This book has been an intellectual adventure to read, all 600-plus pages of it. The Scientific Revolution, Ralph Bauer argues, carries a connotation of “the discovery of new worlds” in nature. In historiography, the early modern revolution in cosmology has long been connected to the Age of Discovery in cosmography. Yet the two things remain conceptually distinct. We can indict Christopher Columbus for the violence of conquest but not Galileo for the discovery of spots on the sun. Yet what if discovery and conquest were conceptually intertwined from the very beginning? The Alchemy of Conquest completely reframes the concept of the Scientific Revolution by taking medieval nominalism and alchemy seriously.

Bauer traces the origins of the categories of discovery and conquest back to the thirteenth-century Renaissance, particularly to the rise of Franciscan nominalism, artisanal alchemical experimentation, and the late medieval spiritual conquest of pagan and heathen souls. Both the alchemical-atomistic conception of matter and the nominalist interpretation of nature led to a voluntarist understanding of divine and human creation. Nature and thus God could be understood not through Aristotelian logic and Scholastic syllogism but through a painstakingly empirical exploration of randomly assembled matter. Universal law could only be known though the careful empirical codification of myriad local laws. The discovery of the secrets of nature happened through violent artisanal extraction and alchemical fire. Artisanal tinkering, in turn, could improve nature.

Such a voluntarist understanding of God’s power and human knowledge of nature led to a voluntarist understanding of religious conversion and to Franciscan global chiliastic religious missions of spiritual conquest. The empirical conquest of both nature and souls (religious transformation) began with William of Ockham, Roger Bacon, Albertus Magnus, Ramon Llull, Arab Aristotelians, and dozens of other artisan alchemists.

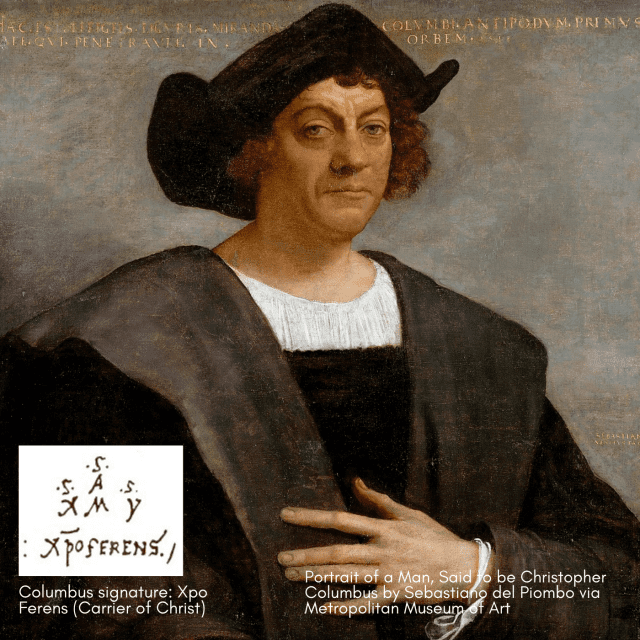

By remapping the medieval conceptual history of discovery and conquest, Bauer’s The Alchemy of Conquest does a number of things. First, it shows the deep alchemical, Franciscan, Llullian roots of Columbus’s ideas of discovery as the artisanal conquest of the occult.

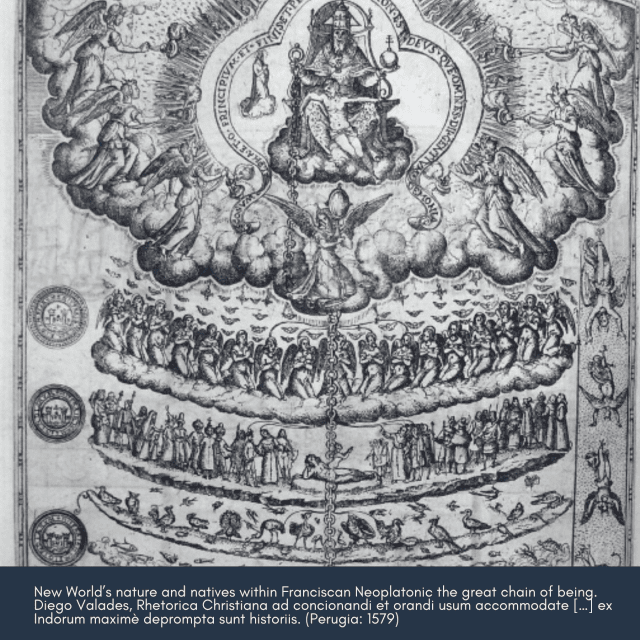

Second, it presents New World missionary Franciscan notions of conversion as tied to alchemical notions of material and spiritual transformations and to demonology and apocalyptic chiliasm. In colonial Spanish America, there was a science of conversion. Religious reducciones (the congregation of natives in towns and missions) did not merely mean social reengineering, as the scholarship on colonial missions and Indian cabildos seems to suggest. Reducción meant a craft, artisanal, and alchemical transformation of the soul via an empirical science of ethnography.

Third, it radically reframes the origins of early modern Epicurean atomism. As Bauer shows, atomism as a commentary on the structure of matter and as a moral-religious discourse of disorderly teleologies first began as a commentary on American cannibalism.

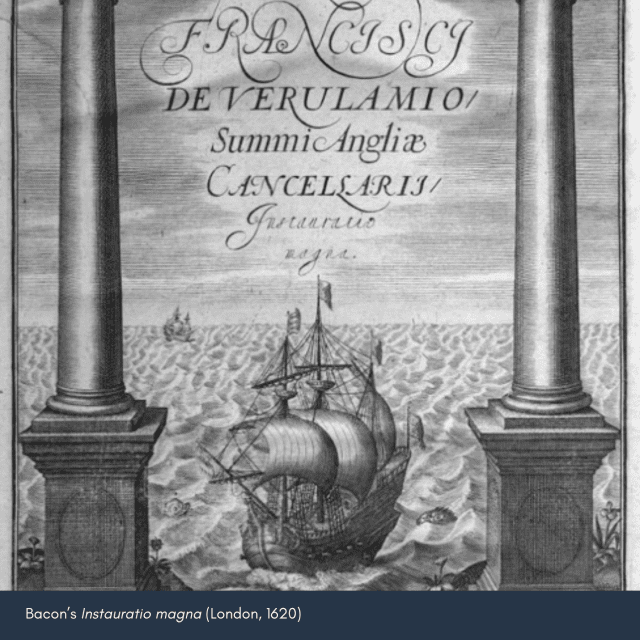

Fourth, the book squarely connects English discourses of colonization to Spanish Franciscan and Spanish Neoplatonic humanist ones (not Spanish Scholastic Dominican ones). English and Spanish interpretations of conquest were connected to alchemical nominalism, demonology, and the natural right to reshape American humans and religious landscapes through craft and conquest. The similarities arose despite the obfuscating English rhetoric of negative contrast (the Black Legend) and England’s outright denial of conquest (the White Legend). Finally, Bauer’s completely reframes Francis Bacon’s new revolutionary empiricism as a deliberate project of applying Spanish alchemical discourses of American colonialism not to peoples but to objects.

This book will remain an enduring accomplishment of scholarship and erudition.

Jorge Cañizares-Esguerra is the Alice Drysdale Sheffield Professor of History, the University of Texas At Austin