This essay was written as part of Dr. Jorge Cañizares-Esguerra’s course, Colonial Latin America. Hope Payton explores how Indigenous and African women—both free and enslaved—navigated the legal, economic, and religious institutions of colonial Latin American cities. Drawing on wills from Potosí and La Plata and a freedom suit from Lima, it examines how these women accumulated property, engaged with paperwork culture, and leveraged church tribunals to assert their rights. In doing so, the essay sheds light on the appeal of Catholicism in the Spanish Indies, particularly its role as a mediator of protection, legitimacy, and social mobility for marginalized communities.

The conventional narrative of Spanish colonization in the Americas typically portrays Indigenous and African peoples as passive recipients of European conquest and conversion. This perspective, however, overlooks the agency of these groups in shaping colonial society. In cities like Potosí—major economic centers of the Spanish Empire—free and enslaved indigenous and African people found opportunities to accumulate wealth, property, and legal knowledge. Contrary to the assumption that indigenous people were always relocated to cities by force or compulsion, many indigenous groups strategically used urbanization to consolidate power and to maintain authority within their own ethnic groups; securing leadership, controlling labor, and engaging in the colonial economy while preserving traditional structures—demonstrating their agency in shaping their own futures.

Despite their rigid social hierarchies, cities in the Spanish Empire allowed for certain flexibility that indigenous and African people, especially women, could exploit. Economic opportunities, particularly in large industrial cities like Potosí, created avenues for wealth accumulation, while the Catholic Church’s legal structures provided mechanisms for securing assets and negotiating social standing. Through participation in the marketplace, property ownership, and engagement with notarial culture, women actively shaped their own economic futures.

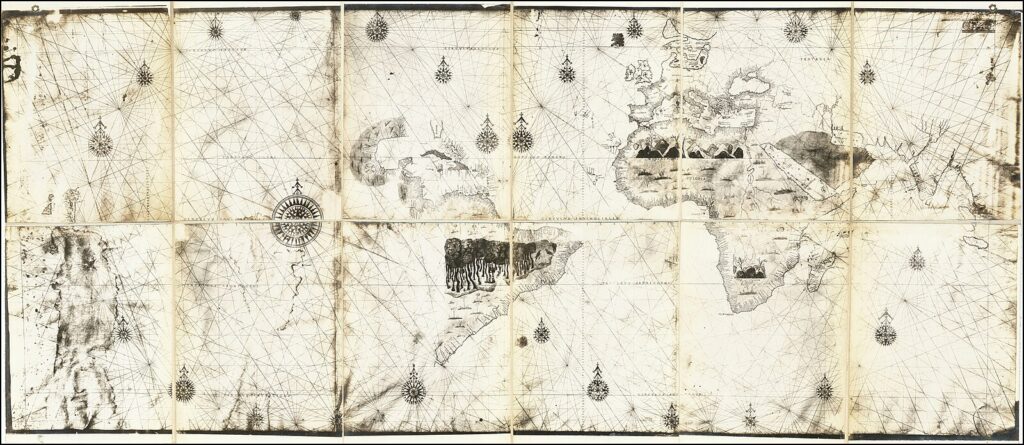

Source: Wikimedia Commons.

At the same time, the Church’s bottom-up structure, reinforced by extensive bureaucratic systems and opportunities for petitioning, allowed marginalized groups to access legal protections and assert their rights. Church tribunals provided an alternative to colonial civil courts, allowing commoners, enslaved individuals, and indigenous peoples to challenge injustices and seek legal remedies. This accessibility contributed to Catholicism’s widespread appeal and deep entrenchment in colonial society. Indigenous and African women in colonial Spanish America exercised agency by leveraging urban economies, church legal structures, and Catholic institutions to accumulate wealth, secure property rights, access legal recourse, and shape both their personal and communal identities within the Catholic Church and the Spanish colonial system.

Cities in colonial Spanish America, particularly those like Potosí and La Plata, provided indigenous and African women with unique opportunities to accumulate wealth, property, and legal knowledge. Unlike rural areas, where economic mobility was more restricted, urban environments fostered commercial activity, offering women access to markets, trade networks, and financial transactions that could increase their economic standing. Cities also housed notarial offices and church institutions, which played a crucial role in recording contracts, wills, and property transactions. Through engagement with these legal and bureaucratic systems, women learned to navigate paperwork, ensuring that their assets were protected and transferred to future generations.

Cities as Sites of Agency

The will of Luisa de Villalobos, a free Black woman who migrated from Nombre de Dios in Panama to Lima and later Potosí, exemplifies how cities enabled women to accumulate wealth through diverse commercial ventures in cities. Villalobos, who drafted the will in 1577, trafficked and had investments in fine European clothing, perfumes, and silver. Villalobos left a considerable amount of her wealth to two other Black women, Francisca Godines and Maria Fula, declaring “that to Francisca Godines or her closest heirs [you] pay the value of nine glass bottles of orange blossom water and thirteen flasks of the said water” and “that one yellow skirt with velvet trim, another trimmed with velvet, one doublet of fine wool and one wool cloth in which it is wrapped belongs to Costanca, morena, of the falconer of the Villa Real.”[1] By drafting a will in 1577, Villalobos ensured the legal recognition of her property and debts while also making strategic donations or sales to other free Black or enslaved Black women that enabled them to accumulate wealth and property as well.

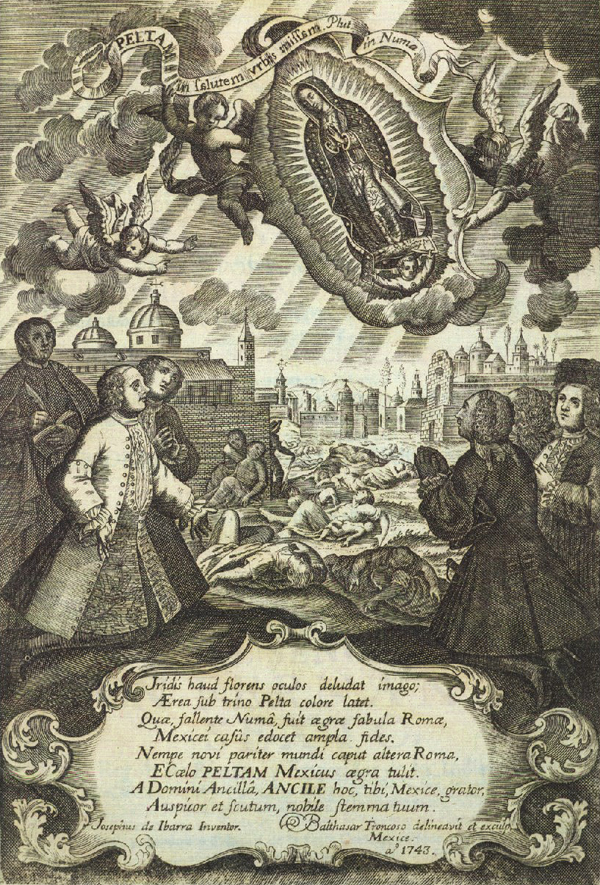

Source: Wikimedia Commons.

Cities in colonial Spanish America were also home to cofradías, religious brotherhoods, that provided monetary support to enslaved individuals so they could purchase their freedom. These organizations were supported by the church and its administrators, such as the Jesuits. Villalobos supported cofradías by leaving a portion of her wealth to a Jesuit priest, Father Medina. In her will, she states that she has “in the possession of María Fula” a large number of expensive European textiles and that it is her “will that with all of this Father Medina does what he likes.” This donation to the Jesuit priest likely supported cofradías in Potosí, thereby reinforcing the economic and legal networks that benefited marginalized groups in urban centers.

Similarly, the will and codicil of doña Isabel del Benino, a free indigenous woman, drafted in 1601, show how urban economies enabled indigenous women to accumulate wealth. She owned a rural estate near Potosí and conducted agricultural business with clerics in Potosí, such as “Father Joseph de Llanos, priest and vicar of this valley” whom she stated in her will owed her “a remainder of thirty pesos from some goats that I sold him.”[2] Through her business with the clerics, she was able to accumulate wealth. In her will, she also leaves her remaining estate to her daughter, “my hija natural, doña María del Benino, whom I leave for my universal heir in all the remainder of my estate.” This statement in Benino’s will demonstrates yet another way cities and their legal framework allowed women to accumulate wealth and property, through knowledge of paperwork and the property rights granted to women in cities. Despite some racial and gendered restrictions, urban centers provided economic and legal opportunities that allowed African and Indigenous women to secure wealth and navigate the colonial system to their advantage.

The Church as a Legal Resource

The accessibility of church tribunals to commoners, enslaved individuals, and indigenous people played a crucial role in the widespread appeal of Catholicism in colonial Spanish America. Unlike civil courts, which often favored colonial elites and upheld rigid social hierarchies, ecclesiastical courts provided marginalized individuals with an alternative avenue for seeking justice. The Church’s willingness to hear petitions from society’s most vulnerable reinforced its image as the moral authority that protected the faithful and the followers, fostering loyalty and devotion among indigenous and African populations. By framing grievances in religious terms, petitioners could align themselves with the Church’s broader mission of upholding Christian values, further legitimizing Catholicism’s role in daily life.

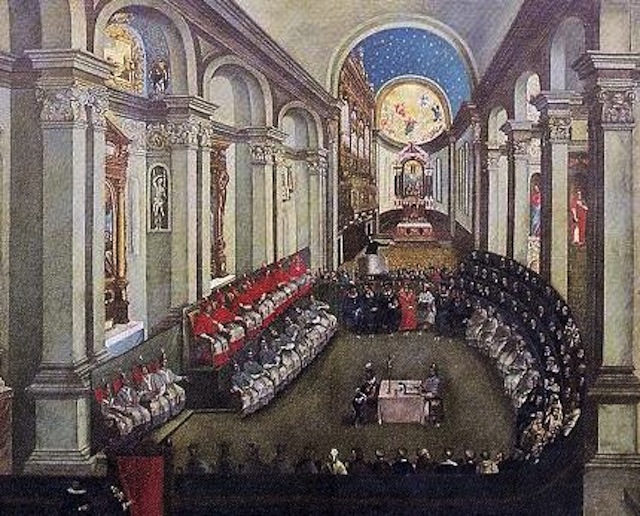

Source: Wikimedia Commons

The lawsuit filed by Natividad, an enslaved woman in Lima, against her master Doctor don Juan de la Reinaga in 1792, focused on his sexual abuse against her, exemplifies how church tribunals provided enslaved individuals with a means of contesting their mistreatment. In her petition, Natividad requested her freedom, telling the judge, who is a member of the Church, “Your superior understanding will mean that you will have understood that this case compels me to act by in the very least soliciting that you grant me the freedom that corresponds to me.”[3] In a civil court, Natividad would have likely only petitioned to be sold to another master, as was dictated by the Spanish legal code of the time. However, due to her master’s position as a priest and member of the Church, she hoped that his immoral acts that violated the behavior expected of his position would cause the court to act in a more severe manner. At the beginning of her petition she states that “clearly my master forgot the obligations of his position, about Christianity and about authority when, on different occasions, he proposed his dishonest relations.”

Later, she once again appeals to the judge’s religious position, stating “I could very well lodge my appeal before the Señores of the Real Audiencia where the law of God has directed that slaves demand freedom whenever they seek the sanctuary and refuge that the law grants. But I wish that the secular courts should hear about the recklessness, indifferent, and tyrannies so foreign to leniency and self-restraint that an ecclesiastical priest professes. Thus, I renounce the indulgence of royal law and bring my case before the just commission of Your Most Illustrious Lord, who is very competent to reform the immoderate powers of a priest and decree what is in the interest of the pious cause of liberty that I claim.” In her language, Natividad clearly appealed to the religious nature of the court and the responsibility that they had for the behavior of a priest of their order.

Source: Wikimedia Commons.

Cases like Natividad’s reveal how enslaved and indigenous individuals viewed the Church not only as a site of religious devotion but more importantly as a powerful political institution where they could seek justice and social mobility. The fact that enslaved women, despite their legal and social subjugation, turned to the Church for recourse demonstrates the faith placed in its institutions, reinforcing its central role in colonial society as well as its popularity.

The wills of commoners, enslaved individuals, and indigenous people in colonial Spanish America reflect the profound influence of the Catholic Church. These documents not only served as legal instruments for dispensing wealth and property but also demonstrated investment in Catholic beliefs, rituals, and institutions. The consistent inclusion of religious donations, burial requests, and provisions for masses highlights how individuals—especially indigenous and African women—sought to secure their afterlife through the Church while reinforcing its central role in colonial society. Wills served as a final testament to religious devotion, illustrating how Catholicism shaped personal identity, social obligations, and cultural traditions across different racial and socioeconomic groups.

The will of Ana Copana, an indigenous woman born outside the city of La Plata who later became a property owner in the Andean highlands, exemplifies this deep religious commitment. Drafted in 1598, her will contains explicit instructions for her burial. She “order(s) that my [her] body be buried in the church of our Lord Saint Sebastian in the chapel of Our Lady of Copacabana and the customary alms be paid for the burial.”[4] Her will also contains explicit instructions for the number of masses to be said for her soul. She orders that “a requiem mass be sung over my body…eight masses be said for my soul in the parish of Saint Sebastian…another six masses be said for my soul and my executors pay the customary alms…another six masses for my soul, by selling a little bit of corn that I leave in a pirua.” Her burial choice at a chapel of significance that is quite far from her deathbed and emphasis on masses reflect how indigenous individuals actively engaged with Catholic practices, reinforcing the Church’s importance in both life and death.

Source: Wikimedia Commons

Similarly, the 1658 will of doña Ana de Barba y Talora, a divorced mestiza woman from Potosí, further illustrates the Church’s pervasive role in shaping individual legacies. In her will she orders “that my [her] body be buried in the principal church of this city” and “that one hundred low masses be said for my soul by the clergy that my executors wish and the customary alms be paid from my property.”[5] These requests indicate her desire for spiritual intercession. Beyond her own salvation, she left many religious paintings, statues, and cloths, such as “a statue of the Virgin of the Immaculate Conception” and “a canvas of Saint Gertrudis without frame” to her daughter and niece. The number of items left to her family emphasize the importance of Catholicism in her everyday life and her desire that her family maintain the faith. Ana de Barba y Talora also paid for the continuation of her blind daughter’s care and musical education, charging her daughter’s new guardians with “continuing to teach music as he has begun with my daughter so that she is sufficiently skilled to procure her a place in a convent. There she can serve the choir, and be kept for this ministry.” This request emphasizes how convent life was seen as both a religious vocation and a form of security for women. Both of these women’s wills reflect the popularity and influence of Catholicism and the Catholic Church among commoners and the indigenous people of colonial Spanish America.

The experiences of indigenous and African women in colonial Spanish America challenge the notion of passive subjugation, revealing instead their agency in navigating economic, legal, and religious structures to their advantage. Cities like Potosí provided avenues for wealth accumulation, property ownership, and legal literacy, while the Catholic Church functioned as both a spiritual and political institution that reinforced social mobility. Through wills, lawsuits, and participation in religious organizations such as cofradías, these women asserted control over their assets, secured their family’s future, and engaged in Catholic traditions that reinforced the Church’s authority in their communities. The Church’s accessibility, particularly through its tribunals, further solidified its popularity, as marginalized individuals viewed it as an avenue for justice and social mobility. The examination of the legal and economic strategies of indigenous and African women highlights how they actively shaped colonial society, proving that even within a complex legal system and enslavement, they found ways to exercise power.

Hope Payton is a junior at the University of Texas pursuing a BA in history with minors in Spanish and UTeach Liberal Arts. While completing her undergraduate degree, she has been involved in the creation of an online exhibit examining modernity in nineteenth century Latin America with the Benson Latin American Collection. She looks forward to student teaching social studies at the high school level her senior year

[1] Nora E. Jaffary and Jane E. Mangan, eds. Women in Colonial Latin America, 1526 to 1806: Texts and Contexts (Hackett Publishing Company, Inc., 2018), 34.

[2] Nora E. Jaffary and Jane E. Mangan, eds. Women in Colonial Latin America, 1526 to 1806: Texts and Contexts (Hackett Publishing Company, Inc., 2018), 41.

[3] Nora E. Jaffary and Jane E. Mangan, eds. Women in Colonial Latin America, 1526 to 1806: Texts and Contexts (Hackett Publishing Company, Inc., 2018), 208.

[4] Nora E. Jaffary and Jane E. Mangan, eds. Women in Colonial Latin America, 1526 to 1806: Texts and Contexts (Hackett Publishing Company, Inc., 2018), 36.

[5] Nora E. Jaffary and Jane E. Mangan, eds. Women in Colonial Latin America, 1526 to 1806: Texts and Contexts (Hackett Publishing Company, Inc., 2018), 45.

The views and opinions expressed in this article or video are those of the individual author(s) or presenter(s) and do not necessarily reflect the policy or views of the editors at Not Even Past, the UT Department of History, the University of Texas at Austin, or the UT System Board of Regents. Not Even Past is an online public history magazine rather than a peer-reviewed academic journal. While we make efforts to ensure that factual information in articles was obtained from reliable sources, Not Even Past is not responsible for any errors or omissions.