An earlier version of this review was published on halperta.com.

Ticha means “language” in Zapotec, an Indigenous language spoken in the state of Oaxaca, in southern México. The digital platform, Ticha, offers a corpus of Colonial Zapotec documents, many thought to be lost or inaccessible, and a variety of ways to explore and study them. It is an ongoing project led by an interdisciplinary team of scholars from different fields in the United States and México and is supported by Haverford College Libraries: Brook D. Lillehaugen, Linguist-Assistant Professor, at Haverford College (http://brooklillehaugen.weebly.com/); George A. Broadwell, Linguist, Professor at University at Albany (SUNY) (https://www.albany.edu/anthro/broadwell.php); Michel R. Oudijk, Ethnohistorian, Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México (https://mroudyk.weebly.com/index.html); and Laurie Allen, Coordinator for Digital Scholarship and Services at Magill Library, Haverford College.

The digital platform itself is organized into three main areas: The Project, Colonial Zapotec Language, and The Texts. The first section, “The Project” provides an introduction to the Zapotec language and a general overview of the project. It also explains the encoding data for Ticha from a linguistic approach. The following computer programs were used: FLEx which is Fieldworks Language Explorer, a system for lexical and grammatical analysis, and Text Encoding Initiative standards for paleographic and translational representations of texts.

At the bottom of the introductory page, videos present the people on the team, which allows users to understand the motives of the authors and the processes used in the project. This personalized approach is furthered with the Contact Us section on the About page that allows users to subscribe for e-mail updates and give comments and suggestions to the team. The opportunity to provide feedback to an emerging digital project encourages a space for dialogue with primary texts.

The section on the Colonial Zapotec language presents linguistic background about the many varieties of Zapotec and its current usage in the State of Oaxaca, México, and the United States. This page explains that the variety of Zapotec found in Ticha, which is referred to as Colonial Valley Zapotec, dates to the colonial period of México from (1521-1821). The second part of this section presents the cultural context, which situates Ticha’s texts in the broader colonial history of México. Christianity played an important role in the religious conversion of Indigenous populations and therefore Ticha includes an expansive documentation of these languages that resulted in dictionaries, grammars, and religious works. The page further explains the importance of Ticha as “a window for contemporary indigenous communities and scholars alike to explore Zapotec history, language, and culture.”

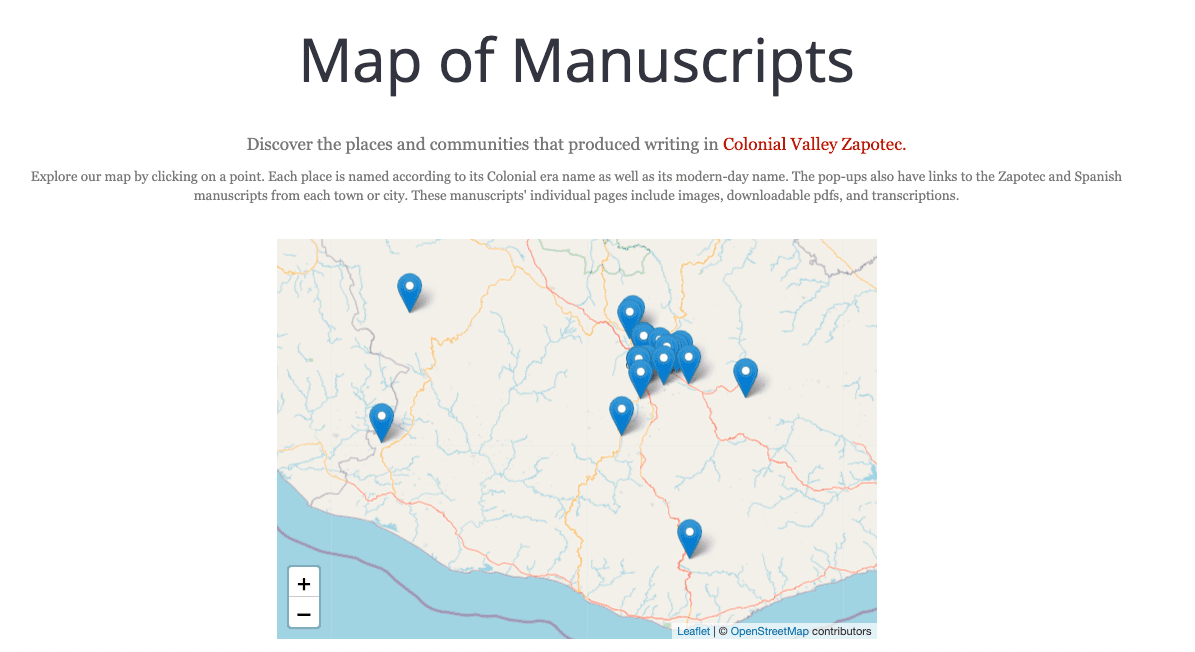

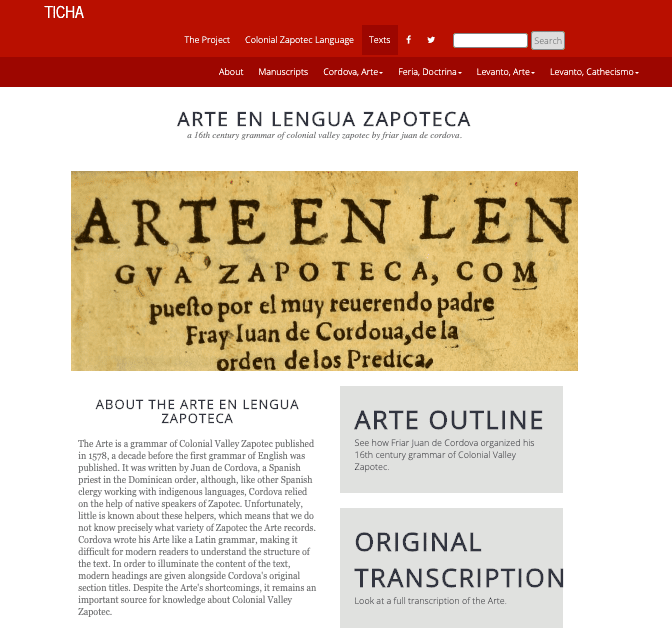

The corpus of Zapotec-language texts presented on this platform, in the section “Texts,” is from the colonial period and is comprised of three primary sources, all of which originated in the Central Valley Zapotec, Oaxaca. The page is divided into three main parts: Arte en lengua zapoteca, Doctrina christiana en lengua castellana y çapoteca and Handwritten texts.

The first, Arte, is a sixteenth-century grammar of Colonial Valley Zapotec by Dominican Friar Juan de Cordova with the help of unrecognized Zapotec speakers, which aims to describe the grammatical structure of Zapotec. Based on the historical context, it can be deduced that the grammar book was used to document the language for conversion purposes. This Zapotec grammar follows the structure of a Latin grammar, difficult to understand but it provides knowledge of the Colonial Valley Zapotec language. This section provides the following materials: an outline of Arte en lengua zapoteca created by George Aaron Broadwell, Victoria Kranz, Brook Danielle Lillehaugen & Michel R. Oudijk with Laurie Allen & Enrique Valdivia in 2014. Followed by a PDF version of the text, a transcription of the whole grammar book, a version of the grammar book in regularized Spanish, and a sample page of the work Ticha is working on. Finally, the sample page provides an image of a page from the original text on the left side with three tabs on the right side that link to a transcription of the original text, and a translation into modern Spanish and English.

The second is a religious Zapotec text from the year 1567, Doctrina christiana en lengua castellana y çapoteca written by Dominican Friar Pedro de Feria with the help of native Zapotec speakers, which is not recognized in the text itself. The Doctrina consists of 233 pages, each with a column of Spanish on the left and Zapotec on the right. This Doctrina was used to explain Catholic doctrine and it provides Zapotec syntax and semantics, and culturally exposing the religious belief of that time. For the Doctrina christiana en lengua castellana, one finds the complete PDF version of the text and a sample page with an image of the original text, and a transcription of that same page.

The third set of materials presented are fifty handwritten texts, twenty-nine in Zapotec and twenty-one in Spanish, all organized by name, year, town, archive, type of document and language. These texts were written by native Zapotec speakers in the Zapotec language as well as in Spanish. The topics treated in these manuscripts include religious issues, testaments, wills, deeds, and letters. This section provides all of the fifty manuscripts with the following metadata: name of the document, year, town, archive, type of document and language. There is also a sample manuscript that includes an image of the original version in Zapotec and Spanish, and transcriptions from the primary source to standard Romanized alphabet in Zapotec and Spanish. The last part in this section consists of a timeline of the Colonial Valley Zapotec Documents from 1633-1840 with their respective town name and coded as: Zapotec Testament, Zapotec Bill of Sale, Contemporaneous Spanish Translation, and Other.

Ticha is primarily targeted to an academic audience in fields such as history, anthropology, linguistics, cultural studies, and anyone who is interested in colonial Zapotec. This platform was also created for the Zapotec community. For instance, in one of the videos, Janet Chávez Santiago, a Zapotec teacher from Teotitlan del Valle, Oaxaca stated the engagement and excitement from her students when comparing modern Zapotec to colonial Zapotec.

In their essay, “Los archivos y la construcción de la verdad histórica en América Latina,” Carlos Aguirre and Javier Villa-Flores discuss the ways that the archive legitimizes forms of authority and credibility. In thinking about the colonial histories and the political agenda of the monarchy in Spain to maintain order and use the archive for their own political and economic benefits, the same pattern of destruction and stealing of the archive continued to appear in post-independence governments (9-10). In this political context, the archive has been used as a weapon to exercise power; yet it is also important to note, as Eric Katelaar does, that these same documents can be used as, “instruments of empowerment and liberation, salvation and liberty (instrumentos de empoderamiento y liberación, salvación y libertad).” Ticha is a venue that provides availability and accessibility of colonial texts that strengthen their language and their culture.

Digital technology plays an important role in supporting access to the Colonial Valley Zapotec archive. Ticha is serving both academics and the Zapotec community who are studying the language, culture, and history. The interactive, easy online access Ticha provides is changing the way that Zapotec community members have perceived archives in the past. No longer are they considered untouchable or inaccessible, as stated by Janet Chávez Santiago “with one click they are on Ticha and they can see these documents and that’s something I really like about Ticha because I can share.” Ticha connects the past to the present, to generate dialogues that center the future of the Zapotec community. This project shows how the digital archive has developed to serve different audiences, reflect several voices in the archive, and emphasize a sense of reciprocity with the Zapotec community.

References:

- Aguirre, Carlos, and Javier Villa-Flores. “Los archivos y la construcción de la verdad histórica en América Latina”. Jahrbuch für Geschichte Lateinamerikas – Anuario de Historia de America Latina 46.1: 5-18. PDF.

- Chavez Santiago, Janet. Video on the Educational Value of Ticha. Haverford College. https://ticha.haverford.edu/en/about/

- Katelaar, Eric. “The Panoptical Archive”: Francis Xavier Blouin/William G. Rosenberg (eds.), Archives, Documentation, and Institutions of Social Memory: Essays from the Sawyer Seminar (Ann Arbor 2007), pp. 144–150. PDF.

- Lillehaugen, Brook Danielle, George Aaron Broadwell, Michel R. Oudijk, Laurie Allen, May Plumb, and Mike Zarafonetis. 2016. Ticha: a digital text explorer for Colonial Zapotec, first edition. Online: http://ticha.haverford.edu/

You Might Also Like:

Spanish Flu in the Texas Oil Fields

Más de 72: Digital Archive Review

Making History: Houston’s “Spirit of the Confederacy”

Rising From the Ashes: The Oklahoma Eagle and its Long Road to Preservation

Authorship and Advocacy: The Native American Petitions Dataverse