by Tiana Wilson

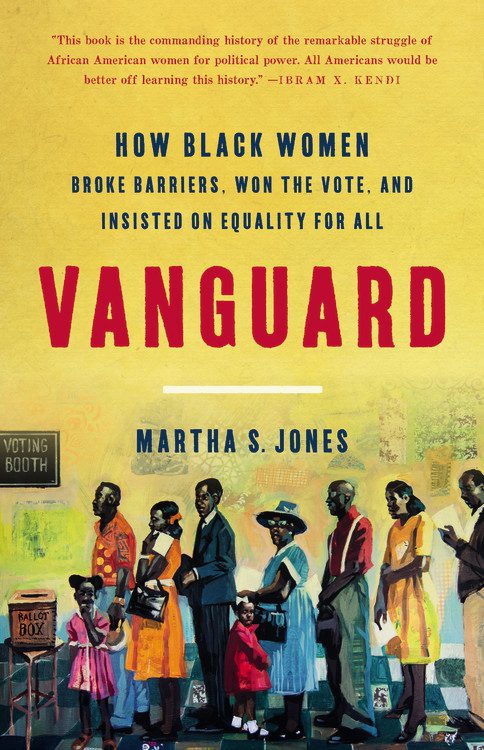

As we rapidly approach the 2020 US presidential election, Kamala Harris’ acceptance of the Democratic party’s nomination for Vice President offers great hope to a variety of marginalized communities who have been historically underrepresented in the national political arena. Harris, who identifies as a Black woman, is the daughter of Indian and Jamaican immigrants. Her initial presidential campaign and then her announcement as Vice President led different media outlets to portray her as the first Black woman and first candidate of Indian descent to be named on a major U.S. party’s ticket. Yet, this narrative is not complete and it obscures the great strides made by Black women that paved the way for Harris. Nearly five decades ago, in 1972, Congresswoman Shirley Chisholm became the first Black woman to seek a major party’s nomination for the US presidency. For anyone interested in contextualizing the current political climate, historian Martha S. Jones’ most recent work, Vanguard: How Black Women Broke Barriers, Won the Vote, and Insisted on Equality for All (2020), is a must read. She provides us with a sweeping narrative of how Black women struggled for political power and how this galvanized a broader movement for human rights.

Tracing over two hundred years of political work, Jones foregrounds the different modes and strategies Black women took to not only actively participate in democracy, but also to confront racism and sexism in society. She argues that referring to Black women as the “vanguard” has a double meaning. On the one hand, Black women were the nation’s original feminists and anti-racists, emerging from brutal encounters with enslavement, sexual violence, and economic exploitation. At the same time, Black women pointed the US toward its “best ideals…realizing the equality and dignity of all persons” (11). Drawing on newspapers, books, court transcripts, speeches, letters, and memoirs, Jones raises up the voices of Black women and shows how their dreams of liberation were very different from those put forward by white women. Although winning the right to vote was one goal, Black women never limited their efforts to a single issue. Instead, Black women worked to secure civil rights, prison reform, juvenile justice, and international human rights. As Vanguard demonstrates, examining the long political history of Black women shifts the periodization of the larger women’s rights movement, reminds us the important role race played in women’s political goals, and disrupts our ideas of where political activity occurs.

As we continue to celebrate the centennial of the Nineteenth Amendment, Jones reminds us that the fight for women’s suffrage did not begin with Seneca Falls in 1848 neither did it end in 1920. Instead, readers are provided with a comprehensive narrative of the different tactics Black women utilized to obtain civil rights not just for themselves, but for other groups as well.

The first three chapters of Vanguard explores Black women’s political activism from the American Revolution era to the end of the Civil War. Jones begins the narrative in the late 1780s, because she argues the American Revolution ushered in an antislavery movement in the US and therefore offered Black women the opportunity to participate in this new public culture. In these early chapters, Jones introduces us to women like Jarena Lee, Maria Stewart, and Sarah Mapps Douglass who moved freely in the urban North and used their writings to denounce slavery, call other women to participate in politics outside of the domestic sphere, and challenge Black male dominance in religious environments. During this era, antislavery societies, benevolent associations, and literary clubs became new forums where Black women publicly gathered to discuss abolitionism and women’s rights. In this section, we also learn that although Black women linked arms across the color line, they were not in attendance at the infamous 1848 Seneca Falls Convention. Jones claims this was largely due to Black women’s commitment to antiracism and obtaining civil rights as a unified movement with Black men. However, in these predominately Black spaces, which were often times church conferences, Black women demanded equal treatment alongside their male counterparts.

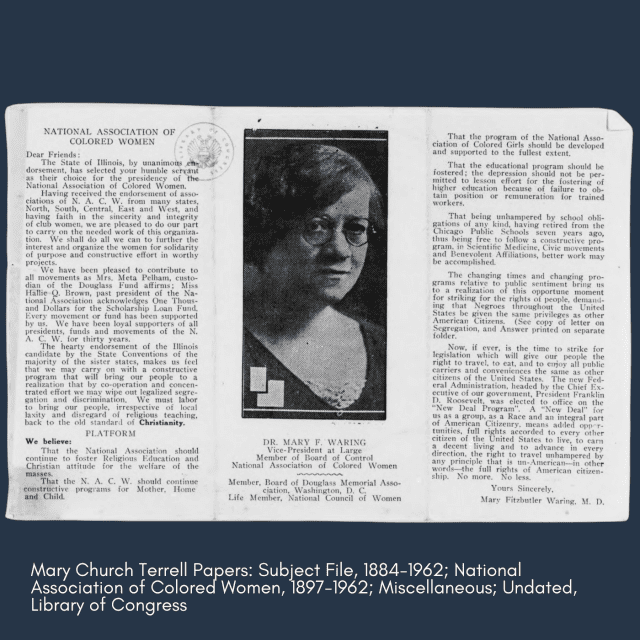

When the Civil War ended and Congress passed the Thirteenth Amendment, the nation underwent tremendous social, political, and economic changes. Although the fight for Black equality and women’s suffrage accelerated, Black women felt excluded from these larger conversations, which influenced them to establish their own organizations. The next three chapters of Vanguard discusses the emergence of a Black woman’s movement from the Reconstruction era to the end of the first World War. Black women chose not to join the two new national women’s suffrage organizations, the American Woman Suffrage Association and the National Woman Suffrage Association, because these groups were dominated by white women who upheld racism and suffrage alone was too narrow of an agenda for Black women. In these sections, Jones examines the leading Black women thinkers of this era, Black clubwomen and churchwomen, largely due to their ability to speak on civil rights and church politics in public arenas. For example, the National Association of Colored Women (NACW) coalesced under the motto “Lifting as we climb,” which implied that clubwomen were on the rise to racial progress, and they intended to help other Black women along the way (153). NACW’s first president Mary Church Terrell revealed the particular struggles of Black American women in 1904 when she traveled to Europe to give a speech at the World’s Conference of Women. As Jones points out, sometimes Black clubwomen held opposing ideas where some argued for women to have the right to be mothers and homemakers and others privileged suffrage.

The ratification of the Nineteenth Amendment in 1920 did little to change the everyday political realities for Black women. Jim Crow still dominated the South, and some Black women lost faith in obtaining voting rights and opted to put their efforts in Black Nationalist organizations like the United Negro Improvement Association (UNIA). Despite such discouragement, other Black women continued the fight and the last three chapters of Vanguard focuses on these women who worked tirelessly for the passage of the 1965 Voting Rights Act, which banned state and local governments from denying citizens equal voting rights based on race or color. The final section explores figures like Mary McLeod Bethune who worked with the Franklin D. Roosevelt administration, Fannie Lou Hamer who founded the Mississippi Freedom Democratic Party (MFDP), and Rosa Parks who was in attendance at Lyndon B. Johnson’s final details ceremony for the Voting Rights Act.

As we continue to celebrate the centennial of the Nineteenth Amendment, Jones reminds us that the fight for women’s suffrage did not begin with Seneca Falls in 1848 neither did it end in 1920. Instead, readers are provided with a comprehensive narrative of the different tactics Black women utilized to obtain civil rights not just for themselves, but for other groups as well. The strength of this book lies in Jones’ ability to capture Black women’s diverse ideas that were simultaneously moderate and radical. Black women were not and are not a homogeneous group, and the history of our political work further illustrates this point. Vanguard is the ideal text for an undergraduate course or graduate seminar that covers US History topics like African American History, Women’s Liberation Movement, and Public Policy. I highly recommend it.