By Samuel Ginsburg

Marfa, a West Texas town of less than 2,000 permanent residents, attracts a lot of visitors. Known as the backdrop to 1959 James Dean film Giant, the town’s main attractions include two main streets lined with galleries, the mysterious Marfa lights that only seem to come out when nobody is looking, and the Chinati Foundation, an epic former military base-turned-art museum. While the scene is now speckled with luxury airstreams and Instagram models dressed in pristine cowboy gear, the bohemian vibe brought over in the 1970s by artists trying to escape New York still resonates, and the sprawling desert backdrop adds to the effect that makes “Marfa” (the idea) feel bigger than Marfa (the place).

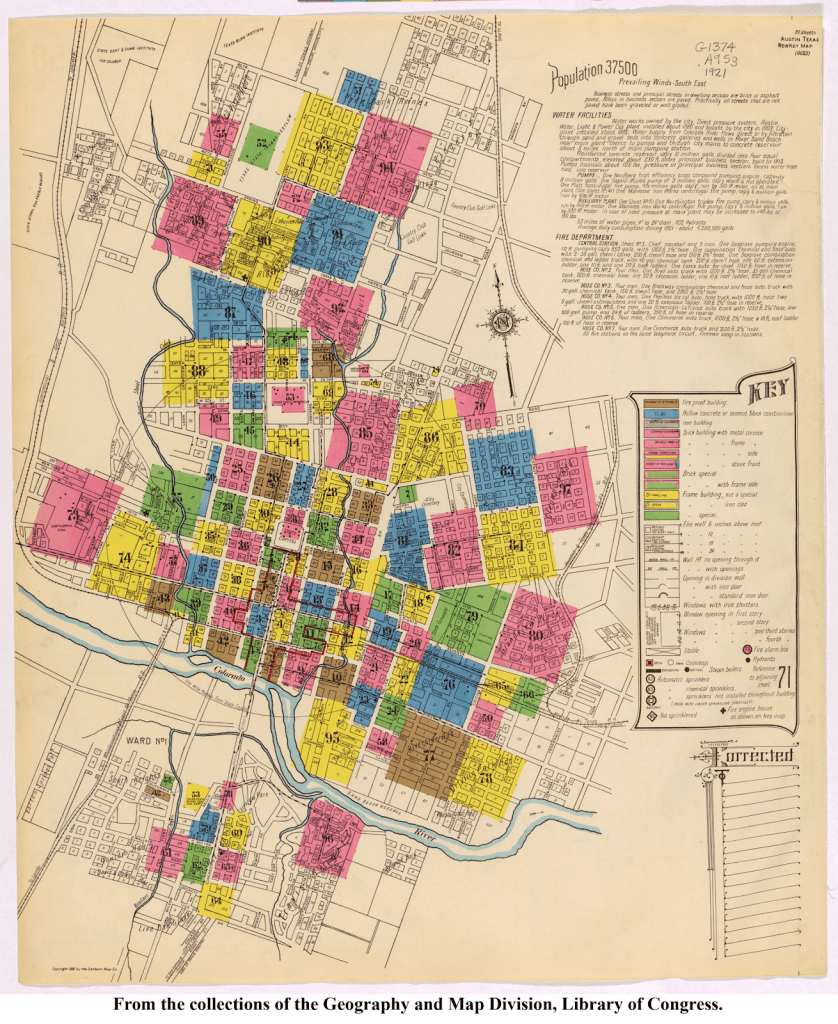

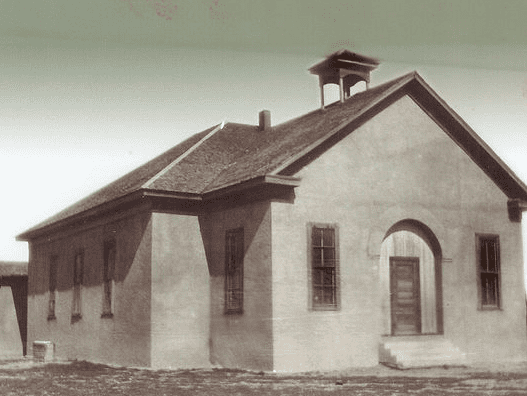

Just a few blocks from the main drag is the Blackwell School, a plain, white building that might have gone unnoticed if it weren’t for its Texas Historic Landmark sign. The museum inside the old schoolhouse tells the story of de facto segregation in Marfa since 1889, as special schools were set up for Mexican-descendent children until integration was achieved in 1965. Old desks and books line the open rooms, along with photos and articles about the scholarly and extracurricular activities of the students. More than a look at the evils of segregation and inequality, the museum highlights the special moments in the lives of the people that passed through the school. Photographs show smiling children decorating pumpkins, playing basketball, and proudly posing in marching band uniforms. While meandering through the exhibits, one gets the feeling that great things happened in this place, despite problematic history that led to the school’s founding.

As not to cover up the issues surrounding the school, there are parts of the museum that show the instances of institutional discrimination, such as the board of former teachers that features very few Spanish last names. The museum’s most striking exhibit is titled “Burying Mr. Spanish” and tells the story of a mock funeral that was held in 1954 to officially kill off the use of Spanish at the school. As English was the only language allowed on campus, 7th-grade teacher Evelyn Davis organized an event in which students wrote Spanish words on small pieces of paper, put them in a coffin, and then buried them next to the school’s flagpole. The museum has photos of the event, along with the coffin and a wooden cross that says “Spanish” and “R.I.P.” In “The Last Rights of Spanish Speaking,” Davis calls hearing the language her greatest “pet peeve,” and recounted the ceremony that had been going well (for her) until the very end: “Everything was perfect up to this moment until two pall bearers, who had not rehearsed, were to lower the casket with dignity. They started pulling against each other in disagreement, which was followed by anger, and then a volley Spanish curse words # % @ * $ * ? The solemnity turned to titters, then giggles followed by hilarious laughter as the bearers threw dirt at each other. What a GREAT FIASCO!” As heartbreaking as it is to read about a school-sanctioned ceremony aimed at cutting off the students’ cultural heritage, it’s hard not to laugh at the ensuing bout of rebellious chaos. As a moment of both forced assimilation and student resistance, this scene recognizes the complicated nature of this space and the need to preserve its stories.

The Blackwell School Alliance was founded in 2007 by former students as the abandoned building was being threatened with demolition. Since then, efforts have been made to seek state and federal protection of the site. The alliance has also looked for ways to reincorporate the school’s history back into the public memory of Marfa. These efforts included the Blackwell Block Party and the commission of a mural by artist Jesus “Cimi” Alvarado. The mural features a poem by Luis Valdez about Chicano pride, an image of current Marfa students building rockets, and the West Texas desert in the background. Most importantly, the mural positions the Blackwell School in the very center, right between Marfa’s iconic water tower and Presidio Country Courthouse. The goal is to reshape how Marfa is seen by both tourists and residents, to create a space for this history within the conceptual landscape of artists and cowboys. For those people fighting to keep the museum open and running, this is a part of Marfa that more people should be visiting.

For more information on the museum and for ways to support the Blackwell School Alliance, visit //www.theblackwellschool.org/.

You May Also Like:

From Marfa to Mauritania in Forty Years

A Longhorn’s Life Service

History Revealed in Small Places

The views and opinions expressed in this article or video are those of the individual author(s) or presenter(s) and do not necessarily reflect the policy or views of the editors at Not Even Past, the UT Department of History, the University of Texas at Austin, or the UT System Board of Regents. Not Even Past is an online public history magazine rather than a peer-reviewed academic journal. While we make efforts to ensure that factual information in articles was obtained from reliable sources, Not Even Past is not responsible for any errors or omissions.