By Guy Raffa

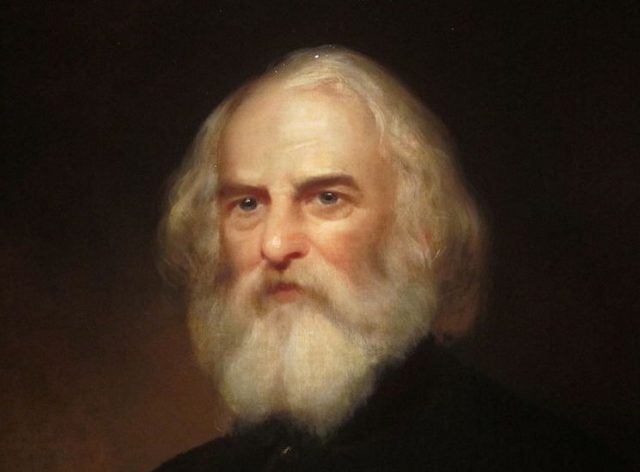

“We breathe freer. The country will be saved.” Henry Wadsworth Longfellow’s response to the reelection of Abraham Lincoln in 1864 is a timely reminder of how, while they all matter, some presidential elections matter much more than others.

Five years earlier Longfellow was one of many who believed the time for peace had passed with John Brown’s execution for attempting to arm slaves with weapons from the federal arsenal at Harpers Ferry. “This will be a great day in our history,” he wrote on Dec. 2, 1859, the day of the hanging, “the date of a new Revolution” needed to move the nation farther toward the Constitution’s goal of “a more perfect Union.” Even “Paul Revere’s Ride,” his famous poem on the Revolutionary War, was “less about liberty and Paul Revere, and more about slavery and John Brown,” writes historian Jill Lepore, “a calls to arms, rousing northerners to action.” This rallying cry serendipitously appeared on newsstands on Dec. 20, 1860, the day South Carolina seceded from the Union.

Longfellow had voted early on Nov. 6, 1860 and was overjoyed by the news of Lincoln’s “great victory,” calling it “the redemption of the country.” His diary marks steps toward fulfilling the promise of this victory, from enactment of the Emancipation Proclamation on Jan. 1, 1863 (“A great day”) and passage of the Thirteenth Amendment, formally abolishing slavery, on January 31, 1865 (“the grand event of the century”) to General Lee’s surrender at Appomattox on April 9, 1865: “So ends the Rebellion of the slave-owners!”

Longfellow had gained notice in abolitionist circles two decades earlier with publication of his Poems on Slavery. He judged his verses “so mild that even a Slaveholder might read them without losing his appetite for breakfast,” but still they triggered a “long and violent tirade” in a South Carolina newspaper and were left out of an 1845 edition of the author’s collected works to avoid offending readers in the south and west.

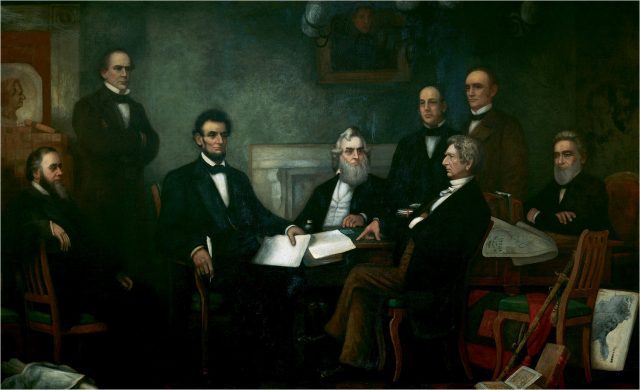

First Reading of the Emancipation Proclamation of President Lincoln, by Francis Bicknell Carpenter, 1864 (via Wikimedia Commons).

In 1863, New York’s Evening Post cast Longfellow as the nation’s prophet. Crediting the poet’s “discerning eye” for foreseeing “the inevitable result of that institution of American slavery which was the black spot on the escutcheon of our republican government,” the paper lamented that his words had gone “unheeded, until the black spot spread into a cloud of portentous dimensions, and broke over the land in a storm of blood and desolation.”

1863 also saw Longfellow complete a draft of his translation of Dante’s Divine Comedy. Working closely with Dante’s poem helped him cope with the traumatic loss of his beloved wife. On July 9, 1861, Fanny had suffered fatal injuries when her dress caught fire as she melted wax to seal a lock of her daughter’s hair. The translation provided “refuge” from an ordeal “almost too much for any man to bear,” he wrote to a friend.

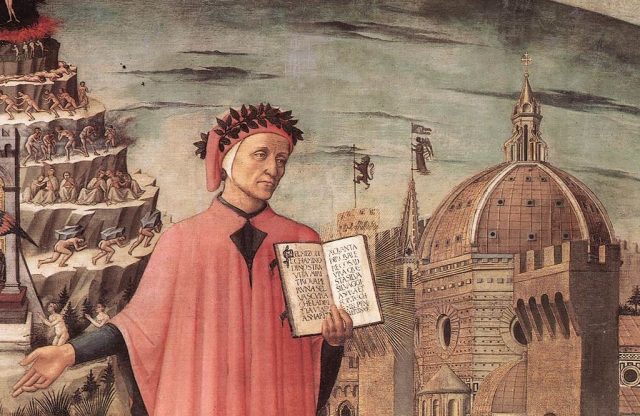

Dante, poised between the mountain of purgatory and the city of Florence, a detail of a painting by Domenico di Michelino, Florence 1465 (via Wikimedia Commons).

Living with Dante’s vision of the afterlife also gave Longfellow some perspective on the war. On May 8, 1862, soon after translating Paradiso, he reflected, “Of the civil war I say only this. It is not a revolution, but a Catalinian conspiracy. It is Slavery against Freedom; the north against the southern pestilence.” The reality of this moral disease hit home when he visited a local jeweler’s shop. There he saw “a slave’s collar of iron, with an iron tongue as large as a spoon, to go into the mouth.” “Every drop of blood in me quivered,” he wrote, “the world forgets what Slavery really is!”

The war to eradicate slavery by suppressing this “conspiracy” brought its own set of horrors. Longfellow was acutely aware of the high toll of death and mutilation on both sides, the destruction extending far beyond the war zone. “Every shell from the cannon’s mouth bursts not only on the battle-field,” he lamented, “but in faraway homes, North or South, carrying dismay and death. What an infernal thing war is!”

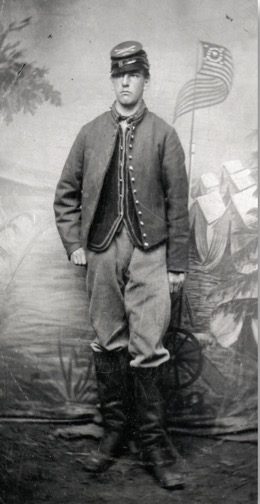

Charles Longfellow in Uniform (1st Massachusetts Artillery), March 1863. Courtesy National Park Service, Longfellow House-Washington’s Headquarters National Historic Site.

The hell of war weighed heavily on Longfellow’s mind when he finally turned to translating Dante’s Inferno—he saved this first part of the Divine Comedy for last—on March 14, 1863. He began during an especially “sad week”: Charles, his eighteen-year-old son, had left home, unannounced, to join the Army of the Potomac in Washington. Initially attaching himself to an artillery regiment, “Charley” benefited from family connections to receive a commission as second lieutenant in the cavalry. “He is where he wants to be, in the midst of it all,” wrote the worried father. During this first month of Charley’s military service, Longfellow translated a canto of Inferno each day. Amid “many interruptions and anxieties,” he completed all thirty-four cantos by April 16, 1863. Two weeks later Charles Norton, Longfellow’s friend and fellow Dante expert, urged him to hold back publication of the translation until 1865 so it could be presented during Italy’s celebration of the poet’s six-hundredth birthday in Florence.

On December 1, 1863, Longfellow received a telegram from Washington saying his son had been “severely wounded.” He immediately left Cambridge with his younger son Ernest and headed south to find Charley and learn the extent of his injuries. The soldier, who had already survived a bout of the ever-dangerous “camp fever” the previous summer, made another “wonderful escape,” as his relieved father put it. Fighting near the front lines in the Mine Run Campaign, Charley took a Confederate soldier’s bullet in the shoulder. He returned home in one piece and slowly recovered from his wounds, but his fighting days were over.

As the war continued and congress worked to repeal the fugitive slave acts of 1793 and 1850, Longfellow resumed editing his translation in preparation for the Dante anniversary. He admired Charles Sumner’s speech on the proposed amendment to abolish slavery: “So long as a single slave continues anywhere under the flag of the Republic I am unwilling to rest.” Longfellow shared his friend’s relatively expansive view of liberty, observing on April 20, 1864: “Until the black man is put upon the same footing as the white, in the recognition of his rights, we shall not succeed, and what is worse, we shall not deserve success.” The following year Longfellow asked Sumner for assistance in having a privately printed edition of the first volume of his translation delivered to Italy in time for the Dante festivities. In the same letter of February 10, 1865, he thanked the senator for his role in abolishing slavery, proclaiming that “this year will always be the Year of Jubilee in our history.”

Longfellow’s translation of Dante’s Inferno took its place among the works by eminent foreigners on display in Florence to honor the poet’s birth. Three days of festivities in 1865 doubled as a celebration of Italy’s independence while the nation awaited the additions of Venice (1866) and Rome (1870) to complete the unification begun in 1859-61. At a banquet for foreign dignitaries, an American speaker drew rousing applause from his Italian hosts and their guests when he toasted the “Re-United States”—a poignant reminder that Italy was taking its first steps as an independent and (mostly) unified nation just as America emerged from the greatest test of its own unity and promise of freedom.

The statue of Dante Alighieri that today stands in the Piazza Santa Croce in Florence was unveiled in 1865 during the festival (via Wikimedia Commons).

Dante’s prominence in these parallel national struggles was clear to Longfellow, as it was to the abolitionist leader Frederick Douglass, the poet H. Cordelia Ray, and other black “freedom readers,” the title of Dennis Looney’s book on the African American reception of Dante and his poem. Longfellow wrote six sonnets on Dante to accompany the commercial publication of his translation of the Divine Comedy in 1867. The final sonnet, composed on March 7, 1866, glorifies Dante as the “star of morning and of liberty,” his message of freedom reaching “all the nations” as his “fame is blown abroad from all the heights.”

“Hideous news.” This was Longfellow’s reaction to Abraham Lincoln’s death on the morning of April 15, 1865, from the bullet fired by John Wilkes Booth the night before at Ford’s Theatre. Star of morning and of liberty: Longfellow’s epithet for Dante would have sounded like a fine description of Abraham Lincoln to millions of Americans who mourned the slain president.

![]()

Jacqueline Jones discusses Civil War Savannah.

Marc Palen debates the causes of the Civil War.

Alison Frazier suggests some “lightly fictionalized” books about the Italian Renaissance.

Check out Guy Raffa’s multi-media journey through the three realms of Dante’s afterlife, via Thinking in Public.

![]()