Colonial Latin America through Objects examines the material cultures of colonialism in Latin America from the fifteenth to the nineteenth centuries. It is a new version of a course first created and taught with tremendous success by my distinguished colleague Jorge Cañizares-Esguerra. It was also one of the first courses I taught after joining UT.

My aim was to create a student-centered research course, revolving around students’ own engagement with a range of colonial objects that are available in the physical and digital collections at The University of Texas at Austin. The course invites students to explore the relationships people established with material objects and how they used them. In the process, students learn how life in Latin America changed following the Spanish colonial project. We focus on objects that reveal the dynamics of cultural interaction between Native Americans, Africans, and Europeans and their changes over time. We consider the things people wrote, wore, ate, where people lived, and what they used to exchange with one another as a way to understand their standing in society and the larger power and economic structures that shaped their experience and sensibilities under a colonial order. In this way, it takes material culture as a window to understand colonialism.

The class is constructed around four cycles of independent investigation, which students can do individually or in groups of up to four people. The cycles are organized around a specific category of objects:

- Scriptures and modes of writing

- Landscapes and maps

- Clothing and items around the body

- The economic value of things.

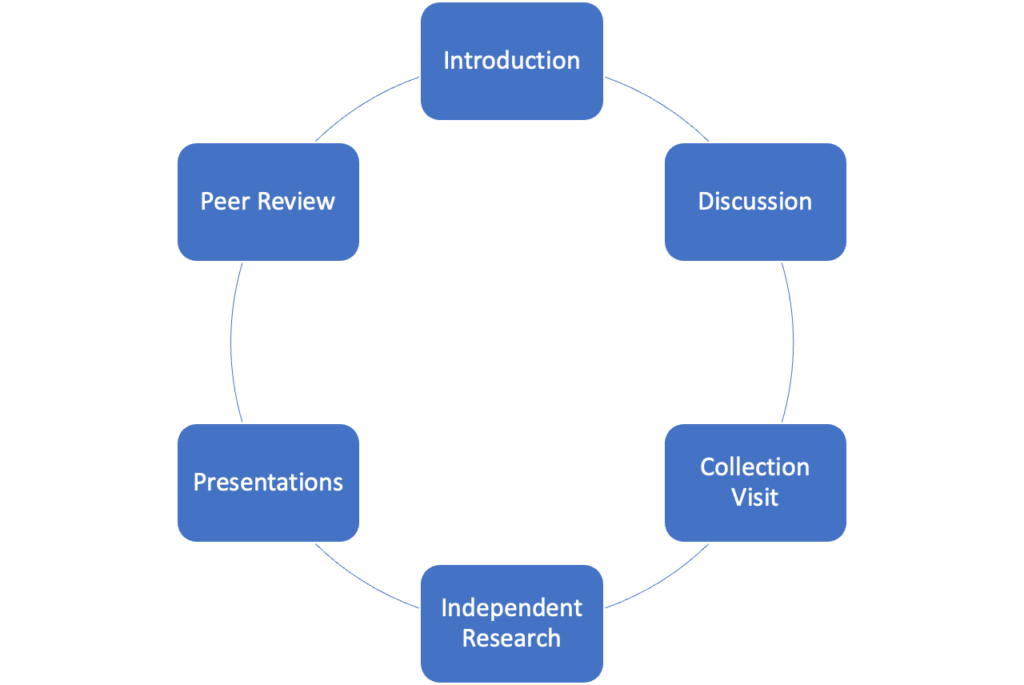

These cycles, in turn, break into a set of repeating elements. Each of these cycles follows a common structure, with sessions devoted to:

- A lecture introducing the main subject of the cycle,

- The discussion of readings,

- A collection visit, in which students identify a primary object they would like to work with,

- Independent research on each group’s object, along with meetings with the instructor,

- Presentations to the class of preliminary findings,

- Peer review of the drafts of the papers.

The expectation is that the lecture and reading sessions prompt student questions and open avenues for analysis as students interrogate the objects they selected during the collection visit. My goal was to foster a collaborative environment in which each group’s research is enhanced through socialization and peer review.

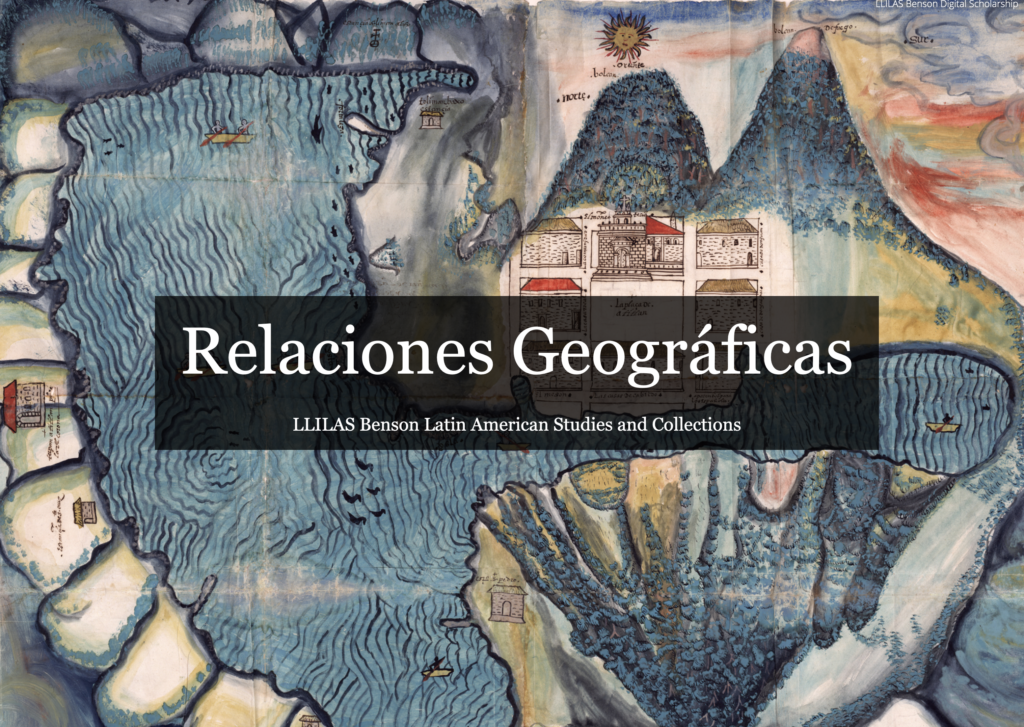

UT Austin, with its rich collections of colonial Latin American history and fabulous team of curators, is the perfect setting for this kind of class. In the Fall of 2022, we visited the Benson Latin American Collection twice, the first time analyzing printed and manuscript written documents and the second time exploring Indigenous maps of the Relaciones Geográficas de Indias. We also visited the Blanton Museum, which was then hosting its Painted Cloth exhibit.

Finally, we ventured through some of the digital collections, like The New Spain: An Exhibition, Primeros Libros de las Américas, or Benson’s digitized imprints and images. Students had a chance to step out of the classroom and engage with some of UT’s finest curators and archivists, like Adrian Johnson and Ryan Lynch from the Benson, Rosario Granados from the Blanton Museum, and Albert Palacios from the Benson and the School of Information Sciences. Students got to think through the meaning of objects and collections with their custodians.

![Nuestra Señora de Belén con un donante [Our Lady of Bethlehem with a Donor].](https://notevenpast.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/09/Nuestra-Senora-de-Belen-con-un-donante_with-frame-684x1024.jpg)

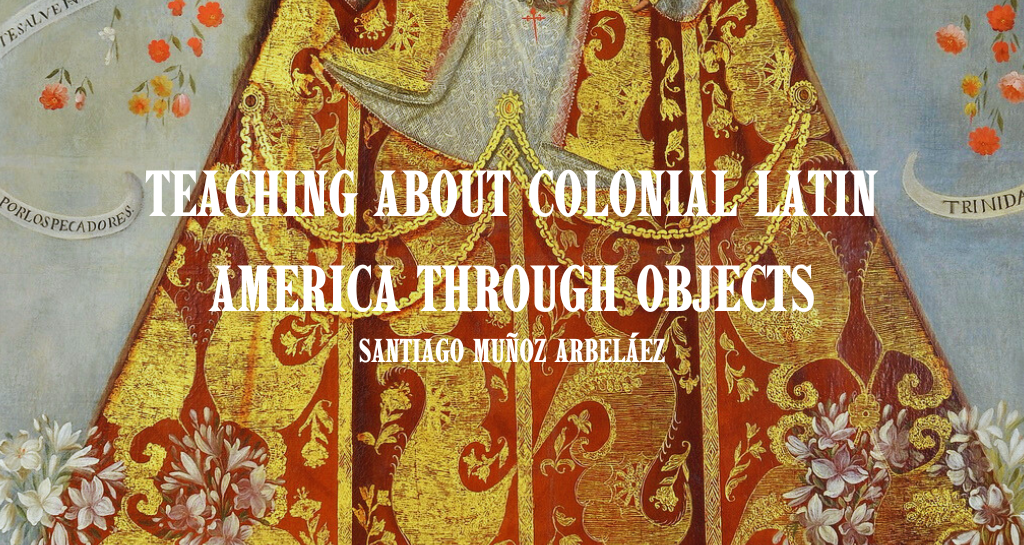

Students wrote essays on topics like the role of Malintzin—a Nahuatl woman who served as interpreter of Hernán Cortés—in the Lienzo de Tlaxcala, the silences about the narration of the conquest in an early Hernán Cortés letter, the notion of Indigenous bodies in an early modern Spanish medical treatise, the depiction of colonial spaces in Indigenous maps, the presence of Indigenous donors in Catholic art, or the depiction of race and guild in Peruvian casta paintings. In one of the four modules, students structured their research in a creative format, other than a traditional essay. Students created websites, videos, and even two radio episodes that aired in Guadalajara, Mexico.

I really enjoyed the course and the students seemed to get a lot out of it. In their evaluations, students remarked they found it challenging but rewarding to consider how people engaged with objects in a very different period, formulating questions and designing research strategies. They enjoyed being pushed out of the classroom and immersed in a collaborative environment where they learned from each other and developed their own projects.

Santiago Muñoz Arbeláez is an Assistant Professor of History at the University of Texas at Austin. His research and teaching focus on the interactions between Indigenous peoples and European empires in the early modern Atlantic world, combining material culture, agrarian history, and the history of books and maps. His first book, Costumbres en disputa. Los muiscas y el imperio español en Ubaque, siglo XVI (Bogotá: Ediciones Uniandes, 2015) reframed the history of the encomienda—one of the most contentious institutions of the Spanish empire—through an ethnographic look at everyday interactions between Muiscas and Europeans. His current book project, tentatively titled Empire’s Fabric: The Making and Unmaking of New Granada, examines the making of a centralized political entity (a “kingdom”) among the ethnically and geographically diverse landscapes of the northern Andes.

Banner image comes from Anonymous, “Nuestra Señora de Belén con un donante [Our Lady of Bethlehem with a Donor],” Blanton Museum of Art Collections, accessed September 12, 2023, http://utw10658.utweb.utexas.edu/items/show/3243.

_________________________________________________________________________________________

The views and opinions expressed in this article or video are those of the individual author(s) or presenter(s) and do not necessarily reflect the policy or views of the editors at Not Even Past, the UT Department of History, the University of Texas at Austin, or the UT System Board of Regents. Not Even Past is an online public history magazine rather than a peer-reviewed academic journal. While we make efforts to ensure that factual information in articles was obtained from reliable sources, Not Even Past is not responsible for any errors or omissions.