Preso en su lecho mi rio pasa, pero se acerca su libertad.

Sus aguas dulces ya son saladas; ya no eres rio, eres el mar.

A prisoner within its banks, my river rolls on, soon to find freedom.

Your sweet waters now have grown salty; you’re no river, now, you are the sea.

Charo Cofré

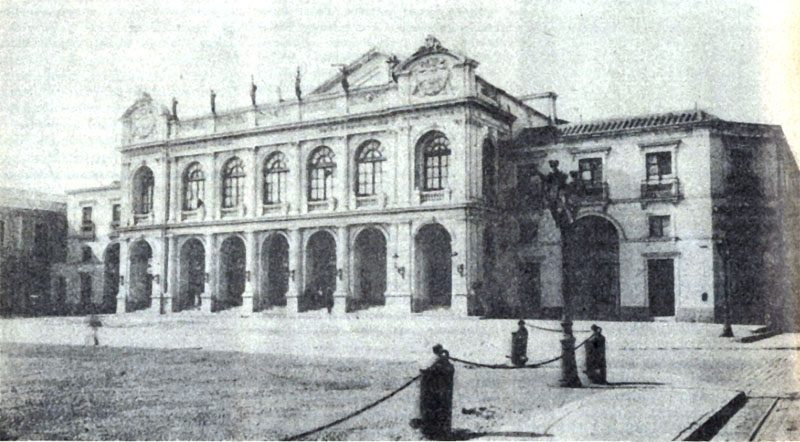

Colegio Andacollo was a K-through-12 parish school in old town Santiago. The Holy Cross Fathers took it as their new mission when the military government kicked them out of Saint George’s, their traditional academy for the elite. Andacollo was another world.

The original Andacollo was a mountain town in the north where Our Lady of Deep Rocky Mines granted solace and safety to her devoted followers. Our Andacollo was on the corner of Mapocho and Cautín, in a barrio of old multifamily dwellings, cheap bordellos, and the local seafood market. The place had a history of union struggle, fiery passion, and a profound commitment to the miracle-working Virgin of Andacollo. It also had a secret tale of tragedy.

Old town Santiago sat atop an ancient network of canals. Some were small but others were regular aqueducts, lined with stone and brick. Built for irrigation, they carried quantities of water from Canal San Carlos to the Mapocho River. Before there was pavement. When Matucana and Avenida Matta were still just vegetable gardens and chicken coops. Back when every home had tomatoes, basil, and cilantro growing out back.

The central region of Chile is still crisscrossed with canals that were built by a dozen Jesuit missionaries and several thousand local Indians. The intention was to strengthen the native communities against European invasion. Taking advantage of the melting snowpack in the mountains, they transformed a semi-arid wasteland into the now-famous fertile green valleys.

The effect on the indigenous population was the opposite of what had been intended. In 1550, the conquistadors said that Nueva Extramadura was too poor and not worth the trouble. By 1750, they had changed their conquering minds. Irrigated and green, the Spanish liked it. So, they threw out the Indians and the Jesuits, and they set up their haciendas.

One hundred and fifty-three “nice families” colonized with all the rapacious vigor of their prestigious lineages. They were Spaniards, Basques, and some French. They brought their cattle and their vineyards. They brought their illusions of noble breeding and Chile criollo was born.

Their descendants became the barrio alto, the GCU, as they say, Gente Como Uno, (People Like Us), a code that only legitimate members of their tightly-closed circle were supposed to recognize. It wasn’t about money, comrade, though the GCU did tend to be rich. It wasn’t about land, either, though they controlled most of it. The GCU sustained an Old World fantasy of hereditary aristocracy. They really believed it, and they insisted on marrying their children to each other. A rich man without a pedigree was called, roto con plata, more or less, a bum with lots of cash. If he had not descended from the legendary hundred families (who were, in reality, one hundred and fifty-three), he was and always would be an outsider.

The canals in the central valleys are still functional. They are the reason why there is Chilean wine and fruit at Whole Foods. Building a canal is no joke. It has to always go downhill so that the water flows forward and never backs up. In 1600, that was an engineering masterpiece.

As the population grew in old town Santiago, the canals lost their reason for being. Family gardens became parking lots and chicken coops became bus stops. They are mostly dry today, an underground labyrinth for which there is no known map. Only the rats know their way around.

But, until the late ‘60’s and early ‘70’s, the water continued to flow, and there was access at strategic places. Neighbors would draw a bucket or two to water a shade tree, or to dampen the streets and vacant lots in the summer. That kept the dust down as boys upheld an important tradition, the continuous game of pick-up soccer, la pichanga. No shirts, no shoes, no score, house rules. Everyone played until it was too dark to see your hand in front of your face. As the brown water flowed constantly down into the rocky Mapocho.

Flowing water was an urban temptation. Children learned early in life to toss all their trash into the open mouths of Santiago’s filthy underside. The subterranean monster swallowed everything, without complaining. What’s more, most homes still had no indoor plumbing. The canal was where people dumped their chamber pots. Anyone who drew a bucketful had to watch out for floaters from upstream. That was emblematic of the ongoing relationship between the barrio alto and los de abajo, the people down below. It just seemed natural that those in high places would dump their refuse on those who were geographically and socially below them. That was also the reason why typhoid and hepatitis were so common, down there.

There was an opening in the schoolyard at Andacollo. It was about two feet wide and three feet long, rimmed with discarded railroad ties. The canal water rushed by about a foot below the ground level. Like everywhere else, at Andacollo, the canal water was used to keep the dust down and get rid of the trash. There was a big willow tree in the middle of the schoolyard that provided shade on hot afternoons. The groundskeeper would make a trench around it with his trowel, and fill it with water from the canal, using his big iron bucket.

The school was all boys back then, and la pichanga never stopped. One day, the ball bounced close to the opening. As tradition demanded, the boy closest ran backwards with reckless abandon, to make the save. It’s a passion, comrade. When the ball was in play, nothing else mattered. He fell into the canal and disappeared.

The foul waters dragged him through their labyrinth. No rescue was possible; nothing anyone could do. They found him the next day in the Mapocho River. His clothes had been ripped off. His body was twisted and broken, but he was recognizable. He had been dragged through hell in an unexpected, surprising, and unavoidable way. I don’t know his name.

Back then, it never occurred to anyone to cover a hole in a schoolyard because someone might fall in. They told the boys to be careful. That was part of their education. They had to learn that any one of them could drop into the abyss at any moment.

That awful day, the dead boy’s classmates learned that destiny could betray you; that there were tragic, violent accidents; that the lives of poor boys didn’t really matter; that in five seconds, it could all be over and done with; that they, too, could disappear and be forgotten. That day, the boys learned that you have to be clever to survive in a cruel world.

Nowadays, we cover holes like that. We deceive our children with the illusion that the world is safe and trustworthy. That has never been true, but if you are under thirty, you were probably brought up to believe it and expect it.

The fickle nature of fate is the elephant in our proverbial living room. Everyone pretends it isn’t there. And the willow tree, silent witness to everything, grows tall.

The national anthem says that Chile is the copia feliz del Edén. That means a happy copy of paradise. But it’s just a copy, not the real thing. And Eden was a tricky place, comrade. You do remember what happened there?

You May Also Enjoy:

Civil War and Early Life: Snapshots of Early War in Guatemala by Vasken Markarian