On March 24, 1976, a junta led by Jorge Rafael Videla overthrew the president of Argentina in order to install a military dictatorship that they believed would counter the threat of communism . In the seven years that followed, this new government launched a “national reorganization process” or proceso, designed to eradicate Marxist guerillas and their sympathizers. Through censorship and propaganda, kidnapping and torture, and the forced disappearance of tens of thousands of civilians, the state succeeded in subduing insurgents while also taking countless innocent lives. Many scholars have written about this period, known as the Argentine “dirty war,” with emphasis on its most obvious protagonists: the vanquished guerrilla fighters, the military officials, and the radicalized and left-leaning sectors of the population that resisted the government’s atrocious policies at great personal risk.

In his excellent book on this period and the decade preceding it, Sebastián Carassai uncovers the memories and ideological sensibilities of a group that abstained from deliberate political activism during military rule, a sector of the Argentine middle classes that he names the “silent majority.” To highlight variations in the experiences of this heterogeneous social group, the author interviews two hundred middle-class individuals of different ages from three different municipalities: Buenos Aires, San Miguel de Tucuman, and Correa.

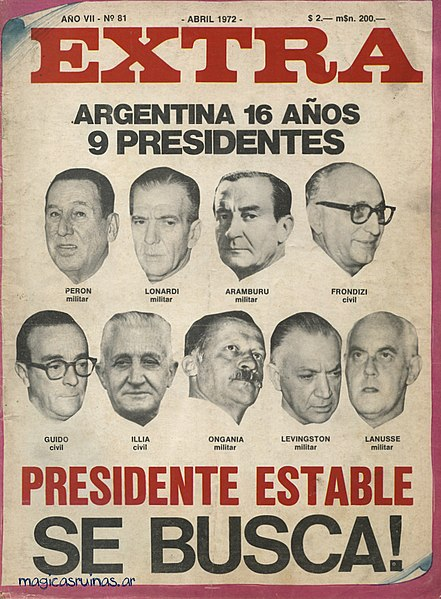

Carassai begins his text by exploring the durable significance of “anti-Peronism,” to middle class political sensibilities. Juan Peron was a populist president who served two terms between 1946 to 1955, and was elected again in 1973. Memories of his administration as a fascist, authoritarian, immoral, and “anti-cultural” regime definitively shaped how Carassai’s subjects engaged with subsequent political events. Perón’s return to power via a landslide electoral victory in 1973 discouraged anti-Perónists to such an extent that many thereafter withdrew from politics entirely.

Beginning in 1969, a series of student-led uprisings against the policies of General Juan Carlos Onganía forced sectors of the middle classes to confront political conflict and state violence. Student demonstrators, many of them young and middle class, were viciously suppressed by police forces, provoking sympathy among Carassai’s subjects. Many of the interviewees remember offering protesters places to hide and items with which to construct barricades. Then, media reports characterizing the young activists as Perónist, subversive, dangerous, and foreign transformed how many middle-class individuals outside of these movements came to perceive student activism.

Source: Wikimedia Commons.

Several left-wing revolutionary factions launched guerrilla campaigns against Ongania’s regime and the administrations that followed. Inspired by the Cuban Revolution, these insurgents employed a variety of methods, including kidnappings and assassinations, in a multipronged effort to overthrow the federal government. Carassai examines how “nonpolitical” members of the middle class perceived these armed insurrections. Refuting allegations that the middle classes initially supported revolutionaries, Carassai points to a frequently overlooked study indicating that a large majority of the middle classes strongly disapproved of guerrilla violence by 1971. A famous soap opera and prominent literature are used as evidence for the silent majority’s growing anxieties regarding the armed revolution. Mounting violence hardened middle-class reproach of the guerrillas, fueling support for state-led repression in some sectors of the population.

The military coup of 1976 heralded a period of repression and terror unrivaled in Argentine history. However, state violence had already existed under the previous administrations, and many middle-class sectors remained hopeful that the new military regime would improve the enforcement of law and order. Carassai cites Michael Taussig’s theory of “state fetishism” to explain middle-class justification for the disappearances of their fellow citizens. The impulse to rationalize state violence emerged from a civil superstition that the state knew who was guilty and who was innocent.

Source: Wikimedia Commons.

Carassai also examines symbolic violence in Argentine culture during the decade prior to the “Dirty War.” Images of guns in advertising evoked positive connotations of status, adventure, and sex appeal. Besides the frequent representations of guns, bombs, and death in magazines, violent metaphors (“liquidation”), slang (“killing it”), and satirical violence proliferated in a manner that trivialized the act of murder within popular culture. Carassai draws upon the theories of Hannah Arendt and Pierre Bourdieu to decipher how this “banalization” of violence explains his interview subjects’ broad acceptance of state terror after 1976.

Carassai employs a huge variety of sources, such as public opinion polls, electoral results, censuses, periodicals, and cultural productions, to illuminate the political sensibilities and memories of his informants. The author’s most impressive contribution, however, is his innovative approach to oral history. After an initial session in traditional interview format, Carassai showed all of his subjects a two-part chronological montage of television clips, popular songs, political speeches, comedy shows, cartoons, advertisements, historical photographs, and news clippings to stimulate their memories of the years being investigated. The images nearly always triggered additional reflections on the events and years depicted. The author’s evident sympathy for his subjects does not deter him from noting contradictions and falsehoods in their testimonies. The book’s main flaw is the absence of any discussion of race, which is a glaring omission when considering the racialized imagery found in many of the cultural products and propaganda that Carassai uses as evidence. Even so, this is a marvelous study of political identity formation, memory, and the cultural origins of violence which should be required reading for all scholars of Argentina’s “Dirty War,” as well as any informed reader interested in Latin America during the twentieth century.

The montage Carassai created and used during interviews can be found at this link:

_________________________________________________________________________________________

The views and opinions expressed in this article or video are those of the individual author(s) or presenter(s) and do not necessarily reflect the policy or views of the editors at Not Even Past, the UT Department of History, the University of Texas at Austin, or the UT System Board of Regents. Not Even Past is an online public history magazine rather than a peer-reviewed academic journal. While we make efforts to ensure that factual information in articles was obtained from reliable sources, Not Even Past is not responsible for any errors or omissions.