On March 23, 1961, recently-inaugurated President John F. Kennedy held a press conference at the State Department on Laos, a country little-known to most Americans at the time. Using a series of oversized maps, Kennedy detailed the advance of Communist Laotian and North Vietnamese forces in the country’s northeastern provinces. Rejecting an American military solution to the situation, Kennedy argued for a negotiated peace and a neutral Laos in hopes of containing the advance of communism in Southeast Asia. Before the Bay of Pigs disaster, before the Cuban missile crisis, and before serious escalation of American involvement in Vietnam, Laos presented the young president with his first major foreign policy dilemma. Kennedy’s wish for a peaceful, neutral Laos would be nominally achieved the following year, after months of negotiations. In accordance with the peace settlement, the United States withdrew its military advisors. The North Vietnamese did not.

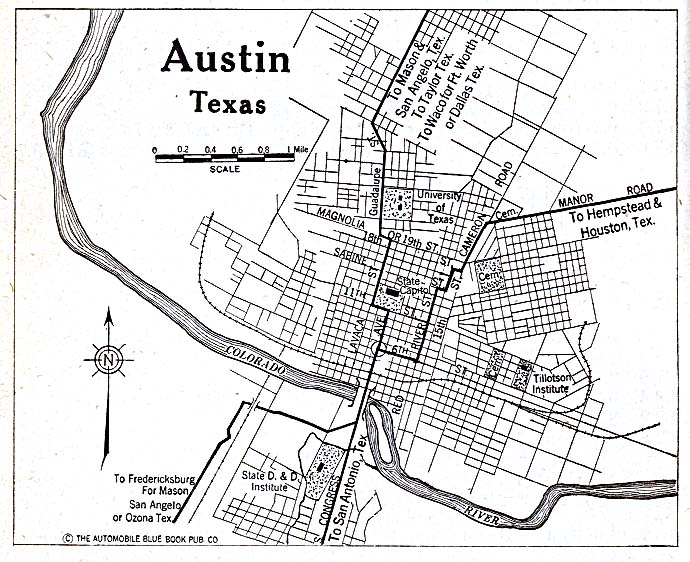

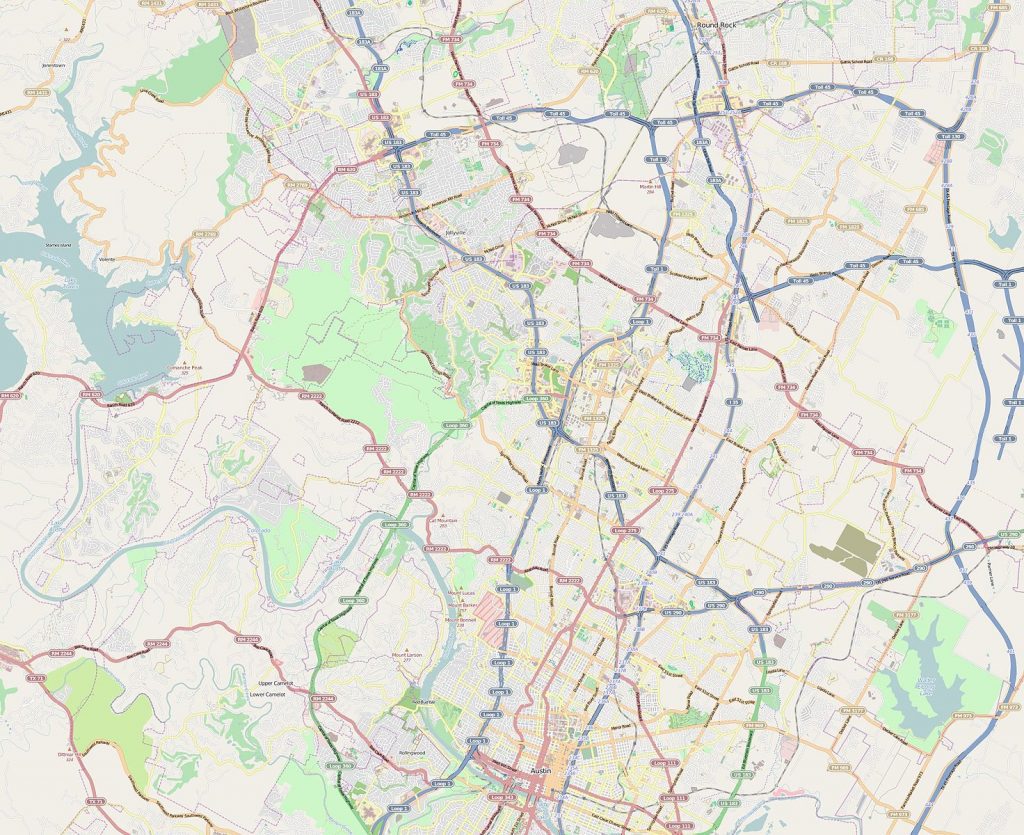

In Austin, Texas, a University of Texas graduate and staff member, Tom Ward, was one of the few Americans paying keen attention to the situation in Southeast Asia in the early 1960s. Born in 1931, Ward grew up in Austin, in the 1930s and 1940s a sleepy college and government town hardly recognizable as the rapidly developing, cosmopolitan capital that Texans are familiar with today. In a recent interview, Ward recalled his upbringing in the Old Enfield neighborhood, when the street’s paving ended at the Missouri-Pacific Railroad tracks, now Mo-Pac. At that time the University of Texas loomed even larger than it does today. As a boy, Ward attended a nursery school run by the university’s Department of Home Economics. He later attended many UT football games, paying a quarter to sit with his friends in a children’s section in the north endzone dubbed “the Knothole Gang.” In the pre-air-conditioned summers, Ward played in Pease Park and swam at Deep Eddy and Barton Springs. “I had a very pleasant experience growing up in Austin,” he remembers.

After graduating from Austin High School in 1949, Ward entered the University of Texas. He initially majored in business administration and pre-law, but finally decided to pursue his real interests: government and history. After graduating in 1954 with a degree in government and substantial coursework in history, Ward volunteered for the military. Having grown up during the Second World War, Ward said, “I felt that there was definitely an obligation to be in the service.” In 1955, Ward was sent to Fort Ord, California, for basic and advanced infantry training. He was initially designated to be sent as a replacement to Korea, but when it was discovered that he had a college degree he was reassigned to an anti-aircraft guided missile battalion at Fort Bliss, Texas. After serving out his time in the El Paso area, Ward returned to Austin, where in 1957 he began graduate work. He accepted an offer to work in the university admissions office the following year. It was at about this time that American involvement in Southeast Asia began to make headlines.

Ward had long held interests in government, history, and international relations, especially regarding Southeast Asia. He recalls with fondness that these interests were nurtured during his years at UT through courses in history, jurisprudence, and international relations with professors like William Livingston, James Roach, and Malcolm MacDonald in government; R. John Rath, Walter Prescott Webb, Otis Singletary, and Oliver Radkey in history; and George Hoffman in geography. In 1961, Ward had even taken a leave of absence from his position at UT to travel in Asia with a fraternity brother, a six-month trip that took them from Japan through East and Southeast Asia, India, the Middle East, and Europe, contracting hepatitis A along the way after drinking rice wine with a group of locals in Burma (now Myanmar). His adventures in 1961 were a harbinger of things to come. Ultimately, Tom Ward was destined for a life of service and overseas adventure far from the small, slow-paced Texas city where he had grown up.

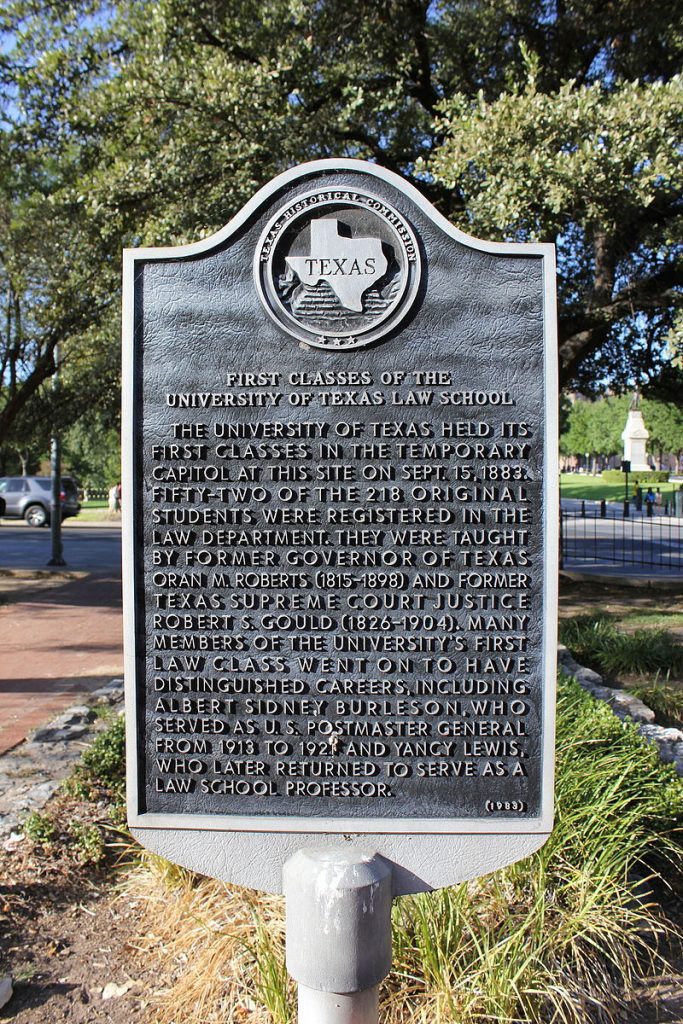

In 1962, after the short-lived farce of Laotian neutrality, President Kennedy responded to the continued Communist insurgency in the country by increasing America’s aid to the Royal Lao government through the Central Intelligence Agency and the United States Agency for International Development (USAID) channels. Kennedy hoped that a combination of assistance to ethnic minorities and economic aid to the country in general could stem the advance of the Communist Pathet Lao and their North Vietnamese allies without drawing US conventional military forces into the conflict. Given his experience and interests, it is little wonder that a professor at UT subsequently recommended Tom Ward to one of the State Department recruiters that fanned out over the country in search of potential aid workers for the American effort in Southeast Asia. With USAID in its infancy, Ward was interviewed by an official from the Bureau of Indian Affairs, the closest thing the U.S. government had at the time to a source of expertise in working with indigenous populations. Despite his awareness of the ongoing conflict in the country, Ward recalled, “I volunteered for Laos. … And the reason I wanted to go to Laos, [was] because of my experience at the university and I knew about Laos.” Before his new adventure commenced, however, one last memorable occasion on the Forty Acres came on March 9, 1962, when Ward was one of 1,200 students who packed into the Texas Union to hear an address on civil rights by Dr. Martin Luther King Jr.

Ward became one of six recruits selected to serve in Laos, with another twelve destined for Vietnam. Several months were spent at the University of California at Berkeley for training in local languages, Southeast Asian studies, and community development. Although they were civilian aid workers, Ward recalls, “community development training could also be considered counterinsurgency.” By April 1963, Tom Ward had become a foreign service officer and arrived in Laos, joining what became known as America’s “Secret War” in the small country.

Upon arrival in Laos, Ward found himself living with the Hmong ethnic minority group in a village called Sam Thong, working to coordinate the delivery of food, medical care, basic education, and other forms of humanitarian relief. Ward’s partner was the irascible Edgar “Pop” Buell, a former Indiana farmer and widower who had come to Laos in 1960 to work for International Voluntary Services, a private forerunner to the Peace Corps. It was in the mountainous northeastern provinces that the Pathet Lao guerillas were most active, and the indigenous Hmong formed the backbone of the CIA’s clandestine anti-Communist fighting force. In other words, Ward was now in a war zone.

Ward and Buell’s humanitarian work was necessitated by the Communist forces’ disruption of the traditional cycles of Hmong agriculture. By providing the Hmong with aid and basic services, the U.S. and Laotian governments hoped to maintain a counterinsurgency in the country and to strengthen the legitimacy of the Royal Lao government. “I lived in a grass hut with bamboo walls, a grass roof, dirt floor, no electricity, no plumbing, [and] a [55]-gallon drum out back for water. That’s where you bathed, and you lived like the local people did and ate their food,” recalls Ward. In addition to Ward and Buell, a CIA intelligence officer and a paramilitary officer were stationed nearby to coordinate training and military support for the Hmong.

Although Ward’s work in Laos was focused on humanitarian relief, the dangers of operating in a war zone were a fact of daily life. The only two roads leading into northern Laos were both blocked, so Ward and other American personnel were forced to move around the countryside on small short takeoff and landing (STOL) aircraft operated by Air America, a CIA-owned dummy corporation that played a vital role in the agency’s paramilitary efforts. Although “these were the best pilots in the world,” Ward says, travel in the war-torn country was filled with danger. Ward recounts many landings on airstrips that were shorter than 250 feet in length, or in some cases simply clearings on the side of a mountain. The planes negotiated low visibility and rugged terrain without instruments and avoided enemy anti-aircraft fire by flying as high as 10,000 feet, despite a lack of onboard oxygen. Once, Ward was supposed to go back to the capital city of Vientiane for a break, but a fellow aid worker had a date planned with a local woman and wanted Ward’s seat on the next plane. Ward gave up his spot on the flight. He learned later that the plane had crashed in the forest and had not been located for three days. Incredibly, the aid worker with whom he had swapped flights was still alive, albeit with severe burns that forced his evacuation from the country. On another occasion, mortar rounds began to land on a nearby position. With helicopter transportation seemingly unavailable at the time, Ward and his fellow workers prepared to walk out of the danger zone to safety. Finally, helicopters came and they were evacuated. Another memorable incident was the recovery of a US pilot who had been shot down and rescued by the Hmong.

Tom Ward served in Laos until January 1968, just before the Tet Offensive in neighboring Vietnam, at which time he was reassigned to the US mission in Thailand. As U.S. military involvement in Vietnam escalated, both aerial bombardment and ground fighting spilled over into Laos and Cambodia. Ultimately, all three countries would fall to Communist forces in 1975. Reflecting on the trajectory of events in Southeast Asia, Ward believes that the joint effort between the CIA and USAID was a successful counterinsurgency campaign that was derailed by U.S. military escalation in the region. “I think we . . . were there for the right reason and we did a good job,” says Ward, “and that forces beyond us took over and that’s why it ended up like it did.” Ward continues, “overemphasis on the military was counterproductive as far as I’m concerned.” Rather than a conventional military victory achieved through massive air power and ground combat, Ward believes that a counterinsurgency campaign could have achieved much different results in Southeast Asia.

In contrast to Laos, for a variety of reasons anti-Communist efforts in Thailand were ultimately successful. Like other Southeast Asian countries at the time, in the 1960s the Thai government sought American help to counteract a rural Communist insurgency. Ward worked for USAID in the Accelerated Rural Development program (ARD) between 1968 and 1975. This joint Thai-U.S. program sought to improve the local economies of the country’s troubled rural areas, thereby relieving their grievances and instilling confidence in the central government. Ward says the program was “like in the New Deal.” “I was in Chiang Rai for two years,” he continues, “and [I] worked with these programs in education, in health, and providing . . . improved rice seed to farmers, building roads so they could get their crops to market and this sort of thing.” Although the Communist insurgency continued in Thailand until 1989, Ward believes that “the standards of living were definitely raised in those areas. And if you go look at them today, it’s unbelievable the difference. You know, you have universities in a lot of these different places, a lot of these provinces where there was little economic development.”

After twelve years in Laos and Thailand, Ward returned to Washington, D.C., to work for the USAID Office of International Training. For the next five years, his career took him on short-term assignments to Nigeria, Tanzania, Egypt, Burma, Nepal, and Pakistan, helping to select candidates identified by their governments for graduate degrees and specialized technical training in the United States. From its founding to the time that he departed the program, Ward recalls, “we’d trained over 10,000 people” in fields such as agriculture, public health, finance, education, and a variety of governmental functions.

Ward was then assigned to Indonesia as a Development Training Officer working with the Indonesian government to select candidates for graduate training in American universities and short-term technical training with various U.S. government agencies. USAID’s training programs had a long-term impact on participating countries: at one point, six members of Indonesia’s governing cabinet had been trained in the United States. The goal, Ward says, was “to work yourself out of a job” as participating countries built indigenous governance capacity and technical expertise. Although the work was generally not as dangerous as his experiences in previous assignments, Ward still found himself in proximity to momentous events around the world. He was in Nigeria during a “transition from one dictator to another,” and he visited Kabul in 1978, on the eve of the Soviet-Afghan War (1979–1989).

In 1985, Tom Ward was called back to Washington, D.C., where he became a career counselor for foreign service officers. In 1991, after thirty years in service – twenty of them spent overseas – Ward retired from the State Department. Ward continued to work for a time as a government consultant in Kazakhstan, Uzbekistan, Turkmenistan, and Pakistan. Today he splits time between Washington, D.C., and Austin, punctuated with continued trips overseas.

Reflecting on his decades of experience as a foreign service officer, Ward was often astonished at the ignorance and apathy toward international events that he would encounter on visits home. While stationed in Laos, he says, “I’d come home on leave and they’d say, ‘Well, where [have] you been?’ ‘Well, I’ve been in Asia.’ ‘Oh, that’s interesting, tell me about it.’” Ward laughs. “And I’d get maybe two or three sentences, and then they’d change the subject: ‘Oh by the way, did you see ‘I Love Lucy’ last night?’” Ignorance of foreign cultures could also be a problem in government agencies and the military. Although he believes that in Southeast Asia, “a lot of these people were very dedicated officers and men… they were not taught to learn about the culture, speak the language, learn how the people felt about things, and how to work with them from their point of view, if at all possible.” This lack of understanding failed both the United States and the people of Laos and Vietnam. Ward believes that the situation has improved over time, but familiarity with foreign cultures and political systems remains a key variable in the success or failure of U.S. efforts overseas.

After a career spent in public service, Ward has not been content to simply focus on personal pursuits in retirement. Over time he has become increasingly active in supporting the institution that molded his interests and opened the door to his career: The University of Texas at Austin. Ward has found ways to volunteer his time and leadership over the years, joining the College of Liberal Arts Advisory Council shortly after his retirement and the Department of History Visiting Committee a few years later. He is currently in the process of establishing a chair in international relations in the College of Liberal Arts.

Ward’s career has informed his involvement with UT. In his experience, the best way to improve lives is “through education, in this country or overseas.” He continues, “What we were doing overseas [was] giving them development opportunities they didn’t have.” As a foreign service officer Tom Ward worked to improve the economies and governments of other countries. Now he sees similar opportunities closer to home, through UT’s ability to increase American understanding of the international context and in the university’s potential to aid underserved and non-traditional student populations.

Dr. Nicholas Roland is a historian at the Naval History and Heritage Command, Washington, D.C. He earned his PhD from The University of Texas at Austin in 2017. A revised version of his dissertation, “Violence in the Hill Country: The Texas Frontier in the Civil War Era,” is forthcoming from UT Press.

Sources:

Tom Ward oral history, April 19, 2018

//www.jfklibrary.org/Asset-Viewer/Archives/JFKWHA-020.aspx

//history.state.gov/milestones/1961-1968/laos-crisis

You May Also Like:

What Not to Wear at a Texas Barbecue

In the Trenches

U.S. Survey Course: Vietnam War

The views and opinions expressed in this article or video are those of the individual author(s) or presenter(s) and do not necessarily reflect the policy or views of the editors at Not Even Past, the UT Department of History, the University of Texas at Austin, or the UT System Board of Regents. Not Even Past is an online public history magazine rather than a peer-reviewed academic journal. While we make efforts to ensure that factual information in articles was obtained from reliable sources, Not Even Past is not responsible for any errors or omissions.