by Kameron Dunn

by Kameron Dunn

Sharon Marcus’s The Drama of Celebrity argues that a celebrity is not merely a creation of the media, but is rather a result of the competing interactions between the media, publics, and the celebrities themselves. Marcus makes the provocative argument that celebrities, as we conceive of them today, are not newly minted Hollywood constructions. Rather, they have permeated our social consciousness since at least the mid-nineteenth century with the rise of global theatre and its proliferating media. This is where Marcus situates her history, honing in on the world-famous French actress, Sarah Bernhardt (1844-1923), whose celebrity exemplifies Marcus’s triangulation. Bernhardt’s fans—like all fans—were not merely passive consumers, nor were they obsessive in their adoration as is the popular conception of fandom. Instead, they existed at once in an active and passive state. Marcus does not merely give fans and celebrities pure agency in this process, however. Rather, she illustrates the complex and unpredictable nature of the interplay between these three players in a celebrity’s rise to stardom.

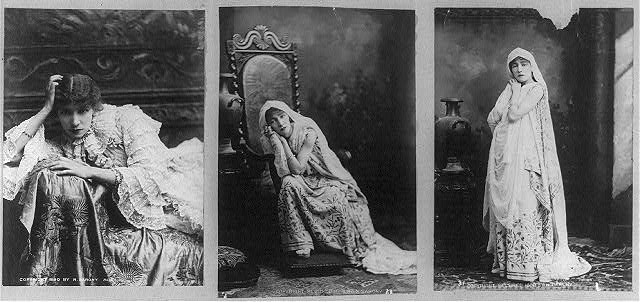

Sarah Bernhardt, 1844-1923, in 3 theatrical poses (via Library of Congress)

To construct her argument, Marcus examines the material culture produced around popular theatre during Bernhardt’s time, especially fan-created scrapbooks. These scrapbooks illustrate Marcus’s central argument about the combined obsessive and passive nature of fandom. Creating scrapbooks was not an entirely passive activity: a fan had to purchase the empty book, collect pictures and paste them in, and arrange the images in a way that suited them. This is clearly not the all-consuming obsession often pinned to a crazed fandom. Most of Bernhardt’s fans operated in this state, as do most fans now.

Marcus shows how celebrities function as “social exceptions,” people who engage in behavior antithetical to social mores but nevertheless secure societal benefits. Publics are drawn to celebrities who defy social convention, who play by their own rules, and who thus satisfy a fan’s internal desire to live uninhibited by the social order. Fans also want to give into celebrities on a more sensuous level. Fandom is created, in part, by a desire to lose yourself in the craft of the celebrity you adore, and to form an identity around the collective experience of celebrity-driven transcendence. Marcus writes: “people want to be moved, even overcome, and paradoxically use their agency in order to lose it.” Bernhardt, for instance, inspired awe on stage in her mastery of the form. Though she performed in French to all her audiences, including American audiences who by and large would not understand her, she played up her physicality in a way that kept audiences rapt. This speaks both to Bernhardt’s skill and to the desires of her fans, who would sit through hours of a play in a language they did not understand just to see her perform.

Sarah Bernhardt by N. Sarony c1880 (via Library of Congress)

For Bernhardt and others, Marcus emphasizes that the media alone do not determine who gets to be a celebrity or which fans will admire them. She shows both the media’s ridicule of celebrities as well as their fans. She situates a particular type of racial and politically-infused ridicule thrown at Bernhardt, primarily through cartoons, that depict Bernhardt as catering to lower-classes of people, such as people of color. Of course, this did not diminish her fans’ adoration, and Marcus makes the point that “[t]he most successful celebrities connect with fans in ways that bypass the media.” This facet of fandom is especially important in considering political figures and the popularity: Trump’s connection with his voter base (insert for “fandom”) remained strong despite media ridicule.

Marcus also shows some of the ways that fans seek intimacy with celebrities. When they take photos, images, or other ephemera and place them in new locations (such as scrapbooks) without significantly changing or altering the media, fans establish their own context and their own personal bonds. Fans of theatre in the late nineteenth century would paste images of actors they liked in a book without any significant additions. Creating the palpable presence of a celebrity in this way is crucial part of fandom. The chapter delves deeper into the ramifications of this desire for intimacy, going further into the eroticizing of stars and attempts for fans to make some sort of in-real-life sexual connection. No matter the degree of affection, the spectrum extends across a fan’s central desire to be recognized by a celebrity they admire.

A star’s ability to make multiples of themselves for their audiences is crucial to their celebrity status, as well. Celebrities cement themselves in the minds of their public by exposing their audiences to their appearance repeatedly and through a variety of media: drawings, photographs, films, etc. It makes sense that with the rise of photography and global communication in the late nineteenth century, Sarah Bernhardt capitalized on her reproduced images to boost her stardom. By “multiplying” themselves, Bernhardt and other celebrities became more recognizable in more guises to more people. This also allows fans to imitate celebrities and their images, mainly through buying products a celebrity advertises or through imitating their fashion. Though ridicule of Bernhardt’s fans was typically restricted to white female imitators, Marcus also takes time to show how the media made this kind of imitation a racial privilege, as demonstrated by cartoons and minstrel performance. In these depictions, Marcus says, “The attempt to imitate celebrities may be universal, but only those at the top of the racial hierarchy are allowed to be seen as successfully copying the stars.”

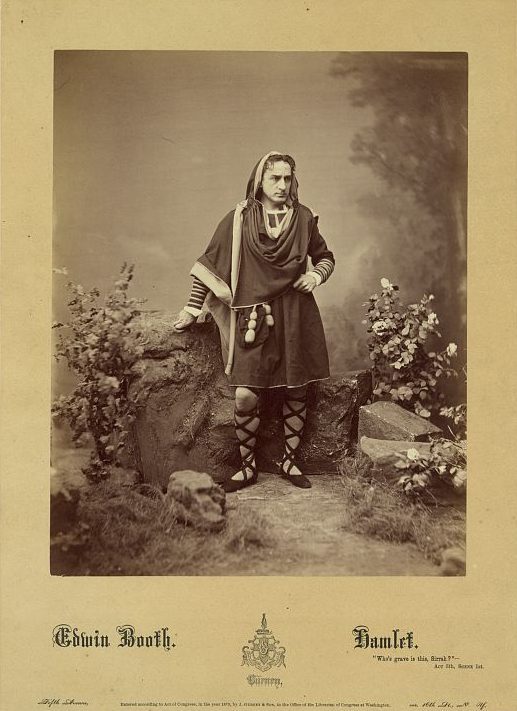

Edwin Booth as Hamlet c1870 (via Library of Congress)

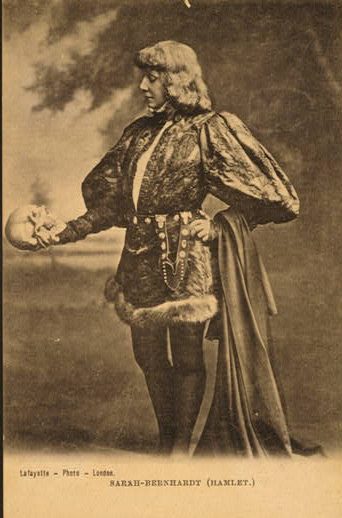

Celebrities and fans are prone to criticism, not just from the media, but from one another as well, and fans critiquing the celebrities they admire is also crucial to creating the intimacy of fandom. Marcus uses the example of fans sending letters to Edwin Booth, the most famous Shakespearean actor of his age, that criticized elements of his acting. Some theatre scrapbooks would also include ranking plays the fan had seen. Marcus also shows that late nineteenth-century audiences would see the same play over and over with different actors and compare their performances in their scrapbooks. Bernhardt played into this tendency. When she played Hamlet, she provocatively claimed that she would outdo the previous male performers of the role. Marcus goes on to discuss the globalizing effect of publics’ ranking of actors across geographic locales. People from all around the world were witnessing the same celebrities and assessing them, putting these disparate communities into a kind of conversation. Marcus shows that fans have a critical role in a celebrity’s rise and in creating a community through that shared experience: a fandom.

For Marcus, celebrity is not created solely by the media. Instead the media, publics, and celebrities themselves all work together to create stardom. However, Marcus is not arguing simply for the agency of fans or celebrities in this process. Rather, she is highlighting the interplay between all three groups in a star-making process that is not as simple—and definitely not as predictable—as one may expect. The most pertinent example here would be the rise of Trump. If we consider Trump’s voter base more like a fandom, we can see how he maintained his popularity despite being panned by the media. Trump mastered his multiples much like Bernhardt and crafted an image of himself that was unmistakably him. His words and actions created an affective response for a voting base disillusioned by the media in general. By Marcus’s calculation, Trump was the perfect candidate for stardom; only this time, his stardom put him in office.

Sarah Bernhardt as Hamlet c 1885-1900 (via Library of Congress)

This book makes a compelling case for seeing Sarah Bernhardt as a model for the history of celebrity and fandom. Marcus’ tripartite theory of celebrity should prove useful for all readers wanting to understand stardom in the past and today, whether celebrities in entertainment, politics, or the often distressingly blurred lines between the two. Readers might wonder how online social media exacerbates the effects of this process. Does it amplify fans, the media, celebrities, or all of them at once? Or does it dampen one of the three? Altogether, Marcus makes a compelling argument that is well-researched, highly readable, and eminently useful.

![]()

You might also like:

History Between Memory and Reconstruction

Dolores del Río: Beauty in Light and Shade, By Linda B. Hall (2013)

Popular Culture in the Classroom

![]()