On Saturday, September 21, 2024, I had the privilege of joining a diverse group from Austin’s activist community for a workshop, Archiving Activism Freedom School, organized by Dr. Ashanté Reese and Dr. Ashley Farmer–both of them Associate Professors of African and African Diaspora Studies (AADS) at the University of Texas at Austin. Funded by the National Archives’ National Historical Publications and Records Commission, Campus Contexutation Intiative, and GRIDS, the workshop aimed to make community archiving practices and techniques accessible with the wider goal of documenting activism. The purpose of the Archiving Activism: Freedom School was to “teach student activist, organizers, and community organizations how to archive their community work and maintain digital documentation of their legacies”.

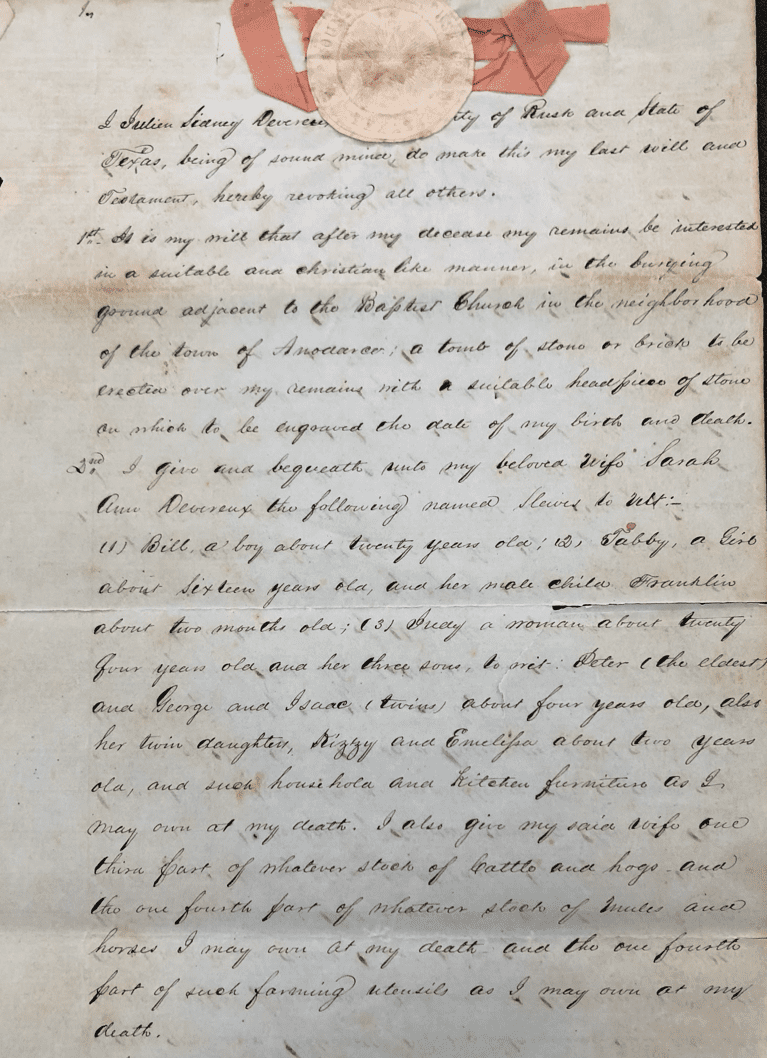

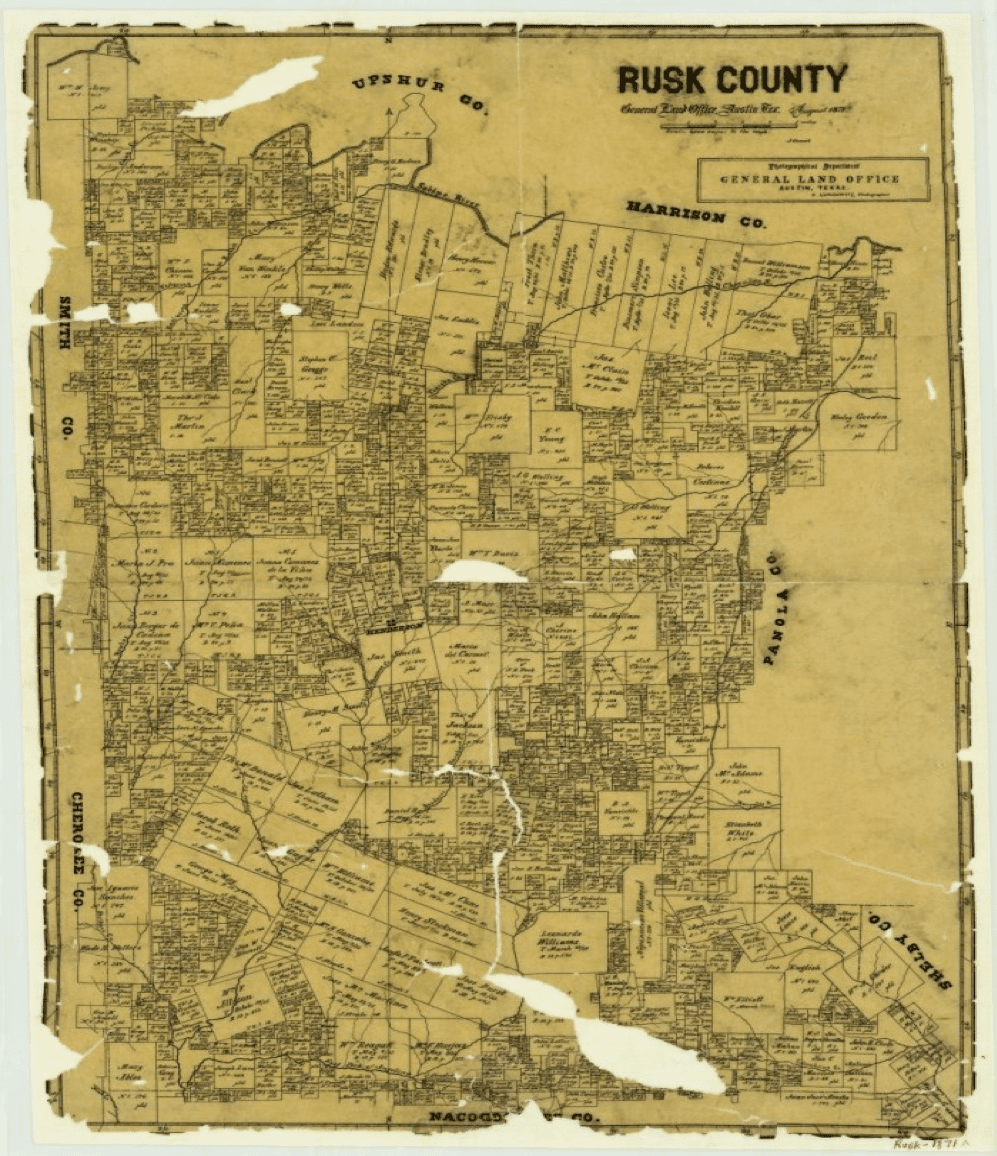

Oriented towards minority student activism and focused on the diverse racial geographies of Austin, the Archiving Activism Freedom School was “organized in the spirit and tradition of historical freedom schools”. As the organizers explain, Freedom schools “are temporary, alterative, and free schools aimed to help organize communities for social, political, and economic equality”. They have their origins in 18th and 19th century secret schools, “where enslaved people learned to read, write, and become politically engaged”. Such institutions became key tools for labor movement and civil rights struggles through the 20th century.

Historically, the purpose of freedom schools has been to empower communities by teaching their history, critically examining their current circumstances, and fostering education for social and political transformation. These goals were thoughtfully integrated into the Archiving Activism Freedom School.

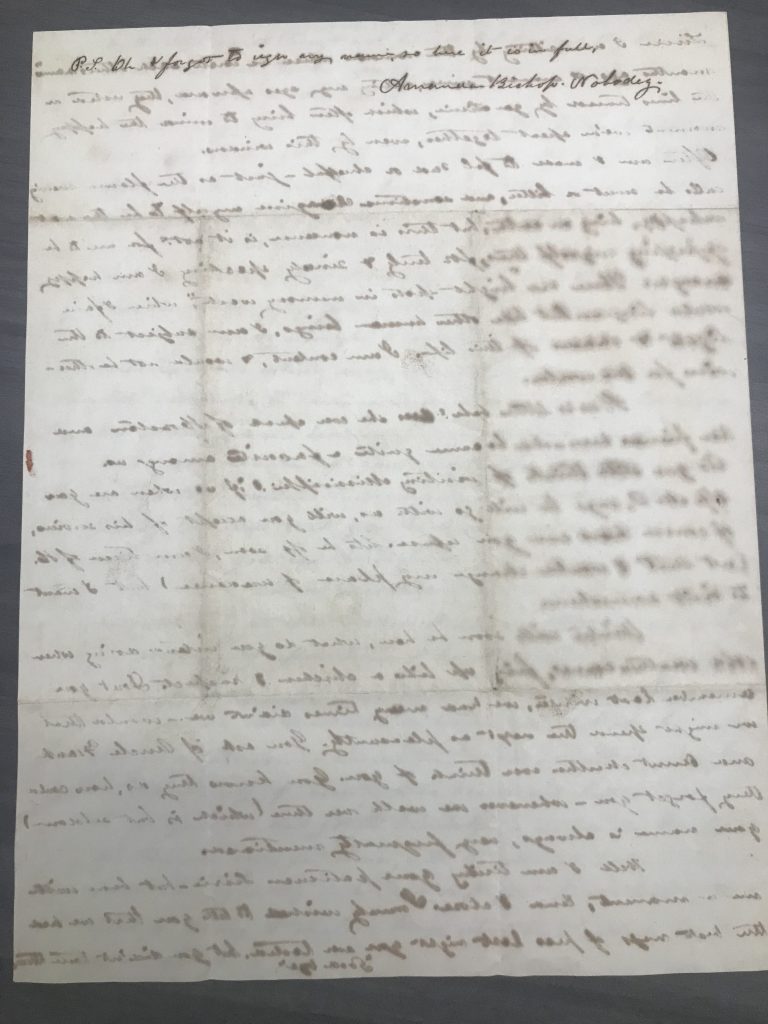

The first session of the agenda began with two talks by Texas-community members that focused on the question of ‘Why archives matter for your activism’. Jonathan Cortez, (Assistant Professor at the History Department of UT Austin) gave a talk on their experience with the Vicente Carranza Archive which was collected by a Chicano radio host from Corpus Christi. Cortez’s experience as a researcher brought them together with Vicente Carranza, resulting in the development of the Vicente Carranza Papers, a Texas A&M University-Corpus Christi (TAMU-CC) Special Collections now available for consultation at TARO (Texas Archival Resources Online). Cortez’s talk highlighted the importance of community history and creative thinking for archival practice as a means to highlight the activism of Hispanic communities in South Texas.

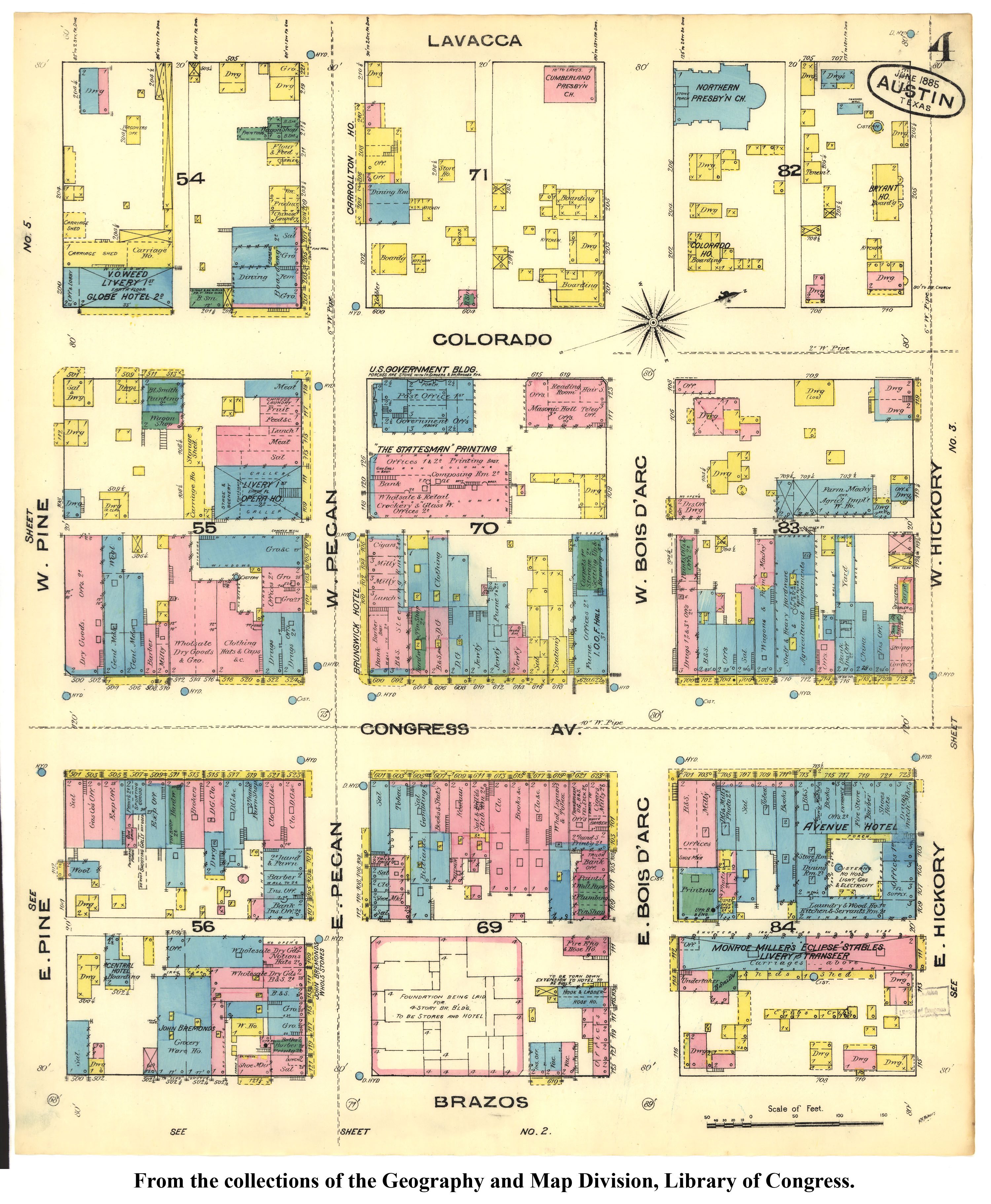

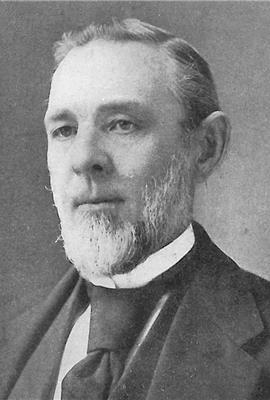

In the second presentation, Stephanie Lang, writer, organizer, community curator, and founder of RECLAIM, an organization that discovers, recovers, and showcases narratives and histories of Black people through the diaspora, shared her experience with the changing racial landscape of Austin. A seventh-generation African American woman from Austin, she talked about the importance of oral history for documenting the Black history of Austin. Lang emphasized that preservation is a way to maintain the memory and presence of the people of East Austin, one of the city’s most rapidly gentrifying neighborhoods in the city. Archiving, Lang stressed, offers proof that black and brown communities of Austin have pushed back.

In a subsequent session focused on the question of “Who deserves to hold your archives?”, participants heard from Carol Mead (Head of Archives and Manuscripts at The Dolph Briscoe Center for American History), Jacqueline Smith-Francis (Archivist and Curator of Black and African American stories at the Austin History Center), and Rachel Winston (Austin-Based activist, curator, and archivist, currently holding the inaugural Black Diaspora Archivist position at LLILAS Benson, Latin American Studies and Collections).

A long-time archivist at the largest archive within the University of Texas system Mead’s presentation highlighted the ethics of archiving. In doing so, she stressed questions of access and use to keep in mind while creating and engaging with archives. Smith-Francis emphasized that archival work is deeply connected to land, sovereignty, and the silences contained within archives. Drawing on her 25 years as an archivist at the Austin Public Library, she talked about how community archive programs in Austin have contributed to the decolonization of archives. This shift means that archival initiatives now prioritize diverse subjects, stories, and collections—largely thanks to efforts like her own. Finally, Rachel Winston’s presentation offered valuable insights into the decision-making process behind where to place collections and why. She emphasized the importance of carefully selecting who you engage with when creating archives and shared key strategies for building meaningful relationships with archival institutions.

The second half of the workshop was focused on creating an archival plan. First, archivist Genevia Chamblee-Smith, Hidden Collections Curator at the Texas State University Libraries, walked participants through the step-by-step process needed to create an archive. She outlined six key steps: 1) identify, 2) evaluate, 3) describe, 4) arrange, 5) preserve, and 6) name. In the spirit of sharing knowledge, I will briefly outline the main points of these key steps.

- Identify: Take inventory of the materials. What is available? What is important to keep, and what can be discarded? Where are the materials located?

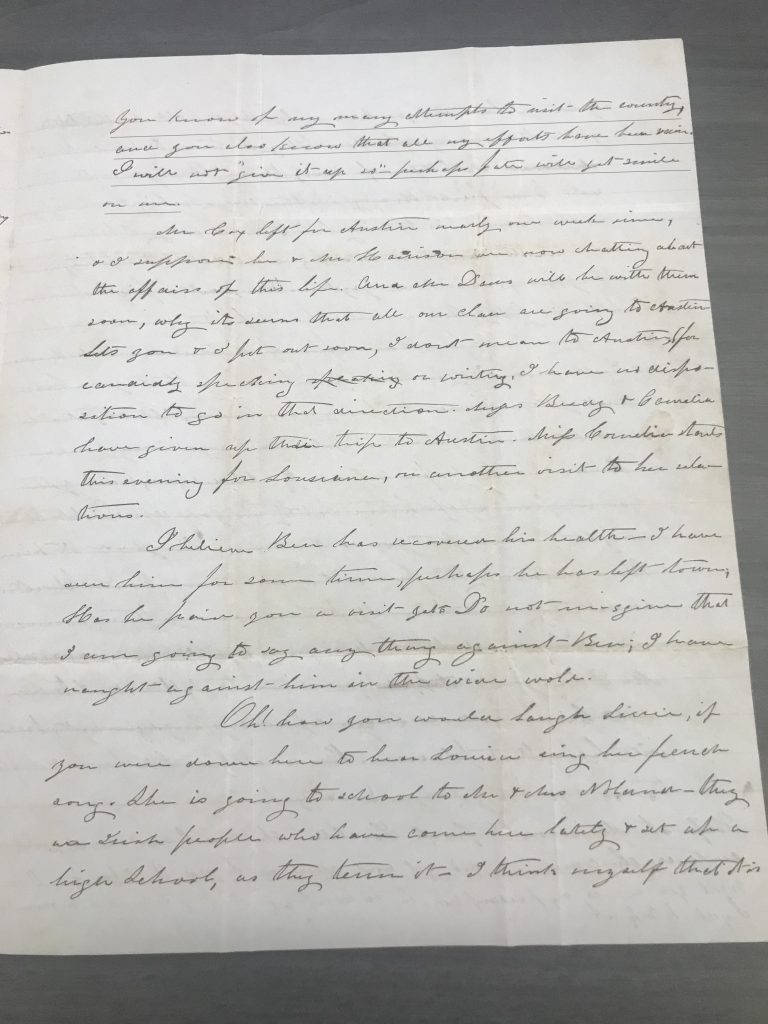

- Evaluate: Assess the types of materials you have. Which items are the most sensitive or vulnerable? Do you need professional assistance to process or preserve them?

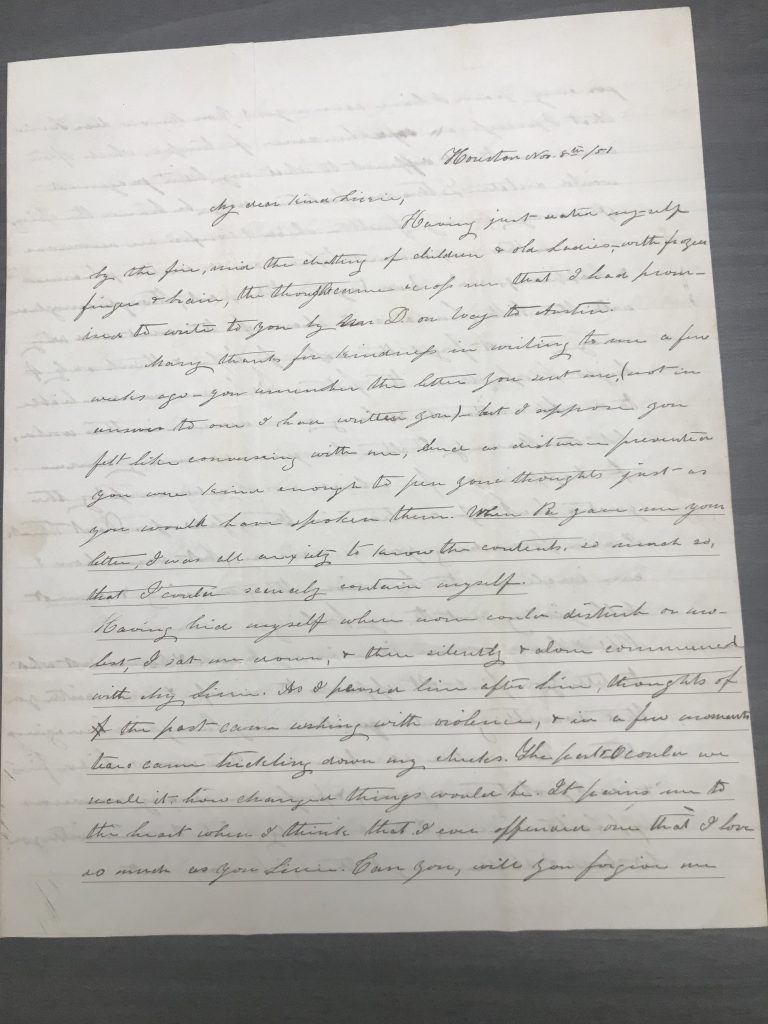

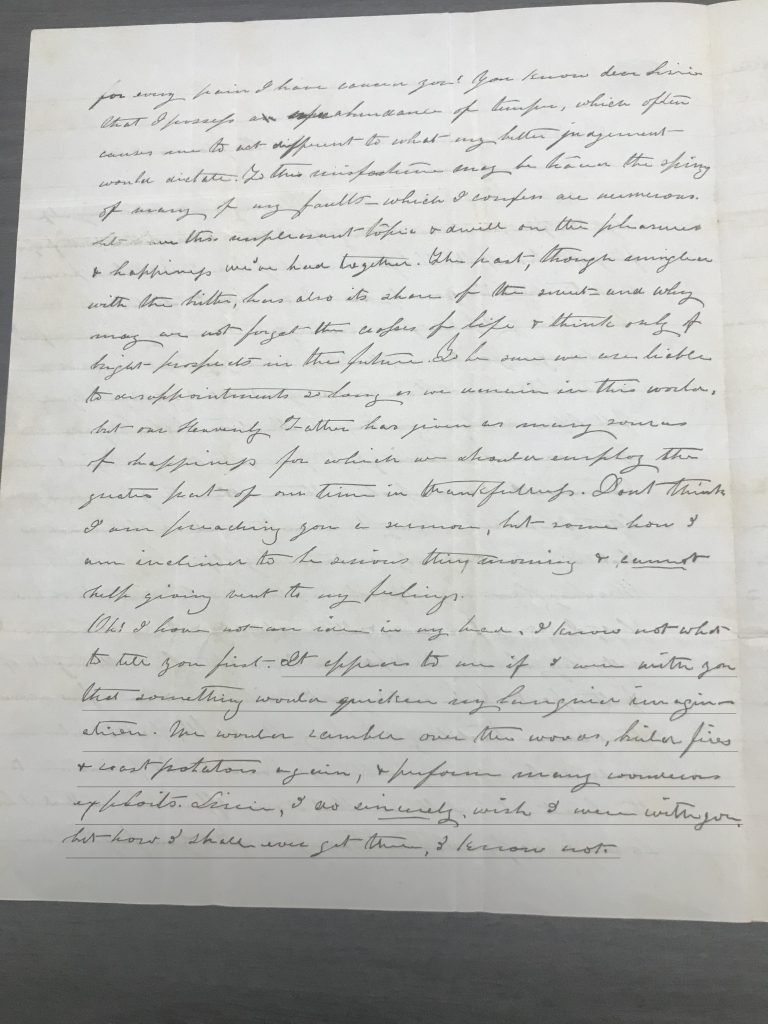

- Describe: Each item intended for preservation must be described in detail, answering key questions: What is it? Why is it significant? Who created it? Where did it come from?

- Arrange: Organize materials by subject or type. Create an inventory for easy reference, and store documents in acid-free boxes or folders. Ensure the arrangement allows others to access the materials easily.

- Preservation: The workshop emphasized digital preservation techniques. Staying current with technology is essential to prevent materials from becoming obsolete. Key strategies include scanning, converting to digital files, storing data across multiple external drives, and regularly backing up materials.

- Name: The final step is consistent file naming. Use the File Naming Convention (FNC) framework to ensure files are easy to identify and relate to others. File names should include relevant metadata, avoid spaces and special characters, follow naming conventions, and be descriptive.

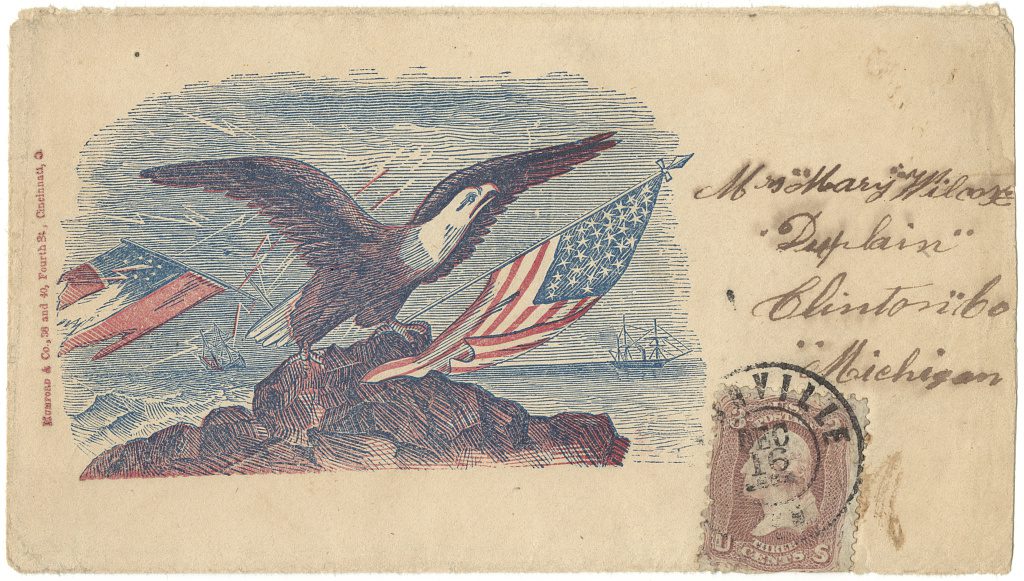

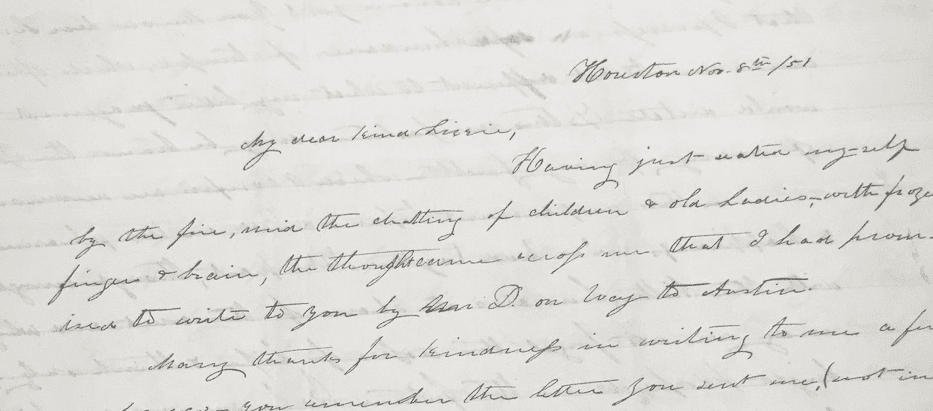

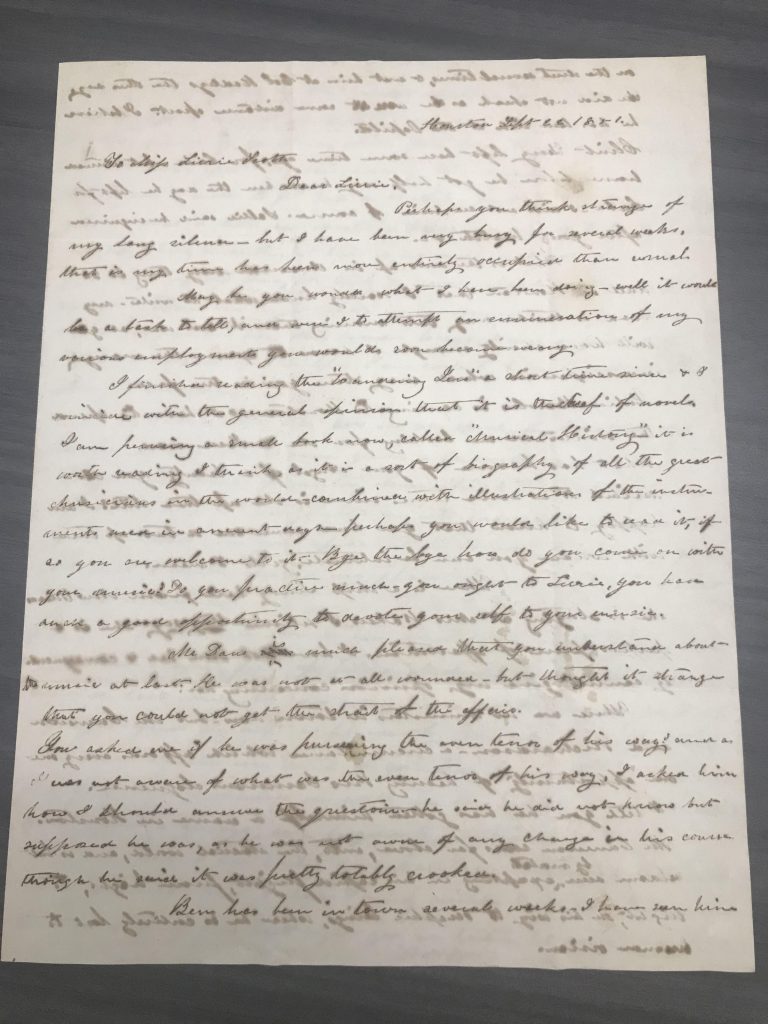

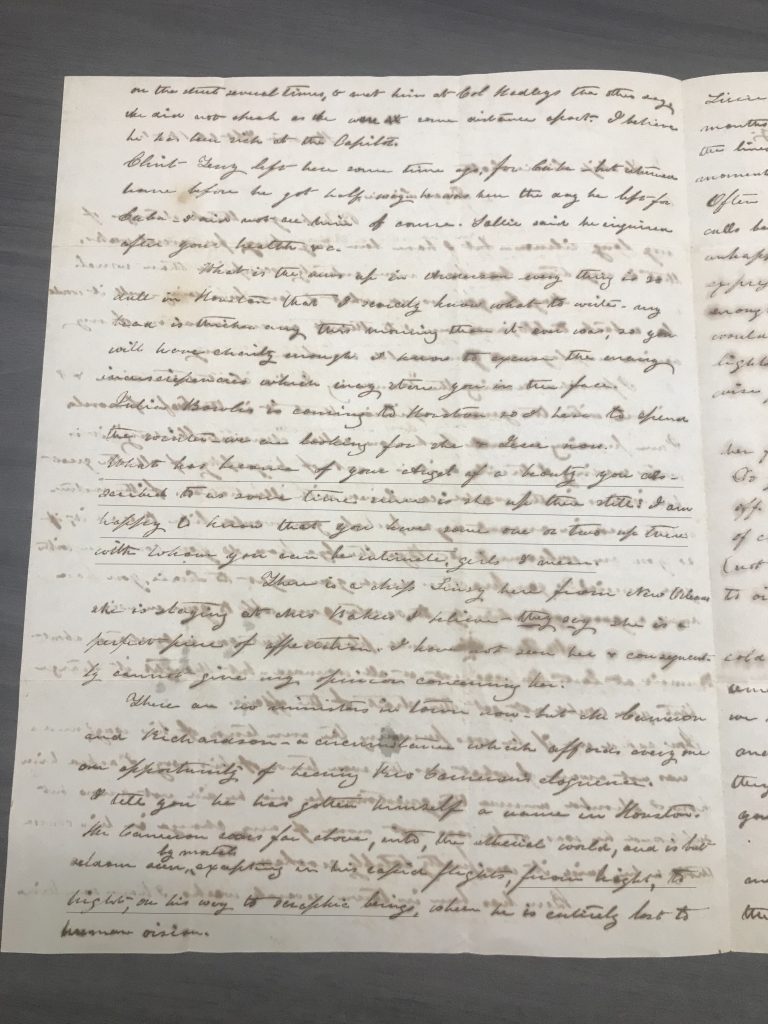

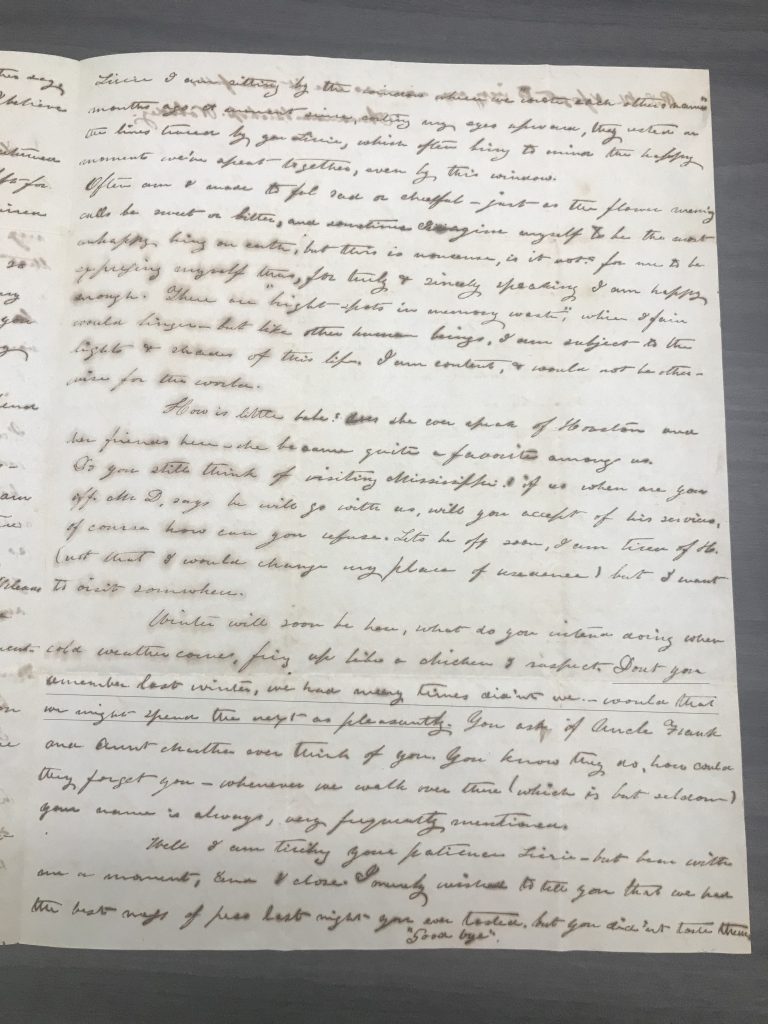

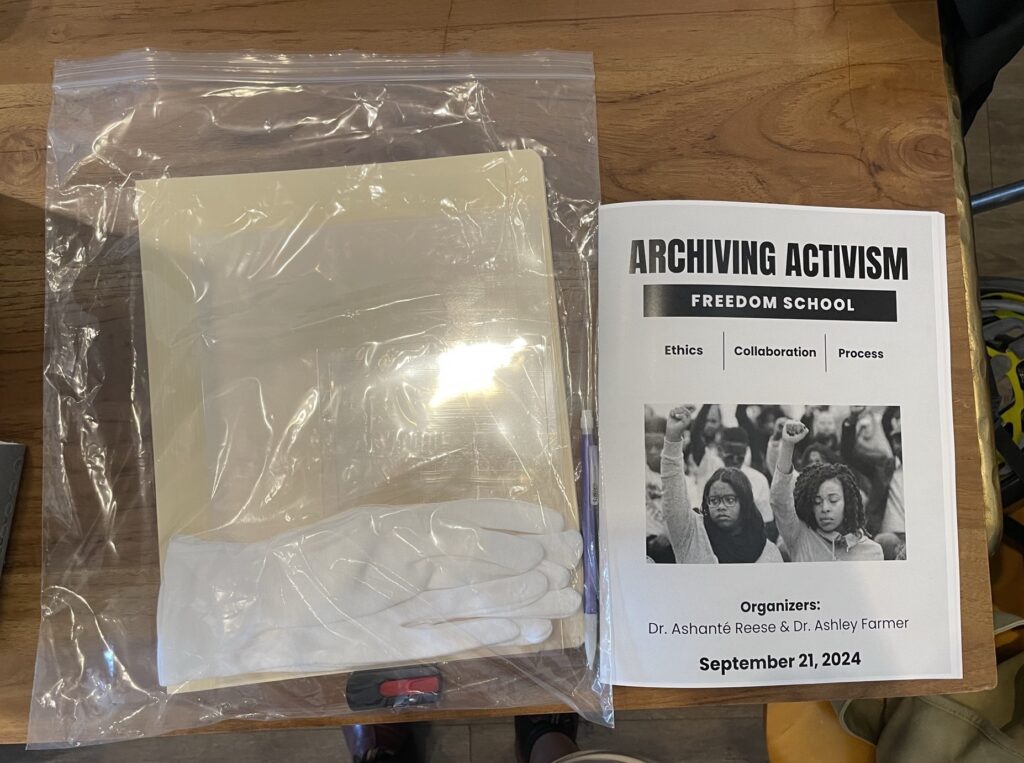

With all this information at hand, the Freedom School ended with a digitization workshop where participants were able to scan and organize their materials for digitization, aiming at social movements preservation.

The workshop included concrete items designed to help with archiving work. Participants received an acid-free archive box containing cotton gloves, a pencil, a flash drive, and an acid-free folder. We also received a booklet that not only outlined the day’s agenda but also provided space to brainstorm and map out the six key steps for organizing our archiving projects.

The Archiving Activism Freedom School was an inspiring initiative, designed to introduce non-trained archivists and community participants to the process of creating archives. I spoke with several attendees focused on activism. They were genuinely excited to be there and grateful for the opportunity to learn more about how to archive community’s materials in a professional, intentional way.

More importantly, this workshop serves as a much-needed example of how to bridge the gap between archivists, academics, and activists. While the concept of community archives is gaining momentum, the scholarship in this field is still emerging. This workshop offered invaluable insights into the priorities, challenges, and opportunities that community archives present, making it an incredible learning experience for all involved.

Camila Ordorica is a doctoral candidate in Latin American History at the University of Texas at Austin, where she studies the history of the General Archive of Mexico during the long nineteenth century (1790-1910). Her research dialogues with archival, cultural, social, and material history, and explores how archives are written into history and their role within it. Camila’s passion for archival studies is rooted in her training as an archivist. She has worked at the Acervos Históricos de la Universidad Iberoamericana and the archives of Sine-Comunarr. She has also collaborated with UNAM’s ENES-Morelia, the ’17, Institute of Critical Studies’ and the International Federation of Public History in archival studies, practice, and digital humanities.

The views and opinions expressed in this article or video are those of the individual author(s) or presenter(s) and do not necessarily reflect the policy or views of the editors at Not Even Past, the UT Department of History, the University of Texas at Austin, or the UT System Board of Regents. Not Even Past is an online public history magazine rather than a peer-reviewed academic journal. While we make efforts to ensure that factual information in articles was obtained from reliable sources, Not Even Past is not responsible for any errors or omissions.