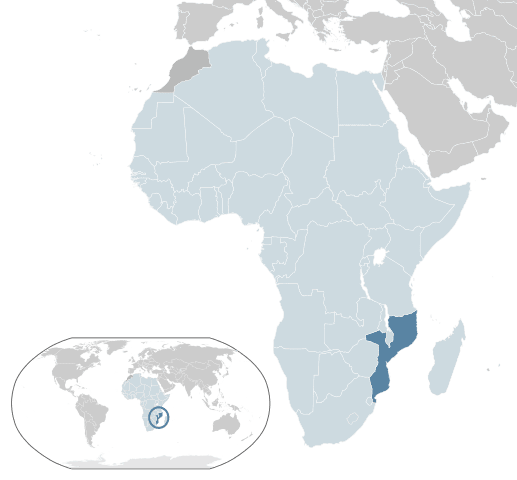

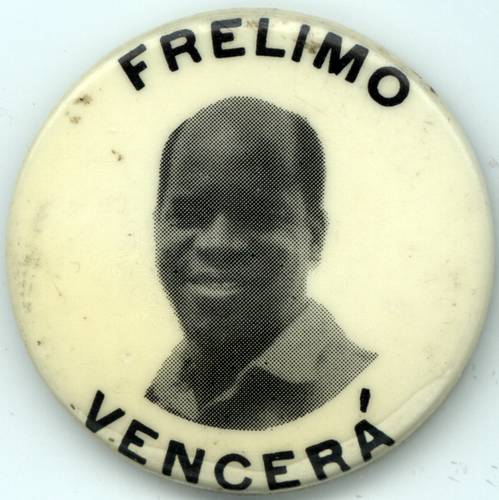

As football returns to living rooms across the United States, it’s worth remembering that the sport has an international appeal for many who have spent time in this country. Fifty years ago this week, one such foreign fan launched a revolution from Tanzania. Eduardo Mondlane, the first president of the Mozambique Liberation Front (Frente de Libertação de Moçambique or FRELIMO), loved American sports, especially professional football. Beginning in September 1964, he guided an armed struggle for the independence of his homeland against imperial Portugal, but he still did his best to make time on Sunday nights to settle in for a game.

Mondlane watched American football games at the Kilimanjaro Hotel in Tanzania’s capital of Dar es Salaam, near where FRELIMO operated its headquarters in exile. The modern glass-clad block is still down the road from the whitewashed façade of St. Joseph Cathedral on the city’s waterfront. In the 1960s, it was a popular gathering place for revolutionaries from across the southern third of the continent – Angola, Rhodesia (modern Zimbabwe), South Africa, and Southwest Africa (Namibia) – which was still under colonial rule. On Sundays, though, Mondlane carved out a little piece of America. Watching football in Africa can still be difficult today, if only due to the time differences. Before satellite transmission made live international broadcasts possible, it was even harder. Physical films had to be delivered by plane from the United States. Each weekend that a game was available, Mondlane would gather with his children and an African American from Chicago named Prexy Nesbitt, who was working with FRELIMO’s propaganda arm on their English-language publication, Mozambique Revolution. Nesbitt remembers that when Mondlane was away on one of his frequent diplomatic missions in the late 1960s, he would ask Nesbitt to keep the tradition going with his children. The determination partly came from Mondlane’s love for American sports– he was a fan of the Cleveland Indians baseball team as well – but there was likely a deeper personal connection. Watching the films on Sunday, even a few weeks after they occurred, connected him with the unique ceremony that is football in America. It maintained a sense of community with the country where Mondlane had been educated and where his wife and children had been born.

Football was just one of Mondlane’s deep ties to the United States. He came from a noble Tsonga family in the south of Mozambique, but he spent over a decade living in Chicago, New York, and places in between. An education at a Protestant mission in Mozambique first took him to the University of Witwatersrand in South Africa until apartheid made further study impossible. His nationalist politics also made it uncomfortable to continue his schooling in metropolitan Lisbon. The United States offered a refuge. Protestant missionary connections and a scholarship from the Phelps-Stokes Fund allowed him to enroll as an undergraduate at Oberlin College. In 1953, he graduated at the advanced age of 32 with a bachelor’s degree, a love of Cleveland Indians baseball, and a passion for the pigskin. He would continue to Northwestern, where he earned a PhD in sociology under legendary Africanist Melville Herskovits. He worked with the Trusteeship Department of the United Nations that was pushing for continued decolonization in Africa, including Portuguese colonies like Mozambique. He even accepted a position as a professor at Syracuse University, resigning only after he was elected president of FRELIMO upon its formation in 1962.

Throughout his time in the United States, Mondlane promoted African decolonization. Even before he graduated from Oberlin, he began making appearances alongside UN officials like Ralph Bunche and humanitarian Albert Schweitzer as an expert on Portuguese Africa. He was active in church circles, where he urged congregations and church camps to expand their interests from domestic civil rights to global political and human rights. Many listeners would take these lessons to heart, including future congressman and Ambassador to the United Nations Andrew Young. In Chicago, he taught university and informal classes, while also speaking to local organizations. Africa stood at a crossroads, Mondlane would explain to his audiences, and it was up to progressive forces in the United States to support its bid for independence against outdated colonialism. Only this international pressure could force Portugal to finally give up her colonies without the need for armed revolution. The nonviolent message would link Mondlane with the emerging Civil Rights movement. Longtime National Urban League head Whitney Young knew him well, and he attended the first American Negro Leadership Conference on Africa organized by Martin Luther King, Jr. and James Farmer. Those who met him remembered him as intelligent, personable, congenially authoritative, and utterly convincing.

Mondlane’s ties to the United States were extensive, but his strongest by far was his marriage to Janet Rae Johnson of Downers Grove, Illinois. Mondlane met his future wife at a church summer camp, and they began a lengthy correspondence. She was part of a generation of young Americans whose religious convictions pushed them to agitate for racial equality, but her interests were more global. Janet Mondlane became a partner for Eduardo in much more than a domestic sense, sharing his commitment to self-determination for Mozambique. The marriage was controversial – Janet was not only white but nearly fourteen years younger than her husband – but they were nothing if not determined. Janet and their growing family joined Eduardo in Dar Es Salaam when he moved there to direct the exile movement. The white Midwesterner became the head of the fundraising arm of FRELIMO known as the Mozambique Institute, which ran a secondary school for refugees. Her powerful position angered some within the party due both to her race and gender, but she became an important element in selling FRELIMO’s cause to the wider world.

Portugal was part of the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO), and in the midst of the Cold War it used anti-communism to justify fighting a war to retain its colonies. Western allies disagreed with Portugal’s approach to its colonies, but they were not willing to put decisive pressure on the government in Lisbon. After FRELIMO decided on the course of armed revolution, it depended on weapons from neighboring African countries, China, and communist Eastern Europe, but it did not want to choose sides. The Mondlanes knew that there were many in the United States and Europe who sympathized with their cause and they worked to cultivate these relationships. Eduardo Mondlane’s cultural fluency and vision of a free Mozambique made a good impression on Robert Kennedy in 1963, which led to the Ford Foundation donating tens of thousands of dollars to the Mozambique Institute. But such government aid to a revolutionary movement was unpopular and unusual since it targeted an ally. FRELIMO relied more on building relationships with civil society groups, which included religious organizations and young people frustrated by the Cold War. Popular movements would eventually develop throughout the Western world, holding political rallies, launching boycott campaigns, conducting clothing drives, and raising funds to support the social programs of FRELIMO and the Mozambique Institute. In Europe especially, these movements would grow in strength until they convinced governments and political parties in places like Sweden, Norway, the Netherlands, and even Britain to directly aid the liberation parties. The Mondlanes and FRELIMO cultivated these unofficial friendships through a shared commitment to self-determination, but also through personal connections like those formed with Prexy Nesbitt. Effective transnational diplomacy depended as much on talking about local concerns and personal passions – like Chicago football – as talking African freedom.

Frelimo button with the face of Eduardo Mondlane, the first president of the movement. Translation: ‘Frelimo will win’. Image via African Activist Archive at MSU

Eduardo Mondlane would not live long enough to see the independence to which he had dedicated his life. He died in 1969 after opening a parcel bomb mailed to him in Tanzania. Janet Mondlane remained active in the struggle and continues to live in Mozambique today. She and FRELIMO maintained her husband’s diplomatic neutralism after his death and oversaw the expansion of Western support, even as they used African and communist supplied weapons to fight Portugal to a standstill and gain independence in 1975. Neither in Mozambique nor in those American institutions that he touched has Mondlane been forgotten. In a tribute published in Mozambique Revolution in February 1969, one party member observed that “he was able to speak for us the language of other men – the language of the diplomats, the language of the universities, the language of power.” On Sundays, he would also speak the language of American football, illustrating the transnational linkages that can create a sense of community between the United States and the world but too often pass unnoticed or unremembered.