By Deirdre Smith

A specter is haunting Europe (also the United States and, really, much of the globe)—the specter of a new Cold War. In recent years columnists have been invoking the memory of the global ideological conflict that governed much of the violence and geopolitics of the twentieth-century.[i] The reason for the comparisons is the eerie familiarity of the escalating conflict between Putin’s Russia and the United States and European Union. Tensions surrounding the annexation of Crimea, protests and military conflict in Ukraine, increases in sanctions against Russia, and divided support in the Syrian Civil War and refugee crisis have many people claiming redux.

On the cultural front, movies like Bridge of Spies and The Man From U.N.C.L.E. reflect a related desire to look back to the past for lessons about the present. As a student of the history of art in former Yugoslavia, I went to the archives held at the LBJ Presidential Library on the University of Texas at Austin campus following a similar impulse. I was looking for clues about the relationship between the United States and Yugoslavia during the critical years of the Lyndon Baines Johnson administration and how they reflected the larger divides between nations that are so frequently conjured today in the news.

When many Americans think about the history of United States relations with Yugoslavia, the Yugoslav Wars and the bombings in Belgrade in the 1990s likely come to mind. However, the two countries had long been ambivalent allies. As Yugoslavia’s President, Josip Broz Tito, had cut ties with the Soviet Union in 1948, he and his country were identified as useful in U.S. strategies to create divisions between communist nations.[ii] The United States provided military aid to Tito throughout the administrations of Truman and Eisenhower, hoping to keep the Yugoslav leader oriented toward positive relations with the West.

A Tomahawk cruise missile launches from the aft missile deck of the USS Gonzalez (DDG 66) headed for a target in the Federal Republic of Yugoslavia on March 31, 1999. Via Wikipedia.

The LBJ archives at UT hold numerous documents that give a first-hand impression of the nature and texture of relations between the United States and Yugoslavia as it proceeded through the 1960s. Ambassadors Eric Kocher and C. Burke Elbrick were stationed in Belgrade and both sent frequent telegrams to the Department of State that have been declassified only within the past fifteen years.

One of the most fascinating things I found in reading through these materials were traces of the growing divide between the United States and Yugoslavia following the assassination of John F. Kennedy, often in the smallest details. A cable from December 1963 summarizes a meeting held with President Tito in which Eric Kocher assured the Yugoslav leader that friendship would continue between the two countries after Kennedy’s death. Tito, who had met personally with Kennedy not long prior, apparently voiced some foreboding skepticism on the subject of Johnson. He also pressured the U.S. to be more attentive to the needs of South Americans, and inquired about the motivations and identity of the Kennedy assassin.[iii] The document suggests the intimacy between Tito and the United States at that point in time. Tito felt moved to express condolences and show interest in the case of Kennedy. He also took the same opportunity to discuss things that he wanted from the United States. Kocher mentions that all of these heady topics were covered in a span of only forty-five minutes.

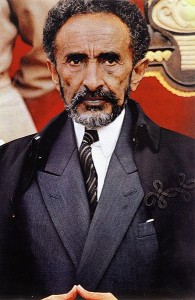

Josip Broz Tito greeting former American first lady Eleanor Roosevelt during her July 1953 visit to the Brijuni islands, PR Croatia, FPR Yugoslavia. Via Wikipedia.

In May 1964, President Johnson announced intentions to improve relations with Eastern European countries in terms of trade, travel and aid. Interest and activity around the United States embassies in Eastern European countries increased at this time. The Johnson administration attempted a détente with Moscow by becoming friendlier with Eastern Bloc countries at the same time that it amped up its commitments in Vietnam, creating a conflict that undermined the success of the former operation.[iv] Documents in the LBJ archives clearly convey a mounting tension in relations with Yugoslavia, which often manifested in events of daily life and personal interaction. Johnson’s more sweeping efforts at détente meant a diminished status for Yugoslavia as a key communist ally. In turn, Yugoslavia grew more open in its critiques of U.S. foreign policy.

On May 31, 1965, a telegrammed report from Eric Kocher alerted the State Department to signs of dissatisfaction with the United States appearing in the Yugoslav press, “Within the last year we have been under constant attack for our ‘misdeeds’ in the Congo, the UN, and especially in Vietnam and the Dominican Republic.”[v] Kocher’s scare quotes around the word misdeeds speak volumes about United States diplomatic attitudes. When reading in archives, being attentive to something as minute as a choice in punctuation and tone can offer tremendous insight. In this case, the special marking of misdeeds seems to reflect the same imperialistic attitude that the United States was being accused of by Yugoslav journalists. In June 1965, another cable summarized a meeting with Tito in which he made his loathing for the war in Vietnam clear. Tito told former ambassador George Kennan that U.S.-Yugoslavian relations would continue to suffer over their disagreements about the war. The document reads, “Tito said if U.S. took more relaxed posture toward world events things would work out to benefit of U.S. in long run.”[vi] If only it could be so simple.

These and other telegrams offer insight into the increasingly turbulent relationship between the United States and Yugoslavia in the 1960s under Johnson. Although files related to Yugoslavia make up a relatively small portion of what can be read at the LBJ Library, they reveal the constant and delicate activity of balancing contradictory initiatives and maintaining diplomatic relationships on the ground.

You may also like our monthly feature article on the War in Vietnam Revisited.

[i] See Dmitri Trenin, “Welcome to Cold War II: This is what it will look like,” Foreign Policy 3 March 2014.

[ii] For more on the relationship between the U.S. and Yugoslavia during these administrations see Lorraine M. Lees, Keeping Tito Afloat: The United States, Yugoslavia, and the Cold War (University Park, PA: Pennsylvania State University Press, 1997).

[iii] NATIONAL SECURITY FILE: Cable, Belgrade 3996, 12/6/63, Box 2, Country File, Yugoslavia, National Security File, LBJ Library.

[iv] See Jonathan Colman, The Foreign Policy of Lyndon B. Johnson: The United States and the World, 1963-1969 (Edinburgh: University of Edinburgh Press, 2010), 116-118.

[v] NATIONAL SECURITY FILE: Cable, Belgrade, 5/31/65 #12, Box 1, Country File, Yugoslavia, National Security File, LBJ Library.

[vi] NATIONAL SECURITY FILE: Cable, Belgrade, 6/3/65 #11, Box 1, Country File, Yugoslavia, National Security File, LBJ Library.