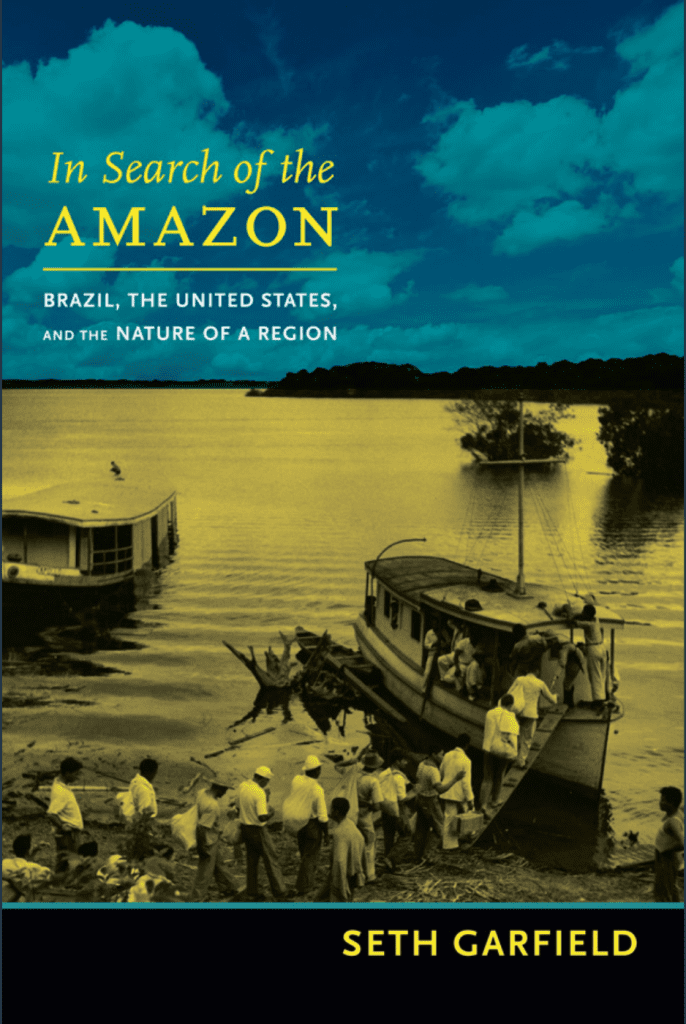

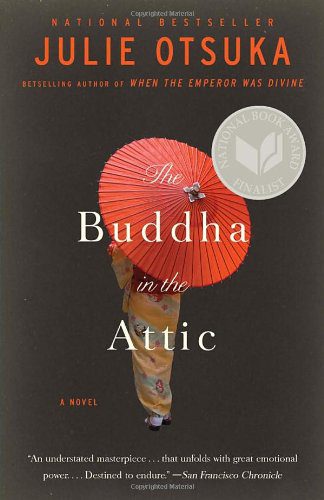

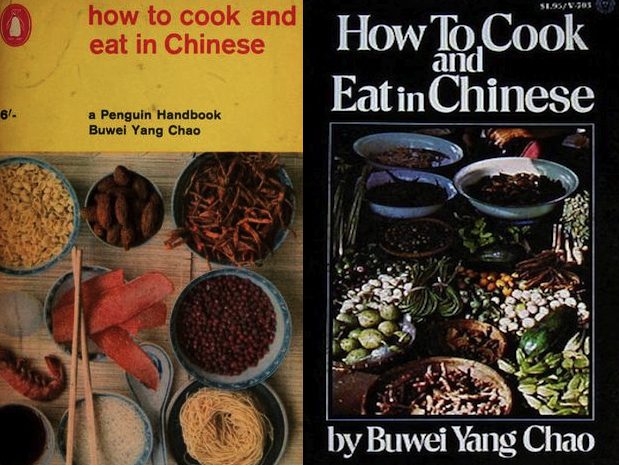

How to Cook and Eat in Chinese was the earliest popular, English-language guide to Chinese cooking. First published in 1945 and reprinted several times, it remains in wide use today. The author, Dr. Buwei Yang Chao, wrote the cookbook at the urging of fellow faculty wives in New Haven, in particular Agnes Hocking, wife if the idealist philosopher William Hocking. Trained as a physician, Dr. Chao reassured American housewives that she could teach them the complex and exotic art of Chinese cooking because she had learned as an adult herself while a student in Japan.

In addition to providing straightforward and simple directions together with suggestions for obtaining ingredients and alternatives, How to Cook and Eat in Chinese presents its guidance with wit and whimsy provided by Dr. Chao’s husband and translator, the famous linguist Dr. Yuen Ren Chao, who created terms now in common usage such as “stir fry” and “potsticker.” Footnotes add humorous asides that explain family disputes over translations and descriptions for Chinese cultural practices. For example, in the introduction, the language specialist Yuen Ren Chao cannot resist adding a footnote to the otherwise commonplace, “Really, you should not have put yourself to so much trouble!” to explain that this translation is inaccurate because Chinese lacks the “subjunctive perfect.”

Dr. Buwei Yang Chao’s cookbook was so successful that the well-known author, Pearl Buck, who wrote one of its prefaces from the point of view of an American housewife, urged Chao to pen the story of her life. Autobiography of a Chinese Woman appeared in 1947. With great charm, Chao made a persuasive case for the educated, cosmopolitan Chinese family to be accepted as American. The success of Dr. Buwei Chao’s publications bridging Chinese and American peoples underscores the intrinsic relationship between popularizing ethnic food and the assimilation of ethnic and racial minority groups. As Donna Gabaccia wrote in We Are What We Eat: Ethnic Food and the Making of Americans, after World War II, ethnic foods such as Chinese and Italian, would win broader appreciation as part of a more general expansion of the boundaries of mainstream American culture and society.

Dr. Buwei Yang Chao’s cookbook was so successful that the well-known author, Pearl Buck, who wrote one of its prefaces from the point of view of an American housewife, urged Chao to pen the story of her life. Autobiography of a Chinese Woman appeared in 1947. With great charm, Chao made a persuasive case for the educated, cosmopolitan Chinese family to be accepted as American. The success of Dr. Buwei Chao’s publications bridging Chinese and American peoples underscores the intrinsic relationship between popularizing ethnic food and the assimilation of ethnic and racial minority groups. As Donna Gabaccia wrote in We Are What We Eat: Ethnic Food and the Making of Americans, after World War II, ethnic foods such as Chinese and Italian, would win broader appreciation as part of a more general expansion of the boundaries of mainstream American culture and society.

User-friendly ethnic cookbooks such as How to Cook and Eat in Chinese brought once alien cultures and foodways directly into the kitchens and homes of Euro Americans. According to Fashionable Food: Seven Decades of Food Fads by Sylvia Lovegren, family meal preparation was not only a commonplace form of domestic labor, but one that provides keen insights into broader historical trends. During the Cold War and the Civil Rights era, these shifts emerged in part through the growing popularity of ethnic foods and cookbooks. Dr. Buwei Chao was an early forerunner of the trends that by the late 1960s and early 1970s mobilized leading figures in the food publishing business, such as Judith Jones, Julia Childs’ editor at Knopfand Craig Claiborne, the New York Times food critic, to recruit cooks with ethnic food expertise, personality, and writing ability to introduce general audiences to their cultures.

Jones’ discoveries, sometimes promoted in conjunction with Claiborne, included southern chef, Edna Lewis of Café Nicholson who authored The Edna Lewis Cookbook (1972) and The Taste of Country Cooking (1976); scholar Claudia Roden and A Book of Middle Eastern Food (1968); the late Marcella Hazan and The Classic Italian Cookbook (1973); and restaurant owner Irene Kuo with The Key to Chinese Cooking (1977). Claiborne’s entry into the Chinese cookbook field was The Chinese Cookbook (1972) which he co-authored with Virginia Lee. Both Hazan and Lee attracted Jones and Claiborne’s attention when they began offering cooking lessons out of their homes.

Jones’ discoveries, sometimes promoted in conjunction with Claiborne, included southern chef, Edna Lewis of Café Nicholson who authored The Edna Lewis Cookbook (1972) and The Taste of Country Cooking (1976); scholar Claudia Roden and A Book of Middle Eastern Food (1968); the late Marcella Hazan and The Classic Italian Cookbook (1973); and restaurant owner Irene Kuo with The Key to Chinese Cooking (1977). Claiborne’s entry into the Chinese cookbook field was The Chinese Cookbook (1972) which he co-authored with Virginia Lee. Both Hazan and Lee attracted Jones and Claiborne’s attention when they began offering cooking lessons out of their homes.

America’s immigrant population and the broad acceptance of ethnic cultures and communities have boomed along with the popularity of ethnic restaurants, cookbooks, cooking shows, and personalities. For an understanding of the early roots of this business and cultural phenomenon, revisit Buwei Yang Chao’s How to Cook and Eat in Chinese.

You may also like:

Judith Jones, The Tenth Muse: My Life in Food (2007)

Craig Claiborne, A Feast Made for Laughter (1982)

Photo Credits:

Book jackets of How to Cook and Eat in Chinese (Image courtesy of Asian American Writers’ Workshop)

Food market in New York City’s Chinatown (Image courtesy of Wikimedia Commons/User Momos)