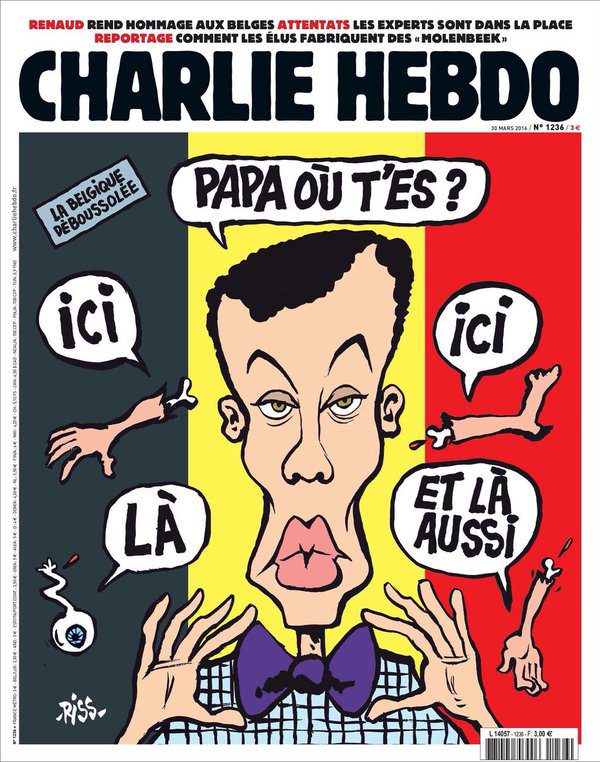

In 2013 Belgian musician Paul Van Haver (AKA Stromae) released a powerful music video called Papaoutai (Where Are You Dad?), which by now has been seen more than 300,000,000 times on You Tube alone. The lyrics go:

Where is your dad?

Tell me where is your dad?

Without even having to talk to him

He knows it’s not going well

Oh my dear father

Tell me where are you hiding?

I must’ve counted my fingers at least a thousand times

Where are you dad?

Where are you dad?

Stromae has nothing to do with ISIS or with Muslim migrant communities in European suburban ghettoes. He is originally from Rwanda and having lost his father to the genocide wrote a painful song about the absence of the father. However, the “death of the father” and the otherwise absence of living fathers who are psychologically broken is such a common reality in migrant communities that it immediately captured the attention of youngsters whose parents were struggling to make a positive impact on their lives. Capturing the pain associated with the dysfunctional family unit, the humiliation of the father-figure and the absence of positive role models of authority, Stromae unintentionally accounted for the social reality that pushes migrant kids to the hands of ISIS and fuel their desire for violent revenge.

When it comes to Islamic fundamentalism and inter-Arab politics, the influential Palestinian journalist Abdel Bari Atwan, has seen it all. Since the 1980s he carefully documented the slow metamorphosis of a young Arab generation that came to believe that it had nothing to lose at home and everything to gain from a festival of death and glory in the distant mountains of Afghanistan. They had their rationale, of course, but as Atwan concluded already back then, rationality was not the name of the new game. Yes, along the way, there was the famous 1996 interview with Ussama bin Laden when, after a night in a cave with the tall man, and two years before anybody in America cared to know what al-Qaida was, he realized that much more was to come. He kept with it ever since.

But the strength of Atwan’s reporting is not predicated on his remarkable ability to get a high-profile interview. It’s his intimate attention to the rank and file members of the fundamentalist organizations. The small stories, the casual chit-chat with an ISIS fighter on transit from Europe to Syria and Iraq, the arcane Arabic language manuals that call for a new type of shock and awe violence, his ear for gossip and inside information and, ultimately, the ability to reconfigure all of this seemingly unrelated data into a more or less coherent picture. His Islamic State: The Digital Caliphate is not a perfect book. It was brought to the market in haste and suffers from dubious editorial decisions, gaps in narrative, redundant political pontification, and bad copy editing. Yet, if you are willing to forgive all of these, you will be treated to a fascinating tour of ISIS’s crooked world.

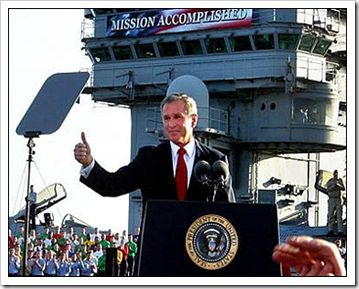

The story of ISIS calls for a long view. The history of the organization, its genocidal culture, its obsession with sexual violence, and its overall rise to prominence makes absolutely no sense without considering the traumatic history of Iraq since the early 1980s. A sustained legacy of state torture, daily violence, international sanctions, starvation, and profound existential insecurity left thousands of Iraqis dead and millions in a state of loss and constant fear. Numbers such as 1.7 million Iraqi dead, among them 500,000 children during the Western sanctions of 1990s alone, cannot even begin to account for the horrors of this place. Under Sadam Hussein’s reign of terror, families were broken up and almost every citizen experienced some level of abuse and exposure to physical or psychological violence. Compounding the impact of the horrendous Iran-Iraq war (1980-1988), Iraq’s population was on the verge of total collapse. This dramatic situation reached its apex in the wake of the 2003 American invasion. In between these two extremes of history, Sadam’s accession to power and the American invasion that removed him, one can find the circumstances that are responsible for the pathology of ISIS.

The year of the US invasion, 2003, was especially destructive. The sudden disappearance of an oppressive and centralized bureaucratic and military apparatus supported by Sunni tribes left thousands of able and now embittered men in the cold. More than 50,000 of them automatically joined a Sunni-oriented insurgency against the Americans and what seemed to be their Shi`i allies. The so-called “surge” of 2007 largely demolished this front. With its affiliate members dead, incarcerated or scattered, a new cycle of violence was ready to begin and a host of al-Qaida compatible organizations were there to exploit the mayhem. They promised revenge, redemption, and rebirth through extreme violence and radical self-fashioning. They could reason with both tribes and former regime members. They spoke the language of Sunni triumphalism and promised to address the unjust politics of Iraq and the victimization of its once powerful political majority. ISIS is of this environment and, given the weakness of the Iraqi state, its rise into a significant force is neither surprising nor particularly new. It’s simply a continuation of Iraq’s impossible reality by different means.

And the means do matter. Tracing the story of Abu Musab al-Zarqawi can tell us why. In 1989 al-Zarqawi left his hometown in Jordan and joined al-Qaida in Afghanistan. The prospects of organized Jihad in Jordan were always grim given this country’s efficient security services. After 9/11 when the Americans decimated al-Qaida’s Afghan operations, al-Zarqawi and a few hundred warriors slowly made their way westward through the mountains, rivers, and plains of Afghanistan and Iran toward the new opportunity that Iraq had to offer. Though he endured prison and abuse in Iran, al-Zarqawi did eventually make it to Iraq where, just as in Afghanistan, he set up a Jihadi training camp, forged relationships with Sunni tribal leaders, and joined the anti-American insurgency as an al-Qaida affiliate. So far there was nothing unique about this trajectory.

But al-Zarqawi was not in Iraq in order to establish another mainstream front. He was there to make a bigger impact. And so, during the particularly bloody year of 2005-6 al-Zarqawi branded a signature style of violence that was so gruesome and so counter-intuitive that it shocked even his allies in al-Qaida, who dismissed him from their ranks. Under his leadership, violence turned death into finely produced media spectacles for mass consumption. Captured on video and edited with a new kind of Jihadi sound-track, or nashid, ritualistic beheadings, mass-suicide bombing against innocent shi`is, and multiple other acts including the unbelievable bombing of a Palestinian wedding in Jordan, became hip-clips for mass consumption. Al-Zarqawi was the first to conscript female suicide bombers, the first to marry Jihad with snuff culture and the first to initiate a violent modus operandi that had absolutely no operational logic behind it. Confusing the means and the ends, violence for its own sake perpetuated itself with no need for justification, no concrete plan, and no end in sight. In 2006 an American drone finally got al-Zarqawi. The man died on the spot but, in a land of trauma, his legacy was destined to have a life of its own.

As Atwan shows, at about the same time, this new radical practice of violence found its theological justification in the form of two new Jihadi texts, The Management of Savagery (2004) and The Global Islamic Resistance Call (2004). Both texts were a response to the bravado of America’s Shock and Awe campaign in Iraq. These counter-texts proposed a simple and cheap strategy to horrify the West without the need for any sophisticated weapons. A sword, a camera and a You Tube account would suffice. In their long mediation on the subject, both authors used an ad-hoc manufactured Islamic jargon that provided the false impression of Islamic authenticity, high-mindedness, and scholarly legitimacy thus hiding the made-up and superficial nature of this form of Jihad. Both texts laid out a vision of an apocalyptic violence, after which peace would rule the lands captured by the Islamists. Time and again, mainstream jurists and key religious figures who vehemently oppose such manipulation of the religious heritage proved too weak or slow to react effectively. It is obvious that public religion was in crisis and that these developments constituted a revolution within Islam more than a revolution of Islam against an outside force. Indeed, most victims of the “new violence” were Muslims themselves.

Al-Zarqawi’s legacy and the proliferation of savagery for its own sake was amplified and systematized by the 2006 establishment of an umbrella organization of several smaller Islamic insurgency groups under the banner of the Islamic State in Iraq (ISI). In the wake of the Surge, the Sunnis who used to run the civic and military institutions of the Iraqi state as well as a collation of Sunni tribes felt increasingly marginalized and under attack by the majority Shi`i leadership and its tight control of the state’s security services. The leaders of this coalition, almost without exception, had experienced abuse, incarceration, and torture, some of it at the hands of the Americans. To add insult to injury, in the aftermath of the Surge, the Iraq’s Shi`i President, Nuri al-Maliki, decided to disassemble the 54,000 strong-man Sunni militia that the Americans put together in order to fight the Sunni-Islamist insurgency. This disastrous move betrayed the sectarian agenda of those ruling Iraq thus automatically providing ISI with a major infusion of personnel and material. ISI was now ready to take on the Sunni areas of Iraq. The 2011 American withdrawal from Iraq and the beginning of the civil war in Syria provided a rare opportunity to connect the two fronts and envision a historic caliphate.

In the annals of the region, the border that separated Iraq from Syria was always seen as an artificial imposition of French and British colonialism. Over the decades there were several attempts to undo such borders. ISI had an opportunity to do something about it that was not only of huge symbolic value but also operationally smart. Beginning in the summer of 2013, they expanded inside Iraq and westward toward Syria where they absorbed and coerced several Islamic oppositional groups to join them or face the choice of annihilation. This gang politics made their Syrian operation successful. A capital was established in Syria’s provincial center of Raqqa and the letter “S” was added to its acronym. The ISI became ISIS (Islamic State in Iraq and Syria) as the infrastructure of two broken states was up for grabs. In a matter of months ISIS was in control of banks, hospitals, police stations, military installations, schools, power plants, dams, canals, bridges, oil fields, refineries and even a chemical weapon program to name a few of their most famous spoils. The amount of military material that they now owned made them a considerable force to reckon with, more mobile, agile, and vicious than the American-trained Iraqi forces who shamefully retreated at the outset of any significant engagement.

Equipped with state infrastructure and the euphoria of expansion, the idea of the Islamic state as a purist religious community and alternative to the failed ethnic nation-state, gained traction. They called it the caliphate, thus reviving an institution that was abolished by the Turkish government in 1924 and left the Islamic world without a symbol of sovereignty. They also found a caliph: a mediocre religious scholar, a former US prisoner, a brilliant organizer, and a charismatic leader. In July 2014, Ibrahim Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi was sworn in as the new Caliph in the newly captured city of Mosul. He now presided over a huge organization that had strong inter-tribal backing as its backbone, a skeleton of a state, and a murderous fighting machine.

Though Atwan does not dwell on the internal organization of the Islamic State, recently captured ISIS documents reveal that an exceptional amount of energy is invested in streamlining the daily operation of the state. These include highly detailed and specific procedures for running hospitals, food distribution networks, and newly established education, justice and fiscal systems. Multiple social policies that aim to facilitate the marriage of ISIS members and the well being of their young families were put to work as well. Establishing a utopian community that is predicated on a metaphysical escape from the present, or a “return” to the unadulterated grandeur of classical Islam in the seventh century, is a powerful form of mass dissociation. It was also an effective tool of recruitment. ISIS created a magical community of teenagers that is the subject of generous divine benevolence, in which everybody is a “brother” and a “sister.” In a decades-long social environment of broken families and compromised father figures, ISIS is functioning as an alternative family that bestows on its members a false sense of authenticity, historical continuity, a measure of sovereignty, self-reliance and, most importantly, faux dignity and self-worth. In offering such an ephemeral identity, it delivers much of what post-colonial Arab societies failed to deliver. And it does so not only for the inhabitants of the Middle East but also for Europeans.

So powerful is the allure of this new community that second and third-generation Muslims in Europe, whose North African parents were destroyed by colonialism, immigration, poverty, and cultural marginalization, flocked to its ranks. Thirsty for acknowledgment, belonging, action, and a sense of control over their destiny, French, Belgium and British Muslims, to name a few, joined ISIS by the thousands. Indeed, the phenomenon of ISIS cannot be understood without delving into the parallel ghetto experience of many Muslim communities in Europe. Six decades after it officially ended, the residues of European colonialism are still at play. Atwan tells the story of several key activists and Jihad-tourists, one of whom is an American, who left their loving families behind and took managerial positions in the caliphate. The overwhelming majority who had no special skill to offer besides their bare life, were enlisted as Jihadists.

As the book’s subtitle suggests, a major theme that sets ISIS apart from the analog and insulated leadership of al-Qaida, is the instantaneous electronic nature of this so-called cyber caliphate. In contrast with al-Qaida and similar 20th century organizations, ISIS has a sophisticated media and digital arm that generates twitter storms, maintains an ongoing presence in chat-rooms, and uses a variety of coded means to communicate with its young audience outside Iraq and Syria. Employing programmers and code specialists, ISIS generates hundreds of hacking attacks against a long list of personal and institutional enemies, most of which are in Europe. A short distance, Atwan skillfully shows, separated Junaid Hussein, the British hacker of former British premier Tony Blair’s personal email account, from enlisting in ISIS as chief technological officer. It’s a small world.

Above all, ISIS in a community of organized violence, much of which takes place under the influence of the amphetamine Captagon, which is not new to the region and is cheap and easy to manufacture. Besides the systematic and exhibitionist destruction of universal heritage from Ancient Nineveh to Roman Palmira, ISIS’s most ubiquitous mode of operation is rape. Sexual violence is a feature of many wars. Remember, for example, the Soviet takeover of Berlin in WW II and its aftermath. Yet, in contrast with armies that commit such human rights violations separate from their military mission, ISIS’ obsession with sex is constitutive to its core mission. War and rape, rape and war collapse into each other to the degree that the military mission and the theologically justified spoils of war (unbridled access to women), become one and the same. The ownership of slave girls and their repeated rape is encouraged, desired, and legally justified. The promise of unrestrained sex is a further tool of recruitment.

Taken as a whole, Atwan’s ISIS differs from the portrait drawn by most Western writers. Whereas most foreign observers approach ISIS through the prism of Islamic fundamentalism and see religion as its main element, for Atwan ISIS is nothing but a gang whose gang culture is superficially justified by resorting to a distorted form of Islam. It’s a fundamental difference that allows the Palestinian journalist to take account of the broken history and severe circumstances that made the theater of ISIS possible while seeing in religion a mere prop rather than a the play’s script. Whether one agrees with this take on ISIS or not, one thing is clear. Though ISIS’ days as a unified political and military machine might be numbered, the fallout from its inevitable collapse is going to be prolonged, global and violent.

Abdel Bari Atwan, Islamic State: The Digital Caliphate (University of California Press, 2015)

Charlie Hebdo image: here

All other images: Public Domain