Steven Spielberg’s latest historical drama chronicles the 16th President’s final months and the struggle for passage of the 13th Amendment by the House of Representatives in 1865. Lincoln’s enduring popularity in both scholarly and popular circles means that this film will be subjected to intense scrutiny and debate by historians, movie reviewers, and culture warriors.

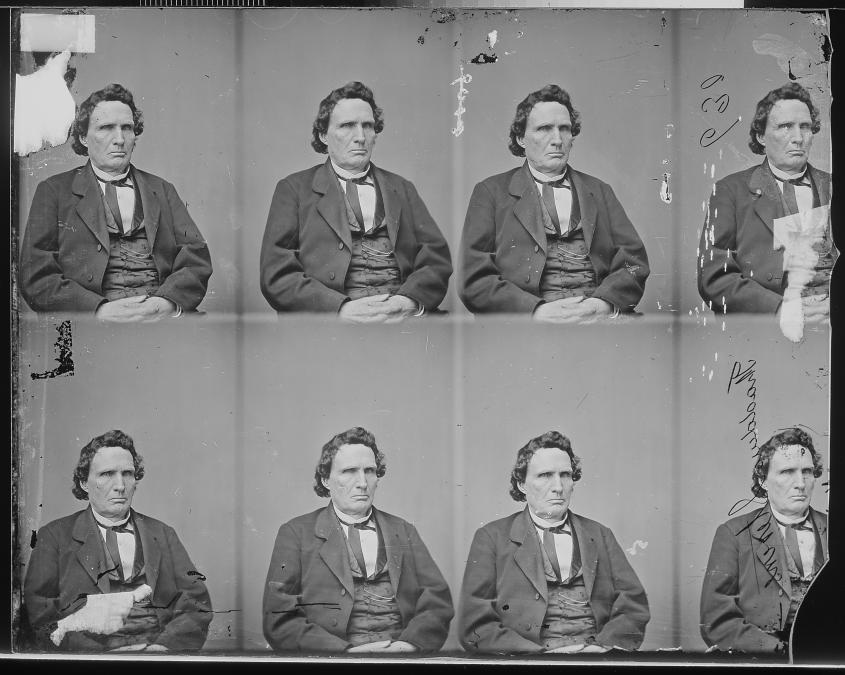

Fortunately, Lincoln is blessed with a remarkably accomplished cast. Daniel Day Lewis is Abraham Lincoln. Having supposedly read over 100 books on Lincoln in preparation for the role, he manages to convincingly replicate many aspects of Lincoln’s persona and physical aura. Lincoln’s purportedly high voice, his wry sense of humor and knack for storytelling, his slouched posture and awkward gait, and the overwhelming weariness incurred by the “fiery trial” of war all ring true in this portrayal. Mary Todd Lincoln (Sally Fields) is portrayed as a more or less sympathetic character, in accordance with more recent scholarship rejecting long-standing depictions of Mrs. Lincoln as a shrew, possibly suffering from a mental illness. Instead, Fields plays a First Lady who is grief stricken over the loss of her son Willie and weary from the stress of a wartime presidential marriage. During a scene at a White House reception, she draws on her social training as a daughter of the Kentucky planter elite to skillfully and acerbically defend herself and her husband against political critics. Secretary of State William H. Seward (David Strathairn) also appears as an important source of support for Lincoln. Seward cuts patronage deals with lame duck Democratic Congressmen in order to help secure the passage of the 13th Amendment and acts as a sort of political muse to Lincoln. Seward harangues and cajoles Lincoln on policy and political strategy but ultimately serves as a loyal ally in carrying out Lincoln’s intent, a depiction born out in the historical record. Thaddeus Stevens (Tommy Lee Jones) is also a convincing secondary character, albeit with some historical problems. A leader of the Radical wing of the Republican Party, Stevens is accurately portrayed as an advocate of racial equality and a vehement opponent of secessionists. However, a scene revealing the purported relationship between Stevens and his African-American housekeeper risks conveying the sense that this relationship was the primary motivation for Stevens’ crusade for the 13th, 14th, and 15th Amendments.

Despite the excellent performances turned in by the star-studded cast, Lincoln has a number of shortcomings from the historian’s point of view. Based on Doris Kearns-Goodwin’s Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham Lincoln, the film is at times a taut political thriller and at times the inspirational story of the final abolition of American slavery. The choice to focus on the last few months of Lincoln’s presidency is appropriate given the ultimate outcome of the American Civil War: the defeat of the

Confederacy and the end of legal slavery. However, this narrow focus glosses over Lincoln’s famously ambiguous views on slavery and racial equality. Spielberg’s Lincoln appears committed to rapidly ending slavery and even suggests that suffrage might be extended to black men in the future. In his lifetime, Lincoln was consistently criticized by Radical Republicans and African-American leaders such as Frederick Douglass for his equivocation on slavery and lenient plans for Reconstruction. Lincoln seems to have held a lifelong commitment to the free-soil ideology that every man, white or black, has the right to earn for himself by the sweat of his brow. Despite this conviction, Lincoln repeatedly stated that he wished to preserve the Union, either with or without slavery. Lincoln viewed the Emancipation Proclamation and the enlistment of black troops as a wartime expedient to preserve the Union.

To its credit, Lincoln does make some references to contradictory statements Lincoln made earlier in his presidency about slavery. Despite this nod toward the complexity of Lincoln’s political career, Spielberg risks reviving the Great Emancipator myth. The best evidence suggests that Abraham Lincoln personally abhorred slavery as an institution while simultaneously denying the concept of racial equality. Some historians have argued that Lincoln’s personal beliefs underwent a significant change during the last year of the Civil War, and Lincoln did in fact suggest to the reconstructed government of Louisiana in 1864 that “very intelligent” black men and “those who have fought gallantly in our ranks” might be given access to the ballot box. As depicted by the film, during the 1864 Presidential campaign Lincoln threw his support behind passage of the 13th Amendment and was active in securing its passage in 1865. Nonetheless Lincoln never became a radical abolitionist like Thaddeus Stevens or an outright advocate of racial equality. Lincoln continued to put forth plans for the resettlement of freedmen to the Caribbean even after issuing the Emancipation Proclamation and possibly even after the passage of the 13th Amendment.

Too narrow a focus on the actions of Lincoln and other white politicians unfortunately downplays the role played by both enslaved and free African-Americans in the Civil War-era struggle for freedom. Black characters largely appear passive in Spielberg’s account. Kate Masur points out that White House servants Elizabeth Keckley and William Slade were deeply involved in the free black activist community of Washington, D.C. Instead of appearing as dynamic characters within the President’s household, they are relegated to cardboard roles as domestics. Keckley has one brief, earnest discussion with Lincoln, but cannot offer a vision of black life outside of slavery to the President. Frederick Douglass, who visited the White House during the time depicted in the film, does not appear at all. The most assertive black character in the movie is a soldier who confronts the President about past ill-treatment and future aspirations. Lincoln artfully deflects the soldier’s concerns and the scene ends with the soldier quoting the Gettysburg Address. The one-dimensional black characters in Lincoln are unrecognizable as depictions of African Americans during the Civil War. Early in the war, when Lincoln strenuously wished to avoid confronting slavery, black enslaved workers fled to federal lines and congregated around federal camps such as Fortress Monroe, Virginia. Congress passed the Confiscation Act of 1861 in reaction to this development, marking the first movement by the federal government to separate rebellious slaveholders from their enslaved workers. While Lincoln continued to insist that the war was a struggle to preserve the Union, African Americans did not wait for the Emancipation Proclamation to turn the war into much more than a sectional conflict. Slavery was destroyed as much by their individual actions as by the political workings of white politicians.

A number of smaller inaccuracies and stylistic issues can be pointed out. For example, Alexander H. Coffroth is depicted as a nervous Pennsylvania Democrat pressured into voting for the 13th Amendment. Coffroth actually served as a pallbearer at Lincoln’s funeral, indicating that he was more than a simple political pawn of the White House. In another scene supposedly taking place after the fall of Richmond and Petersburg, Lincoln solemnly rides through a horrific battlefield heaped with hundreds of bodies. A battlefield such as this would likely represent one of the worst instances of combat in the Civil War. Richmond and Petersburg fell primarily due to General Ulysses S. Grant’s maneuvering to cut Confederate supply lines rather than through bloody fighting on the scale Spielberg depicts. Lincoln did in fact visit Richmond after it had fallen and was greeted there by hundreds of jubilant freed slaves in the streets of the former Confederate capital. The chance to depict such a poignant scene is not taken up by the filmmakers in favor of a continued focus on the political and military struggle waged by white Americans.Perhaps most inexplicably, the movie does a poor job of identifying the various cabinet officials and Congressmen central to the plot. While this poses little obstacle to historians familiar with the time period, the average moviegoer is likely to be somewhat unsure of the exact role or importance of several characters. This is especially curious given the fact that obscure members of a Confederate peace delegation such as Confederate Senator R.M.T. Hunter and Assistant Secretary of War John A. Campbell are explicitly identified on screen.

Taken on the whole, Spielberg’s Lincoln is a masterful politician and a dynamic character, able to carefully mediate between his own evolving beliefs and the political realities of his age. This interpretation falls solidly in line with the mainstream of Lincoln scholarship. For an incredibly complex, sphinxlike figure such as Abraham Lincoln, perhaps we shouldn’t expect a more thorough interpretation from Hollywood.

***

You may also like:

Henry Wiencek’s NEP review of Eric Foner’s The Fiery Trial, which examines Lincoln’s changing views on race and slavery

Photo Credits:

Series of Thaddeus Stevens photographs by Matthew Brady, sometime between 1860 and 1865 (Image courtesy of Brady National Photographic Art Gallery)

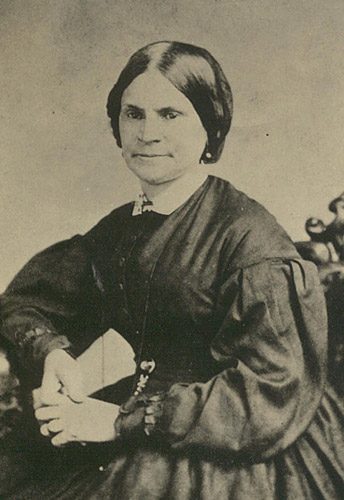

Lydia Hamilton Smith, housekeeper and alleged common law wife of Thaddeus Stevens, photographed sometime prior to 1868 (Image courtesy of Wikimedia Commons)

Mary Todd Lincoln, 1846-7 (Image courtesy of Library of Congress)

Lincoln depicted as The Great Emancipator in Thomas Ball’s statue, Lincoln Park, Washington, DC (Image courtesy of Library of Congress)

Promotional studio image of Abraham Lincoln (left) and Daniel Day-Lewis as Lincoln (right)

Images used under Fair Use Guidelines