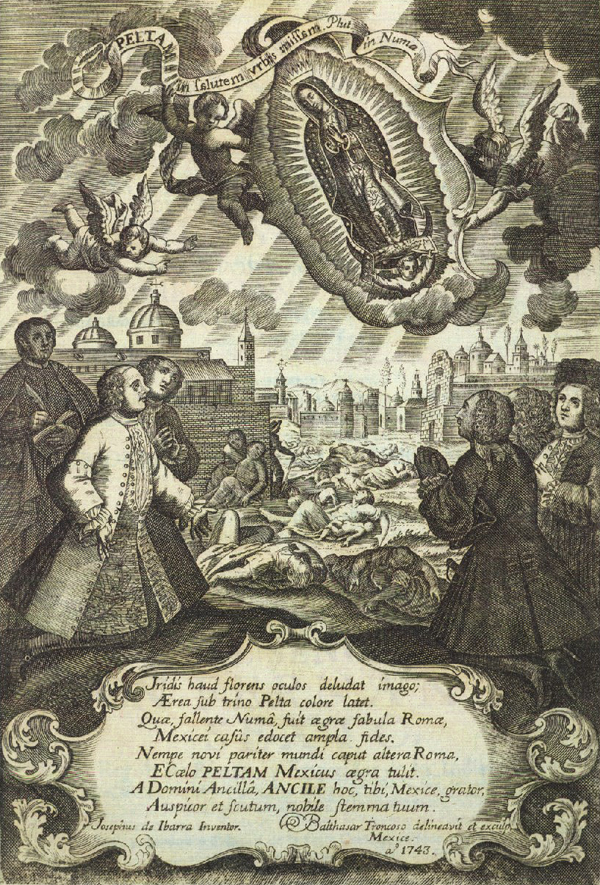

Chalice (Cáliz) Mexico City, 1575-1578 (via LACMA)

This series features five online museum exhibits created by undergraduate and graduate students at the University of Texas at Austin for a class titled “Colonial Latin America Through Objects.” The class assumes that Latin America was never a continent onto itself. The course also insists that objects document the nature of historical change in ways written archives alone cannot.

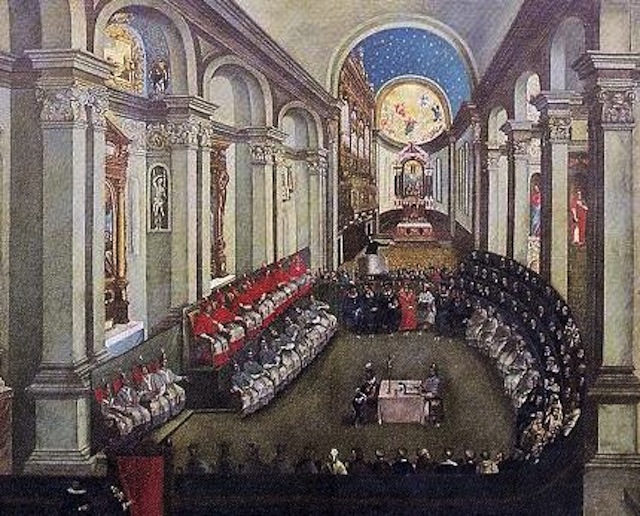

Lillian Michel’s exhibit focuses on colonial chalices, one of the most sacred objects of the Eucharist. Unlike many other colonial objects that incorporated indigenous techniques and materials, silversmiths charged with the production of chalices were strictly regulated. There was little room for the incorporation of indigenous materials, let alone indigenous religious sensibilities. Chalices therefore can better document the arrival of new European styles in art and architecture than changes in indigenous traditions.

More from the Colonial Latin America Through Objects series:

Of Merchants and Nature by Diana Heredia López

Nanban Art by John Monsour

Andean Tapestry by Irene Smith

Abisai Pérez Zamarripa reviews Indigenous Intellectuals: Knowledge, Power, and Colonial Culture in Mexico and the Andes

Brittany Erwin walks us through the National Museum of Anthropology in San Salvador

Jorge Cañizares-Esguerra reviews Jerónimo Antonio Gil and the Idea of the Spanish Enlightenment