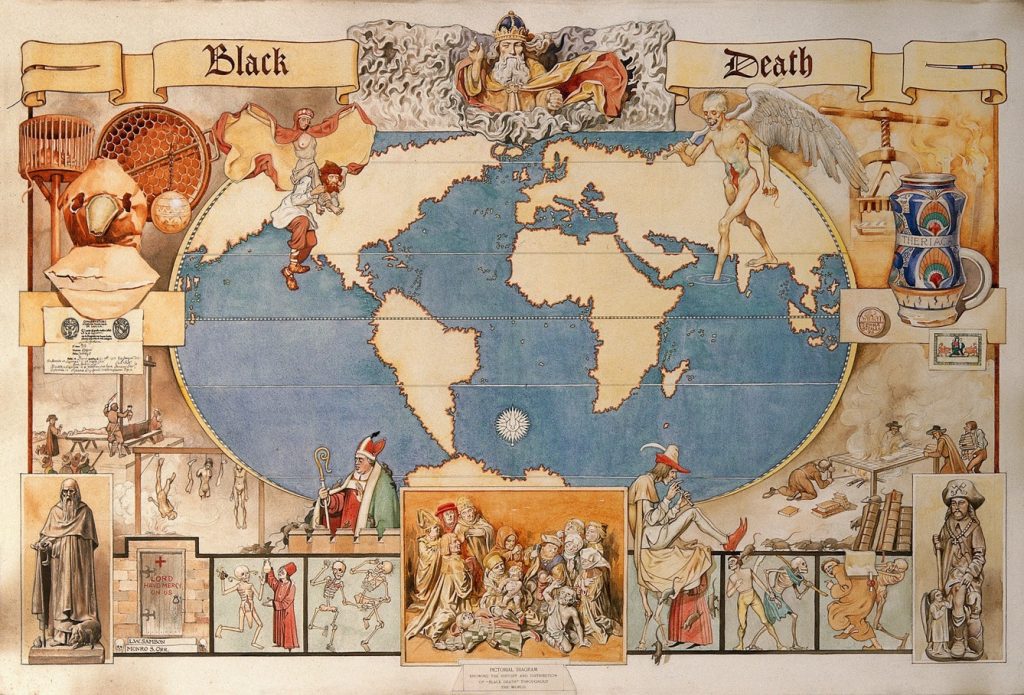

Plague and empire focuses on what conventionally has been called the “second plague pandemic” (the Black Death) —the first being the Justinian plague and the third the East Asian plague. Nevertheless, the second pandemic was not a single discreet event that took place in 1348. It consisted of several waves of epidemics over 250 years. It is no coincidence, Varlık argues, that this period coincided with the transformation of the Ottoman semi-nomadic regime into an extensive empire in the eastern Mediterranean. Therefore, she situates the Ottoman epidemic cycles within the context of imperial expansion and the conquest of cities like Edirne and Istanbul as trade connections with Europe and Asia increased. Thus, she overcomes a variety of historiographic fallacies, including the “westward diffusion of the plague,” Turkish indifference to the Black Death (fatalism), and “epidemic boundaries” between the Christian and Muslim Mediterranean worlds.

Varlık synthesizes historical primary sources with current scientific research on the etiology of the plague, including new understandings about the interaction among hosts (such as rodents, humans, and other mammals), vectors (fleas and lice), and the pathogen (Yersinia Pestis). She also explains how the disease remained “inactive” in wild foci of animals––that is, groups of infected animals that became plague reservoirs. Moreover, she suggests that climate played a role in the migration of some of these hosting species.

The book employs a wide range of documents such as medical treatises, travel accounts, and official reports, not only from Turkish sources but also from Arabic, Byzantine, Italian, and Iberian sources. Although there is an apparent absence of the plague in early Ottoman sources, she explains that it does not mean a real absence of the disease. Instead, she argues that the plague gradually became significant enough to register in Ottoman culture as the empire urbanized and its officials moved between territories. Thus, environmental factors became entangled with perceptions and knowledge about the plague and governmental measures for controlling outbreaks.

Despite its broad regional scope, Plague and Empire centers on Istanbul. Methodologically, this choice makes sense, particularly after its conquest by the Ottomans in 1453, because this new capital became the primary node where imperial and epidemic networks converged. Varlık’s focus on connections helps us understand how Istanbul was not isolated, but the core of governmental processes and the catalyst of epidemic waves in the Western Mediterranean.

Varlık’s model of intertwining imperial history and the flow of disease could productively be applied and tested in other contexts, including different epidemics. For instance, thinking about smallpox epidemics in the Conquest of America––simultaneous in time with this long Black Death––could be a fruitful comparison. Another case to think about is our current context of dealing with COVID-19. Considering its zoonotic origins, environmental drivers, post-modern circulation networks, and the state’s crucial role and supranational institutions to control its spread, we have much to learn from Varlık’s approach.

Plague and Empire in the Early Modern Mediterranean World constitutes a bold and reliable approach to the history of diseases in imperial and globally-connected perspectives. It incorporates current scientific research in ways that make it relevant across disciplines. Varlık carefully links social, political, and environmental analysis. As a result, the book offers not only a crucial addition to the new historiography of diseases but also makes a contribution that is relevant to our present pandemic experience.

Check out Dr. Varlik’s talk at the IHS Climate in Context conference.

The views and opinions expressed in this article or video are those of the individual author(s) or presenter(s) and do not necessarily reflect the policy or views of the editors at Not Even Past, the UT Department of History, the University of Texas at Austin, or the UT System Board of Regents. Not Even Past is an online public history magazine rather than a peer-reviewed academic journal. While we make efforts to ensure that factual information in articles was obtained from reliable sources, Not Even Past is not responsible for any errors or omissions.

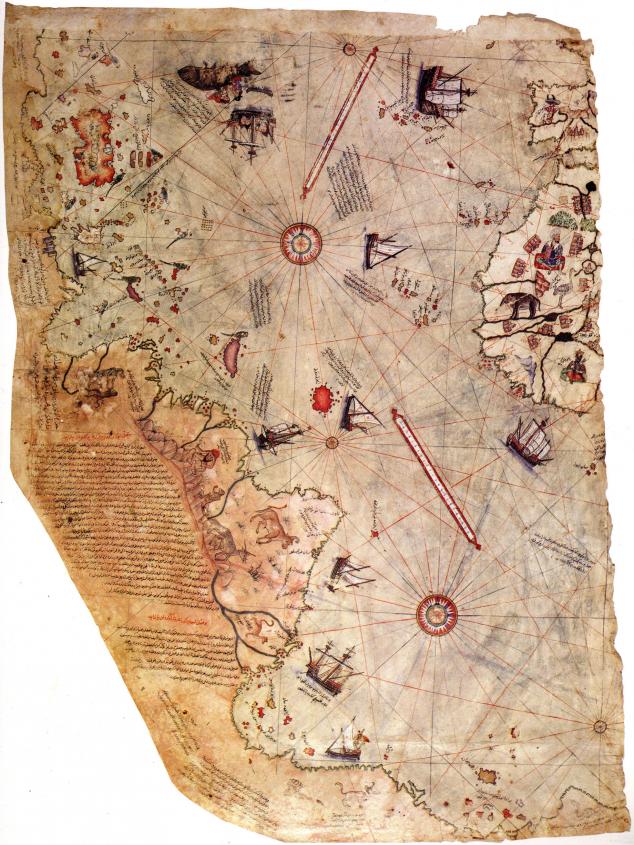

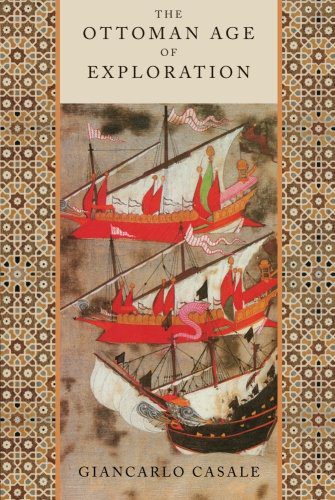

In The Ottoman Age of Exploration, Giancarlo Casale contests the prevailing narrative that characterizes the Ottoman Empire as a passive bystander in the sixteenth-century struggle for dominance of global trade. Using documents from archives in Istanbul and Portugal, Casale shifts our attention east and demonstrates that the Ottomans were actively engaged as rivals to the Portuguese for control of the lucrative spice trade and sea lanes of the Indian Ocean.

In The Ottoman Age of Exploration, Giancarlo Casale contests the prevailing narrative that characterizes the Ottoman Empire as a passive bystander in the sixteenth-century struggle for dominance of global trade. Using documents from archives in Istanbul and Portugal, Casale shifts our attention east and demonstrates that the Ottomans were actively engaged as rivals to the Portuguese for control of the lucrative spice trade and sea lanes of the Indian Ocean.