On June 1982, two pages of official letter sized paper marked by the symbol of the Ministry of Finance made their way across a network of various bureaucratic desks of the National Police of Guatemala. A rural farmer and grandfather from Uspantán in El Quiché, Julio Ortiz (this is a pseudonym for reasons of privacy and safety) was addressing a top-level Police Chief in the capital city about his deep concern for a missing grandson. Kidnapped by a certain state authority figure under the false accusation of subversive activity, Julio’s grandson was missing and Julio had no information as to his whereabouts. The letter was Julio’s plea to the Chief to find out what happened to his grandson, pointing out that such a disappearance was “unjust.”

This and many other similar complaints to authorities, called denuncias, or complaint reports, flowed into the offices of police officials and clerks at an alarming rate during the 36 years of civil war in Guatemala. They represented the responses of people in Guatemala to the widespread political agitation and repression that in some way or another affected their loved ones and friends, a pattern of repression that was the staple of successive governmental regimes with heavy anti-communist agendas since 1954. Julio’s 1982 denuncia belonged to a period in Guatemala’s history when state authorities ignored legal due process, violated civil rights and constitutional guarantees, and maintained widespread impunity for Police and Military actors.

For historians of Guatemala, a document such as this may be only one of a large number of such denuncias, yet Julio’s letter nevertheless serves to help us make educated guesses about the nature of the State Police in Guatemala, about secrecy in the structure of institutionalized violence, and about the relationship between Guatemalan society and its authoritarian figures. What stands out about this document in particular is the number of possible intermediaries involved in producing it and passing it along. To better understand such a document, we can try to recreate the course it ran, before reaching a final audience and a final verdict.

The National Palace in Guatemala City was the seat of the Guatemalan government during the civil war and the target of several attacks (via Wikimedia Commons).

As we zero in on the finer details of Julio’s denuncia, three important trends reveal themselves. First, it is likely that a lawyer or clerk, rather than Julio himself, who was a farmer in a rural town, produced this complaint. The denuncia was typed on formal letter sized paper that had to be bought from the Ministry of Finance. It uses formal language that had to be typed by someone with the resources to do so. The guidelines for what was considered a proper complaint were strict; anything that violated the guidelines would be thrown out.

A formalized complaint-making process was not the only clue that sheds light on the complaint making process. Other traces point to the intervention of a host of different offices, officers, and clerks before the letter reached its final destination. For example, certain stamps and signatures suggest its passing from a local police station or lawyer in El Quiché to the Department of Technical Investigations in the capital, Guatemala City, and then back to the Chief of Police in El Quiché. The back and forth journey of Julio’s letter from the local town to the capital and back was a reflection of the centralized but also dispersed nature of the Police bureaucracy.

Indigenous Ixil people exhume the remains of their disappeared loved ones from a killing field in Guatemala (via Wikimedia Commons).

If Julio had known about the back and forth movement of his denuncia, he still might have hoped his complaint would remain intact. What he had no control over, however, was the fact that the content of his denuncia had to be diluted as it passed through Police offices. A separate cover letter attached to the complaint appeared in front of it. The Inspector General had stamped it, and it also included many clues to suggest that it passed through the hands of one or more clerks in the Inspector General’s office. For example, a one-sentence summary of the contents of the letter appears conspicuously scribbled sideways on the margins, indicating that some clerk in the Inspector General’s office or in the Chief of Police of Quiche’s office wanted to make approaching the document more efficient for the next person who was to read it.

What do these tentative conclusions say about the ability of Julio to make his complaint heard? Efficiency and conciseness were important priorities for police clerks. The diluting of his denuncia and its passing through dispersed offices created distance between the person making the complaint and the highest office where the record ended up. This gap then, contributed to the difficulty for people like Julio to reach authorities and be heard in a more authentic way.

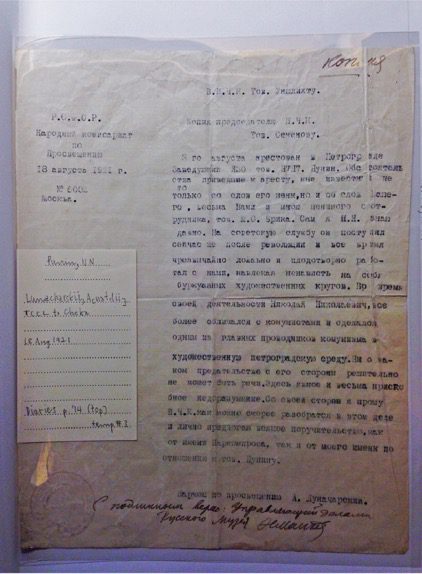

The Guatemalan National Police Historical Archive was discovered in 2005 (via AHPN).

Julio was not likely to receive an answer to his complaint. Like many others, it passed through a complex process of formalizing and diluting while physically moving through a network of intermediaries that was hierarchical and centralized yet dispersed and secretive. Guatemalan authorities rarely responded to inquiries about disappeared or illegally detained family members or friends. This official silence by the police was not simply the product of inaction and indifference. It depended on a concerted effort by various bureaucratic actors to process information and, in so doing, alter its meaning and significance. Over the course of the civil war, thousands of heartfelt denuncias fed an enormous police archive that represented police repression and secrecy.

In a country such as Guatemala with a legacy of state institutionalized violence and impunity, the millions of denuncias such as Julio’s letter, uncovered in the National Police archive, are important tools for seeking justice. Sometimes, they can help uncover links to other documents that serve as further evidence. Thinking about how intermediaries are an integral part of institutional secrecy, we can deconstruct the image of the police state as a homogenous entity. We can locate the responsibilities that rested on the shoulders of important actors at different levels of the authoritarian infrastructure.

![]()

Sources:

Digital Archive of the Guatemalan National Police Historical Archive. For reasons of privacy and safety, I have chosen not to cite the specific location of this document.

Archivo Histórico de la Policía Nacional, From Silence to Memory: Revelations of the Archivo Histórico de la Policía Nacional (Eugene, OR: University of Oregon, 2013).

![]()

You may also like:

Two documentaries on Guatemala’s violent civil war.

Great Books on La Violencia in Guatemala.

Virginia Garrard-Burnett on La Violencia in Guatemala.

![]()