The powerful myth of ‘American exceptionalism’ would have us think that the United States alone offered the world universal ideals of democracy, self-determination, and shared prosperity. However, if we open our eyes beyond canonical nineteenth-century writers such as Alexis de Tocqueville, an alternate story emerges. The long-ignored yet staggering number of works by publicists, historians, geographers, novelists, economists, and jurists from Caracas, Bogotá, Santiago de Chile, Buenos Aires, Mexico, Quito, and Lima begin to reveal the remarkable dimensions of modern republican experiments in Spanish America. Early republican experiments in Spanish America occurred at a time when there were no models to follow. While republicans in Europe battled monarchists and the clerical old regime, while they increasingly imagined their republics as colonial empires of racial inferiors, and while republicans like Thomas Jefferson and James Madison in the United States built their republic on white supremacy and industrialized slavery in cotton plantations, a generation of Spanish American sociologists, economists, anthropologists, and political philosophers became the world’s republican vanguard.

Early republican experiments in Spanish America occurred at a time when there were no models to follow. While republicans in Europe battled monarchists and the clerical old regime, while they increasingly imagined their republics as colonial empires of racial inferiors, and while republicans like Thomas Jefferson and James Madison in the United States built their republic on white supremacy and industrialized slavery in cotton plantations, a generation of Spanish American sociologists, economists, anthropologists, and political philosophers became the world’s republican vanguard.

One of their most resilient inventions was rhetorical. Spanish Americans consistently portrayed the period of Spanish rule as obscurantist, tyrannical, and corrupt. This discourse of Latin America’s “colonial legacies” is pervasive today. During the early nineteenth century, Spanish Americans invented distinct “colonial legacies” to legitimize their intellectual and political work in rejecting Spanish rule. They believed science could diagnose, treat, and excise those pernicious colonial legacies. Their radical new form of political modernity required they take a systematic approach to understanding and changing their society, their economic structures, and their political processes. As perceived obstructions changed over time, so did proposed solutions, which in turn contributed to the invention of new philosophies, anthropologies, sociologies, geographies, and sciences.

The case of a little-known Colombian jurist and writer, José María Samper, illustrates this creative process. Samper posed hard questions to both Europeans and U.S. Americans as he wrote about the history of Colombia while traveling through Europe from 1858 to 1862 with his newly wedded wife, Soledad Acosta de Samper. With so many innovative studies by Spanish Americans available, Samper wondered why Europe remained deaf to the socio-political complexity and innovation of Spanish America. He knew the unfortunate answer: the confounding noise produced by the political storms that crashed through Spanish America during the first half of the nineteenth century. Narratives about chaos, violence, and caudillos drowned out any discussion about how these republics were experimenting with democracy, sovereignty, universal male suffrage, republican equity, and self-determination.

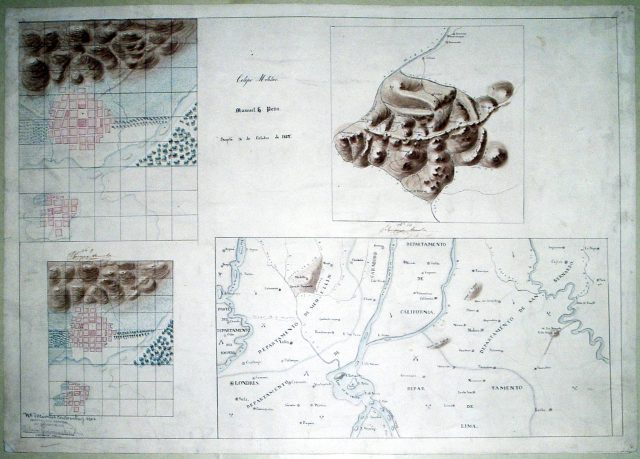

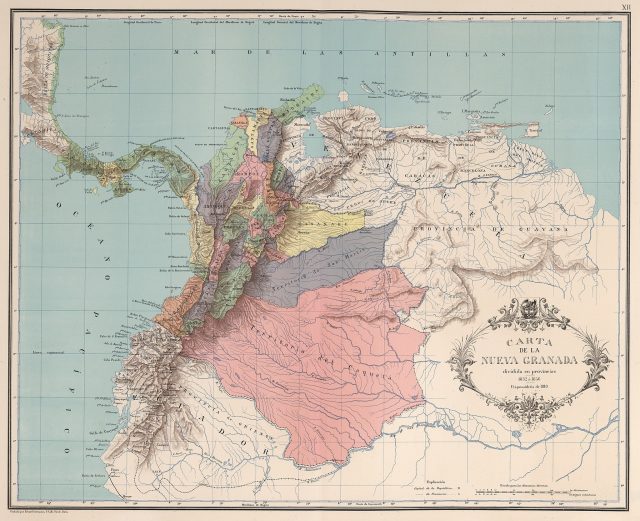

Map of Nueva Granada, 1832-1855 (Carta XII del Atlas geográfico e histórico de la República de Colombia, 1890. Wikipedia)

Samper represented a generation who creatively re-imagined republicanism for New Granada (a polity that encompassed roughly today’s Colombia and Panama). He, along with hundreds of other men in the emerging republic, formed the Caldas Institute (Instituto Caldas) in the late 1840s. This scientific society crossed the political spectrum and championed a circulatory ideal for New Granada. The circulation of people, goods, and ideas would undo the supposed Spanish colonial legacy of fragmentation and exploitation of territories that led to stagnation and poverty locally. Rather than foment export-led growth on the backs of enslaved people, a range of government officials from an array of provinces instead focused on identifying and strengthening the internal circulation of goods and services. Provincial chapters quickly formed and worked to identify what industries needed improving, how to ensure proper morality, and where infrastructure needed to be built. Circulation of people, goods, ideas, and credit was further supported by steamship navigation along the Magdalena River flowing through the newly created Puerto Colombia in Barranquilla, a port intended not just for export but also internal circulation among New Granada provinces.

Caldas Institute members also helped identify the brightest minds from the provinces. Those young men won scholarships to attend New Granada’s military school in Bogotá. Cadets learned new mapping techniques from foreign experts through apprenticeship. As revealed by the fanciful imaginary landscape drawn by sixteen-year-old Manuel Peña, cadets learned to express the implications of local and global circulation for the Republic. Consider how Peña’s map drew together California, London, Lima, and Carabobo, along with existing New Granada cities and towns such as Medellin, Socorro, Vélez, Oiba, and Cajicá. All these places, according to Peña’s cartographic imaginary, also participated in a war for liberation as signaled by crossed swords strewn throughout the territory.

The ideal of free circulation to combat a colonial legacy of fragmentation, exploitation, and economic stagnation helps us better understand why early republicans in New Granada not only moved towards the abolition of slavery by 1851, but also worked tirelessly towards identifying the best routes for canals and roads. The circulation of free people, ideas, and trade required infrastructure that could traverse the Andean mountainous terrain, after all. The Chorographic Commission, first conceptualized by members of the Caldas Institute, was to bring to fruition New Granada’s long-term development projects. The work this scientific expedition carried out from the 1850s through the 1860s was deeply entwined with the development of a republican political ideology based on the abolition of slavery and experimentation with universal male suffrage.

Agustín Codazzi of the Chorographic Commission camping with his collaborators in Yarumito, Soto Province (1850, Biblioteca Nacional de Colombia, Colección Comisión Corográfica. Wikipedia).

While some Caldas Institute members engaged in such remarkable experiments with republican circulation, others experimented with what José María Samper termed the science of constitutionalism. Their work culminated in the constitution of 1853, which was radically democratic even by today’s standards. No electoral college would get in the way of the will of the people. In the wake of slavery’s abolition, presidents were directly elected through universal male suffrage, as were all representatives of Congress, members of the Supreme Court, and provincial governors. The 1853 constitution also permitted the provinces of New Granada to develop their own charters, and a flurry of constitution writing ensued. The most remarkable of these was that of Vélez, which granted universal suffrage to women as well as men. The 1853 constitution proved such a radical re-working of the democratic system that Civil War broke out. The devastation was overwhelming. An alternate constitutional plan emerged, also led by José María Samper, that vested sovereignty in the states rather than individuals. These were the kinds of constitutional experiments Samper and his cohort shared with the world.

Spanish Americans have too often been simplified as either detached racist elites with little knowledge of local realities looking only to profit from export led growth at any cost, or violent anti-democratic caudillos. De-exoticizing Spanish American thinkers allows us to take their early republican projects – and their discontents– seriously.

Highlighting the nineteenth-century invention of colonial legacies also allows us to begin to question why thinkers, writers, scholars, and educators in the United States, in the wake of independence, did not create the category of colonial legacies for themselves. Why did they not identify legacies of British rule that needed to be rooted out in order to produce a republic of equal citizens, no matter their race? Why, indeed, can we see colonial legacies so easily for Spanish America, but we have such a hard time identifying the persistent colonial legacies that continue to make universal democracy and shared prosperity in the United States so difficult to achieve?

Lina del Castillo, Crafting a Republic for the World: Scientific, Geographic, and Historiographic Inventions of Colombia (2018)

Further Reading:

James Sanders, The Vanguard of the Atlantic World: Creating Modernity, Nation, and Democracy in Nineteenth-Century Latin America (2014).

Sanders underscores how republicans in Colombia and Mexico, but also other republics such as Chile, Uruguay, and Venezuela, saw themselves as shaping political modernity in the world.

Nancy Appelbaum, Mapping the Country of Regions: The Chorographic Commission of Nineteenth-Century Colombia (2016). This focused study on the Chorographic Commission in Colombia reveals the richness and complexity of that state-sponsored scientific expedition.

Mauricio Tenorio-Trillo, Latin America: The Allure and Power of an Idea (2017).

Tenorio-Trillo offers a short essay on why the idea of Latin America has proved remarkably resilient since the mid-nineteenth century.

Hilda Sabato, Republics of the New World: The Revolutionary Political Experiment in Nineteenth-Century Latin America ( 2018).

Sabato’s book effectively describes the fundamental innovation of Latin American politics in the nineteenth century as the revolutionary decision to adopt popular sovereignty as the founding principle of the polity and as the only source of legitimate power.

José M. Samper, Ensayo sobre las revoluciones políticas y la condición social de las repúblicas Colombianas (Hispano-Americanas); con un apéndice sobre la orografía y la población de la Confederación Granadina (1861/2018).

Top image: Watercolors by Manuel María Paz, a member of the Chorographic Commission: A Bridge on the Ingara River (L), The Village of Tebada (M), The Square of Quibdo (R), Chocó Province (World Digital Library).