By Katherine Leah Pace [1]

From the Editors: This article is accompanied by a comment from Edmund T. Gordon, Associate Professor of African and African Diaspora Studies & Vice Provost for Diversity at the University of Texas at Austin. Such comments are a new feature for Not Even Past designed to provide different ways to engage with important research.

Parks have long been implicated in the construction of racially inequitable urban spaces in the United States. Cities built and continue building more and better parks in white neighborhoods. Parks were and remain de facto or effectively segregated. In the Jim Crow South, cities used parks to segregate races, locating their only colored parks in officially designated Black districts. Today, parks are implicated in wider processes of gentrification and the displacement of communities of color.

Austin, Texas’ Waterloo Park speaks to another side of the historic relationship between parks and race in US cities. In the 19th century, as urbanization accelerated across the US, racial capitalism drove Black people and poor people of all backgrounds into hazardous and otherwise undesirable spaces, including industrialized spaces, steep land that was difficult to build on, and, most often, lowlands, where drainage pooled, and floods were common.[2] Poor and Black people set down roots in these inhospitable (but often generous) landscapes, establishing stable shantytowns and Black enclaves where they built homes and raised families.

As cities grew, they deployed parks to dislodge such communities, socially re-engineering hazardous urban space. They paid little attention to the social causes of poverty or the deep social and economic bonds that Black and poor communities developed. They provided displaced people with few or no resources for relocation. New York City’s Central Park, which displaced the Seneca Village and dislodged more than 1,000 shantytown dwellers from the rocky hills and swampy marshes of central Manhattan, is perhaps the most well-known example of such social landscaping.[3] Located in a riparian floodplain, Austin’s Waterloo Park is another example, although far less well known.

Flash Flood Alley

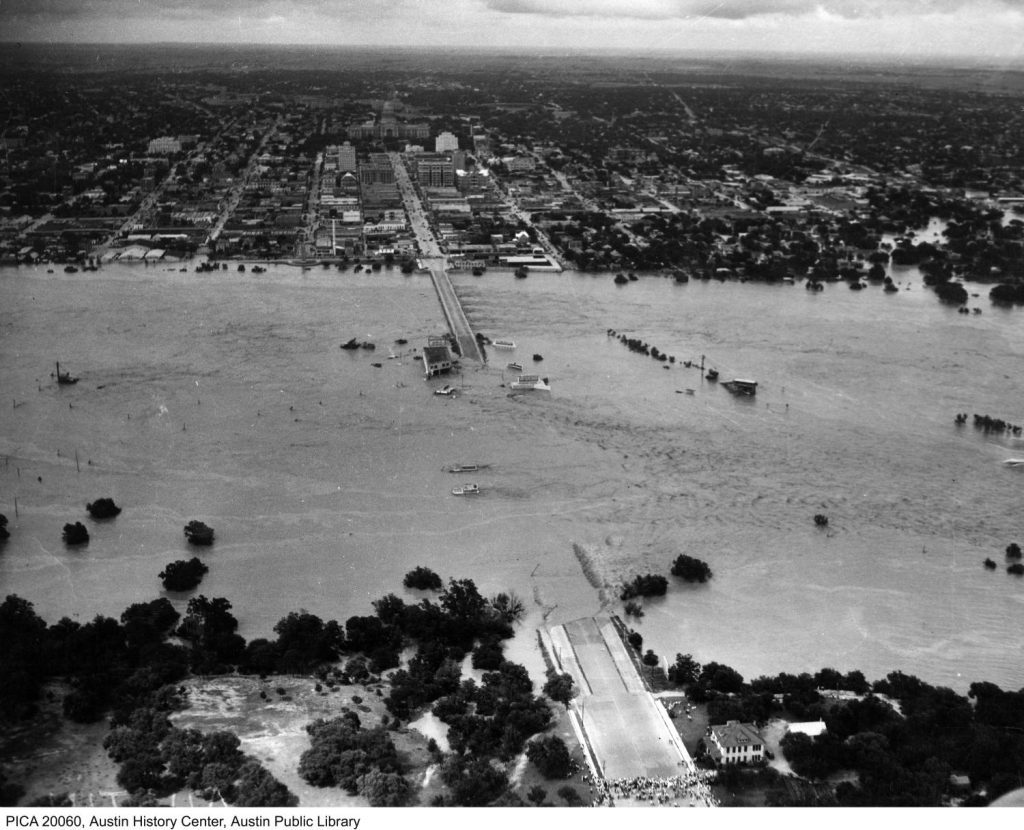

Austin is located in Central Texas’ “flash flood alley,” one of the most flood-prone parts of North America. Regional soils are often rocky or heavy in clay, and much of the terrain is steep, limiting the soil’s ability to absorb rainfall. The region is also a climactic convergence zone where warm maritime fronts moving inland off the Gulf of Mexico collide with cool northerlies and westerlies, rapidly condensing into intense storms. Thanks to the Balcones Escarpment, a range of cliffs and steep hills that arcs through Central Texas, such storms often stall, further intensifying rainfall over affected watersheds and triggering sudden, momentous, and enormously destructive flash floods.

When settlers poured into Central Texas in the 1870s, they brought with them farming, grazing, and logging practices that denuded the land, causing erosion. Soil acts as sponge and reservoir, absorbing rainfall and feeding streams between rain events. As it washed away, creeks began to run dry, and floods became more frequent and intense. Major river floods in Austin came to an end in 1938, when two of five Highland Dams along Texas’ Colorado River were completed. However, the city’s creeks continued flooding. As Austin grew, new development covered more and more land with impermeable surfaces, further reducing creek flows and exacerbating floods.

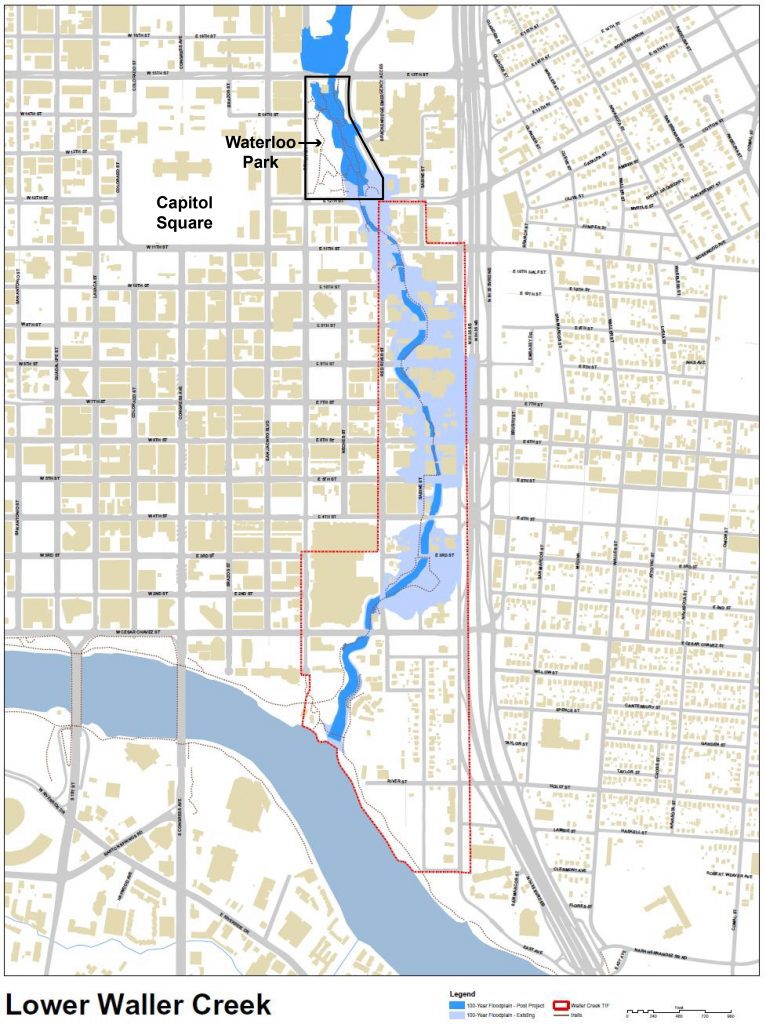

Waterloo Park

The largest green space in downtown Austin, Waterloo Park takes its name from the Waterloo hamlet, a frontier settlement that Austin replaced. It sits in a basin along Waller Creek, encompassing a particularly flood-prone stretch of Austin’s most central, urbanized stream. Though the park was built in 1975 as part of the Brackenridge Urban Renewal Project, its history dates to the end of the US Civil War, when formerly enslaved people began migrating to southern cities in search of work, education, lost family members, and haven from anti-Black violence. Many migrants were skilled farmers and craftsmen and had saved money to purchase land. As a rule, white landowners sold Black people only their “poorest” properties, relegating most Black communities to low-lying and otherwise hazardous spaces.

In the late 1860s, a cluster of flood-prone Black enclaves took shape along lower Waller Creek. Home to Black churches, schools, landowners, and businesses, the enclaves were internally segregated by topography, with their poorest residents living in shantytown communities along Waller Creek’s steep banks. Theses shantytowns passed through what is now Waterloo Park, occupying the area’s most flood-prone stretches. In the 20th century, city planners repeatedly turned to parks to dislodge Austin’s riparian “slums,” using Waterloo Park to displace a recalcitrant Black and brown shanty neighborhood located just east of the state capitol grounds. Given its location, it is easy to assume that the park was designed to mitigate flood hazards. In fact, it was designed to dislocate poor Black and brown people, mitigating “racial” hazards to nearby white property values.

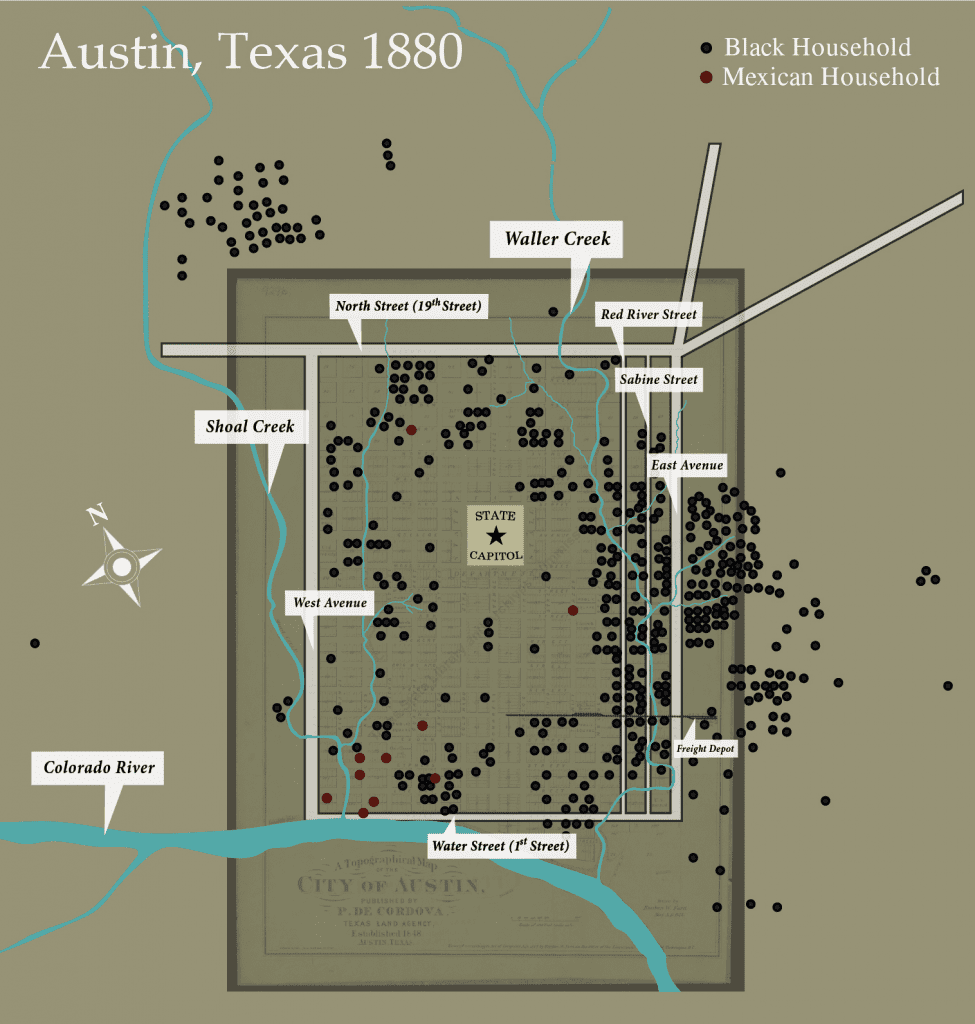

The Red River Community

A 1979 study by Austin’s Human Relations Commission contains maps of the locations of Black and Mexican residences in Austin in 1880. When superimposed atop a separate map that depicts the historic paths of central Austin streams, the commission’s data reveals the consistency with which 19th century racial capitalism drove Black and brown people into Austin’s riparian floodplains. It also shows that, in 1880, what is now Waterloo Park was home to a good dozen Black residences that formed part of a long, winding, Black residential cluster located along the lower, downtown stretch of Waller Creek, the epicenter of Black settlement in the city.

At the time, lower Waller Creek was home to three overlapping Black enclaves. Two residential enclaves, Pleasant and Robertson Hills, overlay two of the creek’s tributaries. A third downtown enclave followed the creek’s main branch. As this latter enclave had no formal name, historian Michelle Mears named it after Red River Street, a flat transit and commercial corridor along which Black businesses clustered.[4] In fact, the community was a riparian enclave, located by and large in Waller Creek’s floodplains.

Its beginnings date to July 1869, when a record flood swept down the Colorado River. Newspapers reported, the flood’s momentum “changed entirely” the “banks of the river” and washed away “two little islands.” The river’s tributaries backed up, and they too flooded. The following month, a white man sold an undeveloped lot at Red River and East 11th Streets to a Black man, Edward Aldridge, who subsequently sold a division of his lot to another African American. Soon after, another white man sold a lot at Red River and East 12th Streets to Vince McCraven, a Black man from Mississippi, who likewise subdivided his land and sold to Black buyers. Waller Creek “meandered” through the properties.[5]

By the time work on Austin’s 1872 city directory began, the main branch of lower Waller Creek was home to an established Black residential and commercial community. One block west of Red River Street, there was the Colored Methodist Church, and along the creek’s downtown stretch there were dozens of Black residences and businesses, almost all located squarely within Waller Creek’s floodplains. Jeremiah Hamilton, a Black carpenter from Bastrop, Texas and a member of the 12th Texas legislature, lived with his family at Red River and East 11th Streets, in a two-story triangular stone house they built. Out of the bottom story, they ran a grocery. Half a block down Red River Street there was another Black grocery and, next door, a Black shoemaker. One block east, on flood-prone Sabine Street, there was a Black poultry and vegetable peddler. The district was also home to four blacksmith workshops where nearly a dozen African American blacksmiths were employed. The enclave’s residents quickly founded the community-funded Evan’s Community School. In 1876, the school had 150 pupils.

Austin’s First Railroad

Completed on Christmas Day 1871, the first railroad to Austin connected the city to the Gulf of Mexico, briefly turning Austin into a regional trading hub and destination. Between 1870 and 1880, the city’s population more than doubled, and a bustling, working-class, east end district quickly sprang up around the Red River community. Criss crossed by new streetcar lines, the district was home to Black as well as white and immigrant residents and businesses, including a Lebanese grocery and white shoemakers, hotels, wagon yards, warehouses, and land agents. While a few Black and white merchants built large stone houses along or just off Red River Street, most of the district’s residents were working-class or working poor. Employed as day laborers, saloon keepers, grocers, seamstresses, laundresses, and the like, they lived in brick tenements or small frame houses. White residents were less likely to live and work in floodplains than their Black neighbors, but occasionally, poor white and Black families lived side by side, in the same flood-prone tenements.

First settled in the early 1870s by a mix of working-class Black and white families, what is now Waterloo Park was a residential neighborhood, part of both the east end district and the Red River community. An archaeological study of the area determined, “The white families who lived on these blocks tended to own their homes and live in larger houses located on the lots situated farther from the creek.” The study also determined, “The properties located closest to the creek were exclusively occupied by tenants and these tenants were primarily Black.” Mostly owned by absentee landlords, these flood-prone creekside properties were crowded with tiny shacks.

A Social Survey of Austin

In the early 20th century, typhoid fever was endemic in US cities. Spread by water contaminated with fecal matter, the disease plagued Austin’s crowded Black and brown neighborhoods, going largely ignored by city officials until the summer of 1912, when an outbreak sickened residents of Hyde Park, a white suburb. In response, the city closed dozens of wells and commissioned its Special Health Inspector, William B. Hamilton, to conduct a study of Austin’s sanitation hazards.

Hamilton’s 1913 Social Survey of Austin is shot through with racial prejudice. It nonetheless provides a map of Austin’s riparian shanty districts and, if read against the grain, a description through which the daily habits and humanity of Austin’s poor residents can be observed. The survey also reveals how one early city planner sought to use parks to racially landscape low-lying urban space.

According to Hamilton, Austin in 1913 was one big sanitation hazard. Stables and slaughterhouses drained into nearby streams. Alleyways were clogged with garbage. However, the most offensive parts of the city were located along “Waller Creek and the two draws which run into it” and in “the three blocks near the mouth of Shoal Creek,” which flanks the west side of downtown. These densely populated areas had neither water nor sewage lines. Hamilton wrote, Waller Creek was “an open sewer from Nineteenth Street to the river.” Small shacks were “jammed together” on both sides on the waterway, along with wells and outhouses, many of which dropped “compost…directly into the creek.” Houses were overcrowded, unventilated, and poorly maintained, yet landlords charged inflated rents. In the 1870s, Mexican people began settling around Shoal Creek’s flood-prone convergence with the Colorado River. Hamilton wrote that this area “in no way differ[ed] from Waller Creek,” except that it was home to Austin’s main garbage dump, located on the riverbank.

Hamilton observed poor but hardworking people carving livelihoods from the urban landscape: fruit peddlers along lower Waller Creek, Black and white people fishing “any time of the day” in the river, the laundry of well-to-do families hung over Shoal Creek to dry. He focused his attentions elsewhere: on the unsanitary living conditions in Austin’s shantytowns, on a widely held belief that such conditions created anti-social individuals, and on what he saw as a threat to Austin’s development. He wrote,

Austin is paying a heavy price because of her bad housing conditions She has received much damaging advertising by permitting these conditions to exist…This city should and will become the Mecca for cultured people . . . where men, having made a success in business in smaller towns, are wont to make their residence. The best advertising the Austin Chamber of Commerce can do is to see that the housing conditions are improved at once.

Toward this end, Hamilton insisted the city tear down its shacks and institute new building codes. He blamed unscrupulous landlords for Austin’s shantytowns and suggested that, if the city razed its riparian floodplains but left the land open to private development, such landlords would inevitably erect new shacks along the city’s streams. To resolve this dilemma, Hamilton proposed the city use zoning and parks to socially landscape its floodplains. The three blocks around the mouth of Shoal Creek would become a manufacturing district. About Waller Creek, Hamilton wrote, “The bed of the creek divides the blocks into two parts, neither of which is deep enough for a residence lot. We may expect nothing but shacks to be erected here.” He concluded, “The shacks along Waller Creek should be moved back or torn down for one block on each side, the creek cleaned out…and parked from Twenty-seventh Street to the river.” This was “the only solution of the housing question along its banks.”

Hamilton’s vision developed in tangent with local park movement. In 1909, shortly after beginning his first term as Austin’s mayor, Alexander Wooldridge began developing Austin’s rudimentary park system. The city cleaned up a downtown park, curbed new parks along the east edge of downtown, and began planning a river park. Attune to these developments and to park planning trends, Hamilton proposed that parks along Waller Creek “connect with the river front park the city is planning and give a continuous chain of parks and drives.”

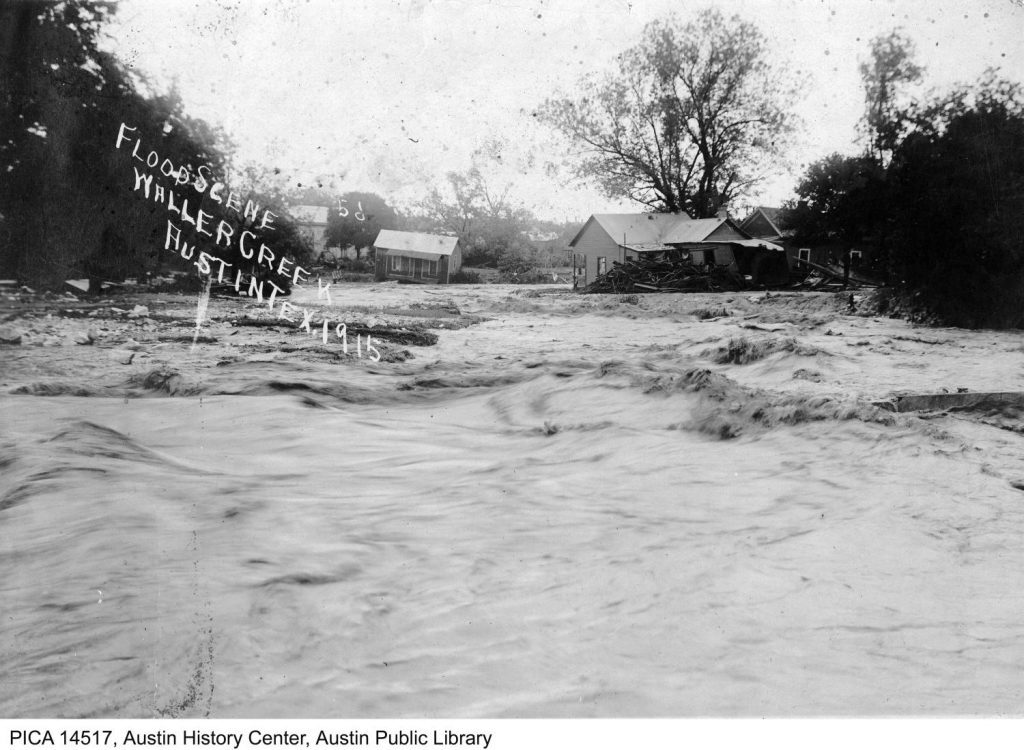

1915 Flood

On the night of April 22, 1915, numerous storm systems stalled over Austin, triggering deadly flash floods. The local newspaper reported the following day, “Without any warning the floods came, the waters in Shoal and Waller Creeks coming in a surging mass before the people living along the banks had any inkling that death lurked near.” Flooding was most severe along Waller Creek. Federal engineers later wrote, a “cloudburst at its [Waller Creek’s] head contributed so much water in such a short time that the stream . . . tore out all bridges, retaining walls, and adjacent buildings.”[6] According to the Austin Statesman, “Nearly every house on the banks of Waller creek was either flooded or moved by the water…The Mexican and negro population on the east side suffered heavily from the loss of life and property.”

A small capitol and college town, Austin struggled with the cost of rebuilding essential urban infrastructure, forcing the city to put most of its park plans on hold. Contrary to Hamilton’s visions, Austin’s riparian shantytowns remained intact. Early 20th century sanitation surveys nonetheless laid a foundation for future, comprehensive city plans, and indeed, 15 years later, Hamilton’s ideas would reappear in modified form in Austin’s first master plan.

A City Plan for Austin

Approved in 1928, Austin’s first master plan was written by a Dallas-based planning firm, Koch and Fowler. Infamous for institutionalizing residential segregation and racist zoning policies, it joined a national wave of first master plans produced by graduates of newly established university planning programs. Geographer Samuel Stein explains that comprehensive city planners “imagined themselves to be efficient, scientific, apolitical experts.”[7] In reality, the planning profession embraced segregation. Across the South, planners collaborated with cities to codify residential segregation, first using racial zoning (ruled unconstitutional in 1917) then directing cities to set aside tracts of land for “negro villages” where colored public facilities, including parks and schools, would be strategically located.

Austin officials likewise tasked planners with solving the city’s “race segregation problem.” Koch and Fowler noted that, while Black people lived around Austin, the area just east of downtown was “all black.” As so happens, this area was home to one of Waller Creek’s riparian enclaves: the city’s largest Black enclave, Robertson Hill. Planners recommended the city turn this area into “a negro district.” They also suggested the city concentrate industry in East Austin, establishing zoning policies that would disproportionately expose Black and brown residents to noise and pollution.

Less well-known are Koch and Fowler’s attempts to use parks to racially engineer low-lying urban space. For one, parks would protect unpopulated lowlands from inferior development. Planners wrote about a “low lying property” in North Austin, “It is in the midst of a high class resident area and if developed for residential purposes would naturally be used for a cheap inferior type of residences…the entire area should be converted into a large neighborhood park.” For another, parks would displace inconveniently located Black enclaves. Clarksville, a Black bottomland community located in West Austin, was “occupied by the cheapest type of negro shacks whereas the property immediately adjoining is more valuable.” Koch and Fowler recommended the “establishment of a neighborhood park” in the area, explaining, “The acquisition of this property for park purposes, and the removal of the present type of development, will increase the value of the surrounding property.”

To manage development along Shoal and Waller Creeks, Koch and Fowler recommended the city build modern parkways, that is, wide, paved, naturalistically landscaped roads with regulated traffic flows at intersections, limited points of access, improved lines of sight, and cut offs leading to parks. When explaining their parkway design, Koch and Fowler did not mention floods. Rather, they wrote,

The recommended boulevards and parkways would serve, first and foremost, as a trafficway…The fact that some of them border creeks and ravines, does not necessarily mean that they were located primarily on account of the natural scenery, but rather on account of the natural grades available and the fact that such ground is usually more unsuited for residential purposes.

Planners elaborated, writing that undeveloped land along Shoal Creek

“is flanked on either side by high bluffs, and very desirable residential property. Between the bluffs…are considerable lowlands which are not particularly desirable for residential use. We are recommending that the lowlands of this valley be acquired for a large park…to control the nature of developments of the bluff front properties.”

About the Waller Creek Parkway, planners explained,

“The completion of this drive will entail the acquisition of certain cheap property along the banks of Waller Creek from Eighth Street to Nineteenth Street. Most of the property which will be needed is at present occupied by very unsightly and unsanitary shacks inhabited by negroes. With these buildings removed . . . remaining property will be of a substantial and more desirable type.”

In the words of its planners, Austin’s first proposed comprehensive park system was not designed to take advantage of natural scenery, let alone mitigate floods hazards. It was designed to racially engineer low-lying urban space, to rupture the relationship between topographic and racial gradients, eliminating perceived racial hazards to nearby white property.

Jim Crow

Faced with budgetary constrictions, the city limited its park plans, opting to acquire only undeveloped lowlands in North and West Austin, where it built a scaled-down version of the Shoal Creek Parkway. It straightened a bend in Waller Creek at 3rd Street, the site of white Palm Elementary School. Next to the school it built Palm Park, displacing shanties from the area. Throughout the Jim Crow era, these were the only major developments along lower Waller Creek, and the Red River community, including most of its riparian shantytowns, remained in place.

Black businesses – amongst them a funeral home, a print shop, at least two car garages, and multiple antique stores – remained clustered in the east end district’s flood-prone stretches. The first of these antique stores opened in 1918 at Red River and East 8th Streets and was run by Simon Sidle, a horse trader from Pflugerville, Texas. Sidle taught his daughter Theresa the tricks of the trade, and in the mid-1940s, she and her husband Tannie opened an antiques store at Red River and East 12th. They were soon joined by other secondhand dealers, Black and white. As the 20th century advanced, the east end became increasingly commercial, but what is now Waterloo Park remained a mixed-race residential neighborhood.

Austin’s Mexican population grew rapidly in the 1920s, after the federal government waived immigration restrictions on contracted Mexican workers, triggering mass migration from Mexico to the US. Growing numbers of Mexicans settled along lower Waller Creek, opening meat markets, restaurants, and other businesses. They also moved into Waller Creek’s flood-prone brick tenements, and they crowded into the creek’s shantytowns, in some stretches quickly becoming the majority. In the late 1940s, Paul Sessums, a white a teenager, shined shoes downtown, along East 6th Street. He recalled in a 1996 interview, “Waller Creek was all Mexican laborers in little houses…There wasn’t stabilized land like there is now. A lot of it sloped down, and you had floodings…all the Mexicans lived down there where it flooded all the time.”

The Shanties in Waterloo Park

Just east of the capitol grounds, in a particularly flood-prone basin along lower Waller Creek, there was a shanty neighborhood about which politicians and the media repeatedly grumbled. In 1937, national Congressman Lyndon B. Johnson visited the capitol. He later lamented in a radio address,

“On Christmas . . . I took a walk here in Austin – a short walk, just a few blocks from Congress Avenue, and there I found people living in such squalor that Christmas Day was to them just one more day of filth and misery. Forty families on one lot, using one water faucet. Living in barren one-room huts . . . . The need for clearing our slum areas is apparent.”[8]

Scholars assume Johnson walked a few blocks east, where he came upon Waller Creek.

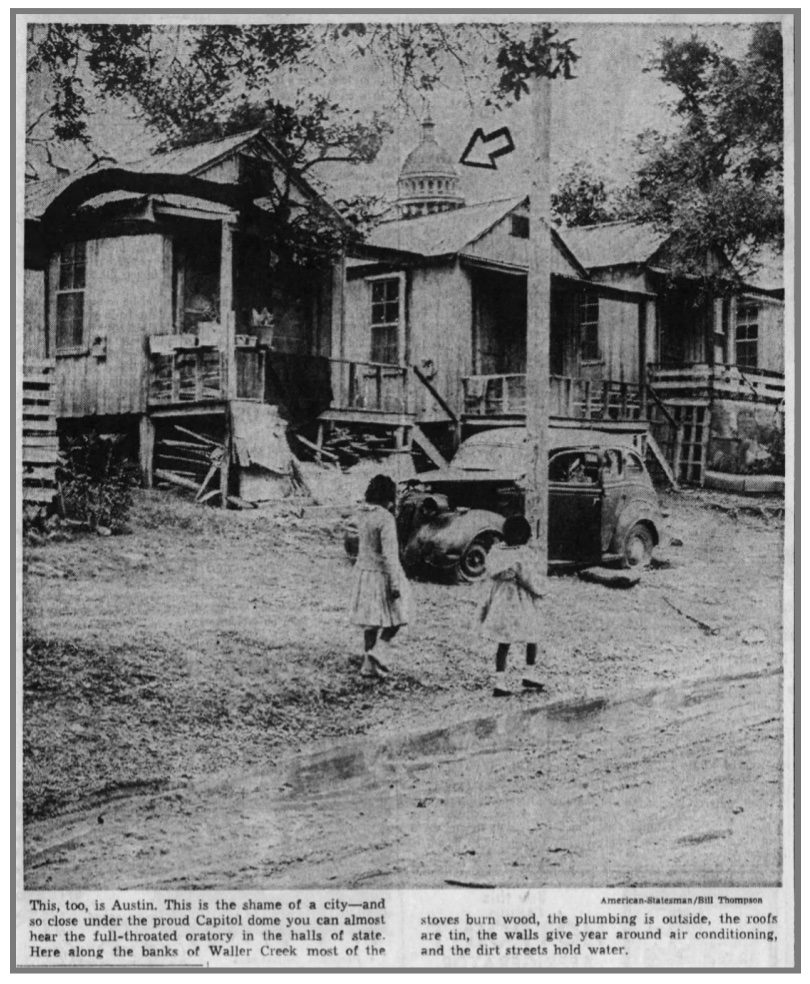

In 1955, the Texas Observer reported on the “hideous melange of shacks, privies, and abandoned frame houses” in Austin’s slum districts. While the most concentrated slums were in East Austin, the reporter wrote, “Within a two-minute walk of the spreading lawns of the Capitol grounds, eight people live in three rooms with wood for heat and no glass in the windows. On up the same street, a Mexican mother keeps her four children in two rooms with wide cracks between the floorboards.”

In 1961, the Austin Statesman published another tirade directed at Austin’s slums. The article began with a description of an elderly, shawled woman chopping wood along Waller Creek, “in a tilting shack little larger than a telephone booth…Down the hill behind the house, a blown-out tire rotted in the shallow creek . . . . Over the wood chopper’s shoulder, the Texas State Capitol dome looks like next door.” The article’s lead photograph is a rare image of Waterloo Park’s historic shanty neighborhood. In it are two neatly dressed Black girls walking side by side. Beyond them is a row of rickety frame houses, and beyond the houses the capitol dome. To draw attention to the capitol’s proximity, the photo was edited. A tree was removed and replaced with a cut-out of the dome, and an arrow pointing to the dome added.

In 1965, the Statesman reported on a school bus tour of proposed urban renewal sites. The article was accompanied by a photo of two white schoolgirls peering at a ramshackle wooden building. Again, the capitol dome rises above the tree line. The following month, Austin’s urban renewal agency submitted its Brackenridge Urban Renewal Project plan to federal agencies for approval.

Brackenridge Urban Renewal Project

By the 1940s, real estate and commercial capital was leaving US cities, following America’s white middle-class to spacious, segregated automobile suburbs. Increasingly, deteriorating downtown buildings and parks sat empty. Racist lending practices denied communities of color loans with which to repair their homes, further contributing to the deterioration of inner-city building stock. In response, developers and city officials lobbied the federal government to facilitate new building by razing the country’s slums, a process referred to as “urban renewal.” To gain judicial approval for massive clearance projects, urban renewal supporters latched onto the concept of economic blight, according to which slum conditions were a contagious public hazard.

The Housing Act of 1949 authorized the federal government to subsidize the cost of purchasing and razing blighted areas, which would then be sold to private developers. Thanks to the work of housing reformers, the act also authorized public housing construction, but lawmakers appropriated minimal tax dollars toward such ends. Instead, urban renewal rapidly morphed into “a quest . . . to maintain the downtown area as the dynamic center of the city.”[9] The vague concept of blight enabled urban renewal agencies to target stable neighborhoods that were “profitably attractive” to developers. It also enabled such agencies to target Black communities, preventing school integration in the wake of the Supreme Court’s 1954 Brown v. Board of Education ruling, and making downtowns more attractive to white people.[10]

Approved in 1968, the 144-acre Brackenridge Urban Renewal Project stretched from East 10th to 19th Streets and from the Capitol Square east to Interstate Highway 35, encompassing the northern half of downtown Austin’s east end district and the Red River community. According to project documents, it was designed to give the University of Texas, Capitol Square, and city Brackenridge Hospital room to grow and to enhance the area’s “environmental characteristics,” spurring new development.

At the time, the east end was one of downtown Austin’s liveliest districts, home to inexpensive housing and hundreds of businesses. Red River Street had developed into a popular secondhand strip, lined with “we buy and sell anything” shops and fine antique dealers.[11] According to Austin’s 1971 Black Business Registry, seven of these secondhand stores were Black run, amongst them Tannie and Theresa’s Antiques, which in the 1950s had moved to a larger building at Red River and East 11th Streets. The business registry also listed two black car mechanics on the same flood-prone stretch of East 7th Street as the Fowler Electric Company, a Black appliance repair shop. At the flood-prone intersection of Sabine and East 15th Streets, there was a Black drug store.

In 1972, all the buildings in the Brackenridge Urban Renewal Project area were razed, dislodging Black people from their century-long hold on lower Waller Creek’s floodplains and, in the process, displacing nearly 150 businesses and over 200 families. Just east of the capitol grounds, along that particularly flood-prone stretch of Waller Creek, Austin’s urban renewal agency built Waterloo Park. Project documents explained,

To enhance the project areas as a “front-door” to the City of Austin and the State Capitol grounds, a public parkway along Waller Creek is proposed . . . which will in turn enhance the economic value of those private redevelopment parcels adjacent thereto. This space will also serve as a drainage area since most of this proposed dedicated parking is subject to flooding by Waller Creek on a 50-year frequency.[12]

Brackenridge project documents made no mention of shacks along Waller Creek, speaking instead in general terms about overcrowded buildings and undesirable mixed uses. Urban renewal planners nonetheless did with Waterloo Park precisely what their predecessors recommended. To boost nearby property values, they built a park in Waller Creek’s floodplains, displacing Black and brown shanties. Notably, project documents referenced floods only once and briefly.

Most residents displaced by the Brackenridge project had few places to go besides already crowded slums in East Austin. As renters, they received little compensation, and Austin built little public housing. While the project did not immediately displace Black businesses south of 10th Street, a 1983 Black business registry lists only two black businesses in the east end. In a 2005 interview, Theresa’s niece, Dorothy McPhaul, said about the Brackenridge Project, “they killed a part of history when they did away with Red River,” taking “all that property for a park where hardly no one goes to.”[13]

A Homeless Refuge

Contrary to planners’ expectations, the Brackenridge project did not stimulate new development. In the mid 1970s, in order to receive federally subsidized flood insurance, Austin passed two floodplain ordinances, one preventing development in 100-year floodplains if such development would raise flood levels by more than one foot, and another prohibiting development in 25-year floodplains altogether. As a 1975 Waller Creek Master Plan explained, because of these regulations, “creek development is more expensive than similar development elsewhere.” Such regulations deterred would be developers of lower Waller Creek. Its business strip disrupted by urban renewal, the once bustling east end district languished.[14]

In 1977, the city began construction on a Waller Creek greenbelt running from Waterloo Park to the river. While greenbelt advocates predicted the new recreational amenity would spark nearby investment, greenbelt planners and designers quickly realized that, without flood control measures, floodwaters would wash their work away. Bickering between greenbelt planners and the city quickly ensued, and just as quickly, funds for the project ran short. In early 1982, soon after Austin’s 1981 Memorial Day flood, residents acquired a flood-damaged, incomplete, and at places inaccessible Waller Creek trail. The city promised additional improvements, but as one reporter concluded, “investors won’t be willing to commit capital in development along the creek unless they are sure that the creek won’t rise and ruin them.” The city knew this too, and it washed its hands of the waterway.

Austin’s most central waterway, Waller Creek was by this point the city’s most urbanized and polluted stream. It smelled. Thick algae grew at its edges. Its occasional current spewed grey foam. Aesthetically unpleasant and physically daunting, Waller Creek’s new greenbelt attracted few visitors. While Waterloo Park hosted occasional concerts and festivals, it was surrounded by office buildings whose workers used the park not at all or only briefly during lunch hours or breaks. As such, most days, the park likewise sat empty.

In the early 1980s, as homelessness surged nationwide, unhoused people occupied Austin’s relatively private green spaces, establishing permanent campgrounds in downtown parks, near downtown social service providers. In 1985, after a protracted site search, Austin decided to build a new, larger homeless shelter at Red River and East 7th Streets, in its blighted east end district, turning the area into the city’s homeless epicenter. Facing escalating public complaints about unhoused people, and worried that the sight of homelessness would hinder efforts to gentrify their downtowns, US cities began passing ordinances that criminalized homelessness – including public sleeping – empowering law enforcement to expel unhoused people from “prime” spaces where capital had been newly invested. The ordinances did not reduce homelessness, so police surrendered marginal spaces to people living on the streets. Austin followed suit, passing its first homeless ordinances in the 1990s.

Flood-prone and home to Austin’s largest homeless shelter, the east end remained an economically marginal district throughout the 1990s and early 2000s, even as other parts of downtown Austin rapidly gentrified. Unsurprisingly, police did not enforce the city’s homeless ordinances along lower Waller Creek. The waterway’s greenbelt became a homeless corridor, and Waterloo Park became one of the few places where people experiencing homelessness could sleep without worrying about being ticketed or forced to move.

The Waller Creek Tunnel

In the 1990s, thanks to a decades-long collaboration between developers and local and state officials, Austin transitioned from a capitol and college town into a sprawling Technopolis. Flush with new tax dollars, the city revisited the east end, deciding late-decade to build a mile-long flood diversion tunnel beneath lower Waller Creek. When construction began in 2011, the city closed most of Waterloo Park to begin work on a tunnel inlet, displacing the park’s homeless encampments.

Upon its completion in 2017, the tunnel opened 28 acres of downtown real estate to new development. Designed to reduce floods and to clean diverted water and pump it upstream, the tunnel promised to improve Waller Creek’s water quality. It also stabilized the creek’s banks, allowing construction to begin on the Waterloo Greenway, an updated park and trail system along lower Waller Creek.

The first of the greenway’s parks to be renovated, Waterloo Park reopened to the public in August 2021. An attractive space, the park is thoughtfully designed, with wide, paved paths that accommodate wheelchairs, bikers, and walkers. Narrower stone paths wind down hills planted with native shrubs, grasses, and trees. At the edge of the creek, there are native wetlands, and higher up, there are picnic areas, cleverly integrated children’s playscapes, and an amphitheater.

Notably, there are no groves, no tall dense plantings where people experiencing homelessness can shelter. Using landscape design, planners ensured that unhoused people would not reoccupy Waterloo Park. In this way, the park remains a tool with which to socially engineer low-lying urban space.

Comment by Edmund T. Gordon, Associate Professor of African and African Diaspora Studies & Vice Provost for Diversity

The country is in the midst of a reckoning in which the contemporary relevance of our collective racial past is being hotly contested. There are some who would legislate against learning about that past as a process too painful and divisive as well as irrelevant to our future as national and local communities. This piece by Katherine Pace, which makes a significant contribution to the racial history Austin, provides an important argument to the contrary.

Using Austin’s Waterloo Park and the social history of the post-bellum Waller Creek riparian flood plain, Pace demonstrates the raced and classed impacts of the City’s environmental and economic development policies. She clearly demonstrates how the economic logics of racial capitalism concentrated Black populations in the most environmentally unhealthy and perilous areas of the City – in this case the Waller Creek lowlands. She then shows how, as the surrounding real-estate becomes more valuable, Black and later homeless populations were displaced by roads and environmentally correct parks.

Pace’s work is an important example of the value of research and teaching in relation to our collective past. In recent years there has been much hand wringing about the increasing gentrification of Austin as the city has transformed into a Technopolis. This process is often characterized as a consequence of the economic development of the region and inevitability of associated market forces. Pace’s work shows us that economic interests and the city policy directed by those interests have long been an important factor in such processes in Austin.

More importantly, Pace’s piece shows us that such policy has a central racial component and that the reprehensible racialized outcomes have historically been cloaked in the seemingly benign garb of environmental protection and recreation. This is an extremely important lesson for liberal Austin, where environmental politics have played a key role in the City’s recent development. The work shows that like most other things in our nation and city, environmental concerns are not immune from the racial forces that plague our society. Knowledge gained and lessons learned from work like Pace presents here is essential to the forging of a more equitable future

Notes

[1] Much of the material in this history is taken from Katherine Leah Pace, “Forgetting Waller Creek: An Environmental History of Race, Parks, and Planning in Downtown Austin, Texas,” Journal of Southern History 87.4 (2021): 603–44. DOI: 10.1353/soh.2021.0124

[2] Coined by Black political scientist Cedric Robinson, the term “racial capitalism” highlights the ways that capitalism works through race, using racial differentiation and the devaluation of non-white lives to create an underclass of particularly exploitable workers of color and to socially differentiate space, raising the land values of white-only neighborhoods. Cedric J. Robinson, (1983; 3rd ed., Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2020).

[3] Lisa Goff, Shantytown, USA: Forgotten Landscapes of the Working Poor (Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, 2016).

[4] Michelle M. Mears, And Grace Will Lead Me Home: African American Freedmen Communities of Austin, Texas, 1865–1928 (Lubbock: Texas Tech University Press, 2009).

[5] Angela Parmelee, “Docent Training: Brief History of the Site of Symphony Square,” 1976, Folder 3, Box 2, Peggy Brown Papers, AR.2009.051, Austin History Center (AHC).

[6] House Documents, 66 Cong., 1 Sess., No. 304: Report on the Preliminary Examination of the Colorado River, Tex., . . . for Flood Protection (Serial 7643; Washington, D.C., 1919), 32.

[7] Samuel Stein, Capital City: Gentrification and the Real Estate State (New York: Verso, 2019), 25.

[8] “Tarnish on the Violet Crown: Radio Address by Hon. Lyndon B. Johnson, of Texas, on January 23, 1938,” Congressional Record, 75 Cong., 3 Sess., February 3, 1938.

[9] Robert B. Fairbanks, The War on Slums in the Southwest: Public Housing and Slum Clearance in Texas, Arizona, and New Mexico, 1935–1965 (Philadelphia: Temple University Press, 2014), 2.

[10] Wendell E. Pritchett, “The ‘Public Menace’ of Blight: Urban Renewal and the Private Uses of Eminent Domain,” Yale Law and Policy Review 21 (Winter 2003), 1–52.

[11] Gretchen Neff, “Red River’s Tannie and Theresa” (Austin High School, Austin, Tex., 1970), in Folder U5000 (5), Austin Files, AHC.

[12] Austin Urban Renewal Agency, Brackenridge Urban Renewal Project (Austin, 1967).

[13] Interview with Dorothy McPhaul by Amber Abbas, 2005, Lift Every Voice (African American Oral History Project), clip 3.

[14] Thomas W. Shefelman et al., Waller Creek Master Plan: Phase B Program Development (Austin, 1975).

The views and opinions expressed in this article or video are those of the individual author(s) or presenter(s) and do not necessarily reflect the policy or views of the editors at Not Even Past, the UT Department of History, the University of Texas at Austin, or the UT System Board of Regents. Not Even Past is an online public history magazine rather than a peer-reviewed academic journal. While we make efforts to ensure that factual information in articles was obtained from reliable sources, Not Even Past is not responsible for any errors or omissions.