By Edward Shore

Civil war and unrest have triggered a global humanitarian disaster without parallel in recent history. In June 2015, the United Nations High Commission for Refugees reported that the number of refugees and internally displaced people had reached its highest point since the Second World War. Violence in countries like Iraq, Syria, Afghanistan, Somalia, and Sudan has forced more than 60 million men, women, and children from their homes. One in every 122 people worldwide is a refugee or an internally displaced person (IDP). More than 9.5 million Syrians, roughly 43% of the Syrian population, have been displaced since 2012. The majority of asylum seekers have re-settled in Turkey, Jordan, and Lebanon. Yet a rising tide of virulent xenophobia has inflamed much of Europe and the United States.

Texas has opposed President Obama’s plan to grant asylum to 10,000 Syrian refugees in 2016. Nearly half of all Texans support banning non-U.S. Muslims from entering the country and more than half support the immediate deportation of all undocumented immigrants now living in the U.S. Last December, Texas Attorney General Ken Paxton filed suit against the Obama administration to block the relocation of refugees from Syria to Texas. Governor Greg Abbott has vowed to use next year’s legislative session to punish “sanctuary cities,” a loose term describing municipalities that refuse to cooperate with federal immigration authorities. One Austin-based non-profit organization is leading the charge to defend Texas’ refugees.

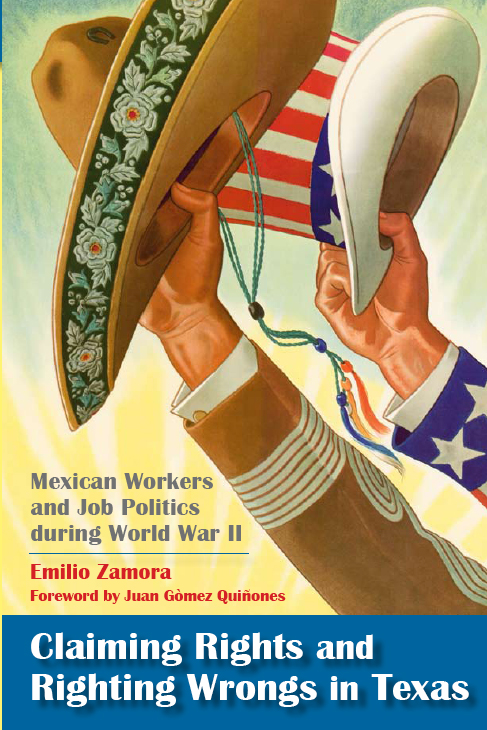

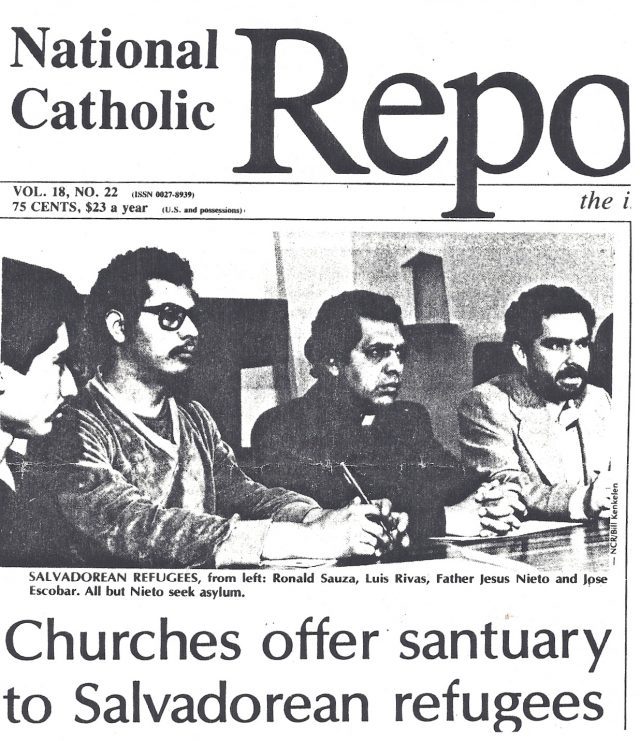

Casa Marianella is a transitional shelter for refugees and asylum seekers in East Austin. It emerged during the Sanctuary Movement, a religious and political campaign that provided safe-haven to refugees fleeing civil wars in Central America during the early 1980s. At its height, the Sanctuary Movement comprised a network of 500 religious congregations that provided shelter and legal counsel to Salvadoran and Guatemalan refugees. Advocates acted in open defiance of U.S. immigration law. Over half a million Guatemalans and Salvadorans arrived to the United States during the 1980s. The vast majority were civilians fleeing atrocities perpetrated by anti-communist paramilitaries. Yet the Reagan administration, which supported right wing military juntas in their crusade against leftist insurgencies in El Salvador and Guatemala, accepted less than three percent of all asylum applications from those countries. The U.S. government argued that Guatemalans and Salvadorans were “economic migrants” fleeing poverty, not governmental repression. In 1983, the United States granted political asylum to one Guatemalan.

Activists Ed Wendler, Mercedes Peña, and Jennifer Long were members of the Austin Interfaith Task Force for Central America, an ecumenical peace coalition that opposed U.S. military aid to Central America. In the fall of 1985, they lobbied Mayor Frank Cooksey to declare Austin a “sanctuary city.” The city council, under intense pressure from anti-immigration groups, rejected the proposal. Unfazed, the Austin Interfaith Task Force for Central America established a residential space to serve the needs of refugees in East Austin’s Govalle neighborhood. Casa Marianella opened its doors to dozens of Salvadoran and Guatemalan asylum seekers on January 6, 1986. Casa’s namesake honors the memory of Marianella García Villas, a Salvadoran human rights lawyer who was assassinated by paramilitaries in March 1983. She was a close associate of Archbishop Oscar Romero, who was assassinated in San Salvador by state security forces while celebrating mass on March 24, 1980.

Today, Casa Marianella provides shelter and social services to asylum seekers from 28 different countries, including Colombia, Nepal, India, Angola, and Nigeria. The shifting demographics correspond to recent changes in U.S. immigration policy. “It’s much harder to cross the U.S. border from Mexico today than it was thirty years ago,” explained Jennifer Long, current executive director of Casa Marianella.

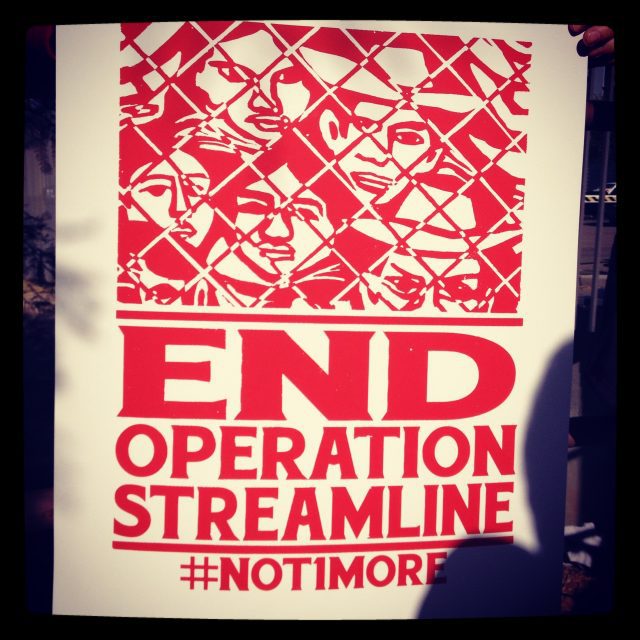

In 2005, the Department of Homeland Security and the Department of Justice launched Operation Streamline, a “zero-tolerance” approach to unauthorized border crossing. Those caught at the U.S. border in Arizona, New Mexico, and Texas may be subject to criminal prosecution for misdemeanor illegal entry, an offense that carries a six-month maximum sentence. Any migrant who has been deported in the past and attempts to re-enter without authorization can be charged with felony re-entry, an offense that carries a two year maximum sentence. Ninety-nine percent of detainees prosecuted under Operation Streamline plead guilty. Detainees from Mexico and Central America are often placed in removal proceedings.

By contrast, refugees from the Horn of Africa are jailed at ICE detention centers pending the outcome of their asylum cases. This is because the U.S. government cannot deport people to states without recognizable governments. Detainees seeking asylum that ICE determines not to be flight risks or threats to national security can secure release after posting bond. This is how most refugees arrive at Casa Marianella. In 2015, the majority of Casa’s residents came from Eritrea, Ethiopia, and Somalia. Several must still wear ankle monitors, including a father and his young daughter, while they await the court’s decision on their asylum requests.

As one of the last remaining shelters for asylum seekers in the United States, Casa Marianella labors to meet the needs of the country’s swelling refugee population. Last Friday, a deluge of collect calls poured into Casa Marianella from ICE detention facilities in Port Isabel, Pearsall, Hutto, Taylor, and Karnes, Texas. Others called from Krome, Florida, where a federal judge boasts a 95% denial rate for asylum seekers. Casa Marianella reserves space for 38 residents but currently shelters 51. Although overcrowded, the organization still manages to assist the majority of its residents and the refugee community at large to secure legal counsel, work, medical care, English classes, and a place to call home. Of the 188 refugees who entered Casa’s adult shelter last year, 92% successfully exited. Casa’s triumph is a testament to the compassion, dedication, and courage of its staff, volunteers, and residents.

Mattias is an asylum seeker from Eritrea. He visited Casa’s office last Friday when I interviewed Jennifer Long. Mattias arrived at Casa last year and has since found a stable job and lives with his family in an apartment in East Austin. “What’s the secret for your success, Mattias?” I asked. “Oh, just walking here,” he replied. “That’s it. Nothing else.”

Now, more than ever, Casa Marianella needs volunteers. Students and faculty with language skills can get involved by interpreting for pro bono attorneys who are working on residents’ asylum cases. For instance, I recently interpreted for an Angolan refugee fleeing sectional violence in Luanda. I also officiated a wedding in Portuguese for an Angolan couple at Casa. Posada Esperanza, Casa’s women and children’s shelter, needs volunteers to assist students with their homework. Others are needed to help prepare and clean up after meals. Finally, join Casa residents and staff from 6-8 pm every last Sunday of the month for “Convivio,” a celebration of community with live music, dancing, and ethnic cuisine.

To volunteer, please email volunteer@casamarianella.org.

Disclaimer: I used pseudonyms to protect the anonymity of Casa’s residents.

The views and opinions expressed in this article or video are those of the individual author(s) or presenter(s) and do not necessarily reflect the policy or views of the editors at Not Even Past, the UT Department of History, the University of Texas at Austin, or the UT System Board of Regents. Not Even Past is an online public history magazine rather than a peer-reviewed academic journal. While we make efforts to ensure that factual information in articles was obtained from reliable sources, Not Even Past is not responsible for any errors or omissions.

The horrific violence left as many as 15,000 dead. Trujillo apologists managed to justify the action nationally, but the massacre created an international public relations nightmare for the regime. Newspapers cited Trujillo’s ruthlessness and compared him to

The horrific violence left as many as 15,000 dead. Trujillo apologists managed to justify the action nationally, but the massacre created an international public relations nightmare for the regime. Newspapers cited Trujillo’s ruthlessness and compared him to

the extent to which the Cuban missile crisis increased U.S.-Soviet cooperation and discr

the extent to which the Cuban missile crisis increased U.S.-Soviet cooperation and discr