By David Crew

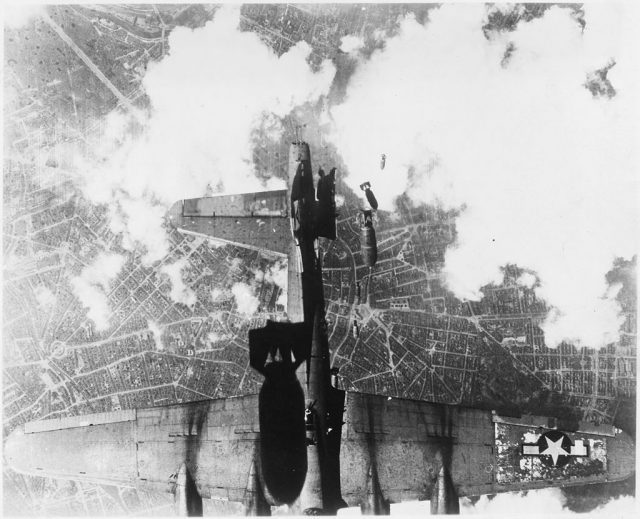

At the beginning of September 2017, construction workers in the major west German city of Frankfurt am Main uncovered a British “blockbuster” bomb dropped during World War Two. Nearly 60,000 residents were evacuated so that experts could defuse this huge bomb designed to destroy an entire street of houses. Unexploded bombs from World War Two are still being discovered in other German cities. During the war, the British and the Americans dropped some 2.7 million tons of bombs on Germany. All the major German cities were reduced to ruins and between 305,000 and 410,000 Germans, most of them women, children, and old people were killed, sometimes in quite hideous ways, by Allied bombs. By the 1990s, however, many Germans would insist that this traumatic experience had been overshadowed by Germany’s confrontation with the Holocaust. The experience and suffering of German civilians during the Allied air war appeared to be “off-limits,” the subject only of private conversations around the family dinner table but never a major focus of public memory. Germans who had lived through the bombing were, it appeared, victims twice over—victimized by the bombing itself and then by the silence to which they were allegedly condemned after 1945.

and old people were killed, sometimes in quite hideous ways, by Allied bombs. By the 1990s, however, many Germans would insist that this traumatic experience had been overshadowed by Germany’s confrontation with the Holocaust. The experience and suffering of German civilians during the Allied air war appeared to be “off-limits,” the subject only of private conversations around the family dinner table but never a major focus of public memory. Germans who had lived through the bombing were, it appeared, victims twice over—victimized by the bombing itself and then by the silence to which they were allegedly condemned after 1945.

Yet, far from being marginalized in postwar historical consciousness, the bombing war was a central strand of German popular memory and identity from 1945 to the present. In the late 1940s and early 1950s, local narratives of the bombing war established themselves as important “vectors of memory.” Not produced by professional historians and usually lacking any scholarly pretensions, these local publications are examples of the kind of “public history” which has been so influential in constructing and transmitting popular understandings of the past to successive generations of Germans since 1945. Along with the flight and mass expulsions of ethnic Germans from the East and the mass rapes of German women by Soviet soldiers, the bombing war allowed Germans to see themselves as victims at a time when the Allied liberation of the concentration camps and the Nuremberg trials presented Germans to the world as perpetrators or at least as accomplices. The bombing war continued to serve this function even as Germans became more and more willing directly to confront the genocide of European Jews –which by the 1960s was beginning to be referred to as the Holocaust.

The power of the local master narrative established in the 1950s depended upon its ability to compress the local memory of the war and the Nazi past into the experience of the bombing. This version of local history depicted the inhabitants of individual towns and cities as innocent, unsuspecting victims of both Allied bombs and of the Nazi regime which had deceived and misled them. But by the late 1990s, this narrative had become intensely problematic. New scholarship, the activities of local History Workshops, public controversies about the traveling exhibition “Crimes of the Wehrmacht” (1995-1999) and about Daniel Jonah Goldhagen’s book, Hitler’s Willing Executioners: Ordinary Germans and the Holocaust (1996) all focused public attention on the participation of ordinary Germans in the crimes of the Nazi regime. At the end of the twentieth century, it seemed no longer possible to decontaminate local history.

Photographic images played essential roles in local publications about the bombing war. Photographs were used not simply to illustrate the written text but also to show aspects of the bombing war that the authors believed could not be communicated adequately in words. Yet the power of images was limited by the conditions under which they had been produced during and immediately after the war. Photographers had simply not been able to capture pictures of some of the most horrific experiences of the bombing. The images that were used might also generate contradictions that could not be resolved visually. Photographs of dead German bodies might conjure up the other images of dead and dying Jews and other concentration camp victims which the occupying Allies had used as evidence of German crimes in 1945. The early local publications established a fairly limited visual canon which relied primarily upon pictures of ruins and (less frequently) dead German bodies to construct a visual argument that presented Germans as victims. But as the repertoire of images expanded in the 1960s to include pictures of Allied air crews, of Jews or other victims of Germans, as well as photographs of the European cities destroyed by German bombing, these other images made it more difficult to maintain an exclusive focus on German suffering.

Pictures of ruins have remained the most common motif in publications about the bombing right up to the present but the genre of ruin pictures has changed significantly since 1945. Ruin pictures now routinely include photographs of cities bombed by the Germans–Guernica, Warsaw, Rotterdam, London, Stalingrad. Pictures of forced foreign laborers, Russian POWs and even Jews in the ruins draw attention to Nazi racism and genocide. The important question is, however, not whether but how these pictures of Germany’s victims have entered the visual world of the bombing war. Are they presented in ways that require readers to look at the suffering caused by Germany while still allowing them to empathize with the German victims of the bombing? Or do they seriously disrupt the ability of photographs of Germans in the ruins to elicit the sympathy of contemporary readers/viewers? Or do pictures of Germany’s victims, when they are set side-by-side with images of Germans as victims, show readers that World War Two turned ordinary people on all sides into victims and created a European-wide community of suffering?

The most recent visual and textual representations exhibit no clear agreement on the “right” narratives and the “right” images that should be used to depict the bombing of German cities. A range of different voices and pictures now compete for the attention of German audiences. This “pluralization” of bombing narratives and images both reflects and enables the competing, sometimes contradictory ways that Germans imagine the air war and its relationship to the Holocaust.

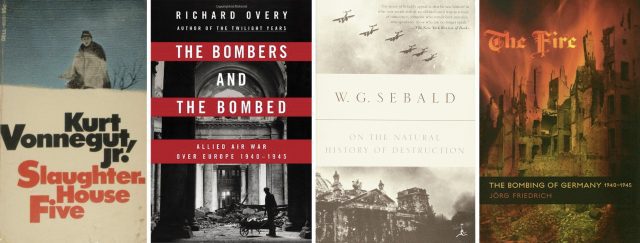

Kurt Vonnegut, Slaughter-house Five (1969).

The classic novel by one of America’s most important writers. Vonnegut was a POW in Dresden when the city was devastated by Allied firebombing on February 13-14, 1945

Richard Overy, The Bombers and the Bombed. Allied Air War Over Europe, 1940-1945 ( 2015)

An unusual approach by the eminent British historian of World War Two that provides a comprehensive discussion of the Allied bombing of not just Germany but of many other European countries

W.G. Sebald, On the Natural History of Destruction(2003).

In this provocative short collection of essays, translated from the German original, the author and literary critic, W.G. Sebald faulted German writers for not having made the air war a more central and significant focus of post-war literature.

Jörg Friedrich, The Fire:The Bombing of Germany, 1940-1945 (2006).

The English translation of Friedrich’s massive, tendentious and hotly contested critique of the Allied air war which quickly became a bestseller in Germany.

Dresden (Dir: Roland Suso Richter, 2006). The first fiction film about the fire-bombing of Dresden. It drew an audience of 13 million viewers on the first evening it was broadcast on German television in March 2006.