On the surface, Train Dreams appears to be an historical novel; most of the story takes place during the first third of the twentieth century, and it includes real people and places. Yet as a narrative, the novel—or rather, novella (consisting of 116 short pages)—is fundamentally ahistorical. The protagonist Robert Grainier lives for 80 years, but he remains outside the mainstream of American life; when he dies, he has never used a telephone. He has no heirs, and he has no personal history before the time he can remember as a boy. He never learns anything about his parents or the place of his birth, and in fact he “soon misplaced this earliest part of his life entirely.” Thus he lacks a sense of his own beginnings.

Grainier suffers a great tragedy in mid-life, and that tragedy shapes his subsequent being in the world, but he does not seem to change much as a person; throughout the book he remains a skinny and steady hard worker, and though we feel for him in his loneliness, we do not learn much about him as a person. The book is not organized chronologically, and from start to finish certain constants endure—Grainier’s encounters with the menacing magnificence of nature in northern Idaho, and with the “the hard people of the northwestern mountains”—his people—who live there. Johnson highlights the railroad as a metaphor and as a source of employment for Johnson, but it is not a machine that takes us from one place to another; rather, its whistle blends with the howl of the coyote, and as it passes through the valley where Grainier lives, it enters his dreams.

Grainier suffers a great tragedy in mid-life, and that tragedy shapes his subsequent being in the world, but he does not seem to change much as a person; throughout the book he remains a skinny and steady hard worker, and though we feel for him in his loneliness, we do not learn much about him as a person. The book is not organized chronologically, and from start to finish certain constants endure—Grainier’s encounters with the menacing magnificence of nature in northern Idaho, and with the “the hard people of the northwestern mountains”—his people—who live there. Johnson highlights the railroad as a metaphor and as a source of employment for Johnson, but it is not a machine that takes us from one place to another; rather, its whistle blends with the howl of the coyote, and as it passes through the valley where Grainier lives, it enters his dreams.

From a historian’s perspective, the greatest virtue of Train Dreams is its evocation of the rough life followed by railroad construction workers and lumbermen in the Pacific Northwest. As a young man Grainier spends time as what he calls a “layabout,” but what we today would call a casual worker. He helps to blast tunnels, bridge canyons, cut trees, and roll logs. He embraces outdoor engineering feats as intrinsically heroic, hailing the spanning of a 60-foot deep, 112-foot wide gorge akin to building the pyramids. He and his co-workers “fought the forest from sunrise until suppertime,” and then collapse, exhausted, into their bunks.

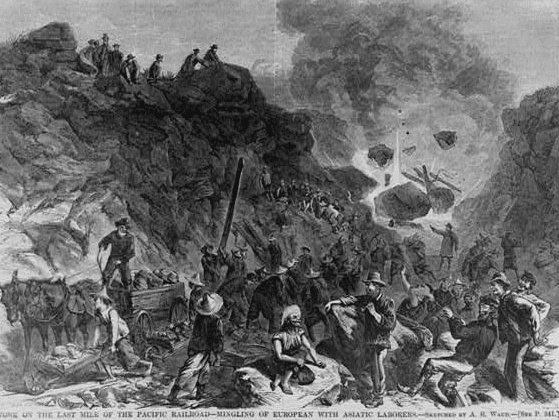

An 1869 sketch depicts men Working on the last mile of the Pacific Railroad. European and Asian laborers mingle together. (Image courtesy of the Library of Congress)

An 1869 sketch depicts men Working on the last mile of the Pacific Railroad. European and Asian laborers mingle together. (Image courtesy of the Library of Congress)

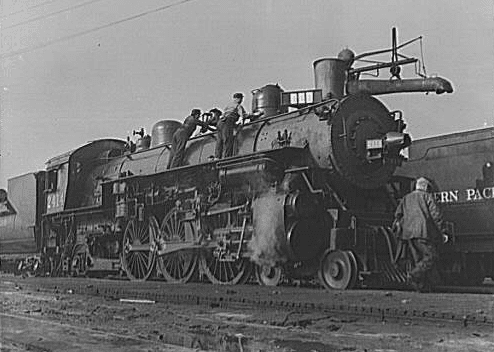

Railroad workers for the Southern Pacific Company in San Francisco. (Image courtesy of the Library of Congress)

Railroad workers for the Southern Pacific Company in San Francisco. (Image courtesy of the Library of Congress)

By the time he is in his late 30s Grainier is making and saving money to care for his wife Gladys and their daughter Kate, whom he regularly leaves in their valley cabin for months at a time while he seeks work wherever he can find it. Returning from a railroad job in the fall of 1920, he sees that a fire has consumed the valley and that Gladys and Kate have vanished: “Soon he was passing through a forest of charred, gigantic spears that only a few days past had been evergreens. The world was gray, white, black, and acrid, without a single live animal or plant, no longer burning yet full of the warmth and life of the fire.” Devastated by the loss of his family, Grainier slowly rebuilds a cabin on the site of the old one, and lives isolated from the rest of the world, as long as his savings sustain him.

Juxtaposed to the tenderness Grainier feels for his family is the deep and persistent violence that Johnson presents as a fundamental fact of rural western life. The author punctuates his story by accounts of horrific deaths—a lumber worker killed by a falling tree branch; a 12-year old girl murdered by her father when he discovers she is pregnant (unbeknownst to him, raped by her uncle); an Indian run over by a train, his remains scattered in tiny pieces along the track; a teen done in by a weak heart while lifting a sack of cornmeal; a prospector blown to bits while trying to thaw out a stick of dynamite on his wood stove.

Southern Pacific Company railroad yards in San Francisco. (Image courtesy of the Library of Congress)

Southern Pacific Company railroad yards in San Francisco. (Image courtesy of the Library of Congress)

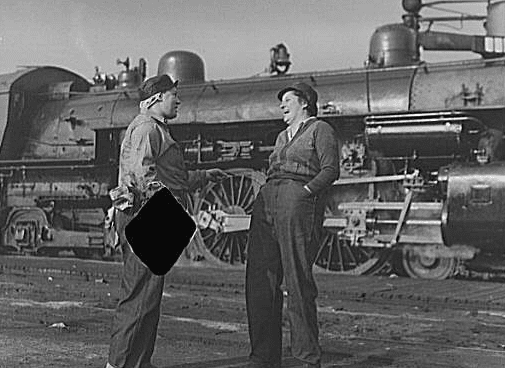

Women railroad workers take over the cars and maintenance of freight and passenger trains in the Southern Pacific Company yards at San Francisco. (Image courtesy of the Library of Congress)

Women railroad workers take over the cars and maintenance of freight and passenger trains in the Southern Pacific Company yards at San Francisco. (Image courtesy of the Library of Congress)

Gladys appears as a ghost to tell her widowed husband the circumstances of her own painful demise; in fleeing the fire with Kate she fell onto rocks in a river, breaking her back. The rushing waters bore her away. Train Dreams contains other elements of magical surrealism—think Toni Morrison flirting with Paul Bunyan–mainly as a means of melding humans and animals into a single life-force that animates the mountains and valleys. After years of living alone, Grainier hears terrifying stories of a “wolf-girl,” half person and half beast, who roams the land with no other apparent purpose than to strike fear into hearts of grown men: She was “a creature God didn’t create. She was made out of wolves and a man of unnatural desires.” Predictably, this wolf-girl turns out to be Grainier’s long-lost daughter Kate, though the first and only time they confront each other, she shows no recognition of her father, and quickly disappears forever into the forest. To mourn, Grainier howls with the wolves, his lament echoing off the mountainsides.

One of the great pleasures of Train Dreams is the evocative language Johnson uses to describe the brutality of entwined natural and human forces. A group of white men grab and try to lynch a Chinese railroad worker accused of stealing, but the attackers are at least momentarily thwarted when their victim “shipped and twisted like a weasel in a sack, lashing backward with his one free fist at the man lugging him by the neck.” Grainier finds that his snug home with Gladys and Kate has been reduced to “cinders, burned so completely that its ashes had mixed in with a common layer all about and then had been tamped down by the snows and washed and dissolved by the thaw.” Yet there is beauty too: Before too long, as Grainier drives through the valley in a wagon “behind a wide, slow, sand-colored mare, clusters of orange butterflies exploded off the blackish purple piles of bear sign and winked and fluttered magically like leaves without trees.” At night Grainier contemplates his own solitude as he “watched the sky. The night was cloudless and the moon was white and burning, erasing the stars and making gray silhouettes of the mountains.”

Railroad worker housing along the Southern Pacific Railroad tracks in Sacramento County, CA. (Image courtesy of the Library of Congress)

Railroad worker housing along the Southern Pacific Railroad tracks in Sacramento County, CA. (Image courtesy of the Library of Congress)

A tool shed along the Idaho Northern Railroad in Gem County, ID. (Image courtesy of the Library of Congress)

A tool shed along the Idaho Northern Railroad in Gem County, ID. (Image courtesy of the Library of Congress)

This spring the Pulitzer Prize board rejected all three nominees put forth by the fiction jurors—David Foster Wallace’s The Pale King (a behemoth at fifty chapters and 500 pages), Karen Russell’s Swamplandia!, and Johnson’s Train Dreams. If the Pulitzer intends to reward “the great American novel” or even “a great American novel,” then it is not difficult to discern the rationale behind the board’s decision to bypass Train Dreams at least. Johnson has written a novella that is more literary than historical (and his novel, Tree of Smoke, did win the National Book Award). Even had he intended to reveal the fraught enterprise of modern “progress”—the human price it exacts, and the natural barriers to it—then Train Dreams is only a qualified success, for it lacks the substance of a larger early twentieth-century story. Missing here is any meaningful intertwining of technology, capitalism, community, and the exploitation of labor and the organized resistance of laborers to that exploitation. The evocations of Train Dreams are not exclusively American; we can imagine, and document, similar themes in the history of Canada or Australia, for example—the prejudice and anger of various ethnic groups toward each other; the hard living of single men toiling in the forests and on the railroads; the unforgiving nature of the seasons; and the predatory wiles of beasts which are, perhaps, not so different from humans after all. Still, the story is a great pleasure to read.