From the editors: This interview was first published in 2018 by the Toynbee Prize Foundation. Named after Arnold J. Toynbee, the foundation seeks to promote scholarly engagement with global history. The original interview can be accessed here. This interview is published here as part of a new collaboration with the Toynbee Prize Foundation. The collaboration aims to share these important long form interviews with key historians working today.

To further our understanding of the development of industrial capitalism over the past two centuries Greg Cushman claims, we need to write histories ‘from below,’ in two senses: first, we need to write histories that consider not just those who ‘invented the steam engine’, but those which trace the origins of the steam engine’s parts (material and intellectual) wherever across the globe that leads us – often far beyond the ‘Global North’. Second, we need to investigate our planetary history below the earth’s surface. Lithospheric history Cushman calls it. That entails researching the history of rock and mineral extraction from the lithosphere and tracking the movement, use, transformation and impact of those materials upon humanity and the earth’s environment over millennia. He also claims that it entails taking elemental history seriously, that is, historicising the relationship between humankind’s understanding of the extraction and application of a chemical element or compound upon the earth’s environment. These trajectories are big and bold and they challenge forms of disciplinary knowledge historians presume they should master, but they’re exactly the type of interdisciplinary lines of enquiry that Cushman has been pursuing since his days as a doctoral student at the University of Texas, Austin.

In this interview, we spoke with Cushman about how he was initially drawn to excrement and elements: guano and phosphorous in particular, as he wrote his first monograph, Guano and the Opening of the Pacific World: A Global Ecological History (Cambridge University Press, 2013). We discussed the ways that paying greater attention to oral testimonies as historical evidence as well as tracing individuals and genealogies were fruitful means of keying-in on the lived-experience of historical events. We discussed how coral reef sediment cores might open up new paths in Pacific World history. We also spoke about Cushman’s career as a historian from the humble roots of his interest in environmental history with the birds that roam free on the Salton Sea in Southern California to his attempts at diversifying the reading lists at the University of Kansas where he now teaches.

Gregory T. Cushman is Associate Professor of International Environmental History at the University of Kansas, where he teaches courses on Latin America, science and technology studies, and the global environment. His first book Guano and the Opening of the Pacific World: A Global Ecological History (Cambridge University Press, 2013) received four awards, including the Turku Book Prize from the European Society of Environmental History and Rachel Carson Center and the inaugural Jerry Bentley Prize in World History from the American Historical Association.

– Sean Phillips, Toynbee Prize Foundation

First of all, I thought we could discuss how your first monograph, Guano and the the Opening of the Pacific World came into being. How was it that you came to specialise in Latin American and environmental history and how did guano become the central theme in your first monograph?

Let me start with my interest in Latin American environmental history. I’ve had an interest in human relationships with nature for as long as I can remember. My parents and grandparents are naturalists. One of the abiding memories from my childhood was visiting my grandparents in Southern California. We’d spend hours heading out to the Salton Sea, an environmental disaster area where the Colorado River escaped a canal construction system (Donald Worster details this phenomenon in Rivers of Empire), flooding the space below sea level, creating (from the perspective of birds at least) a paradise. I’ve long had this intrigue in the natural world as a result. I began studying to become an ecologist at university and it was there I discovered environmental history. I loved this idea that instead of trying to remove humans from studies of the environment, we could place them at the centre in our attempts to understand the natural world. It seems the discipline of ecology has caught up with this idea in the past couple of decades, partly due to the fact that developments in the environmental humanities have pushed them to.

As for Latin American history? My father lived in Southern Mexico before I was born and took us on trips there afterwards. I later travelled to Peru in the company of the late Dr Charles Teel who specialised in the sociology of religion. That was as a part of a study abroad trip, and it was then that I went to the Peruvian coast for the first time.

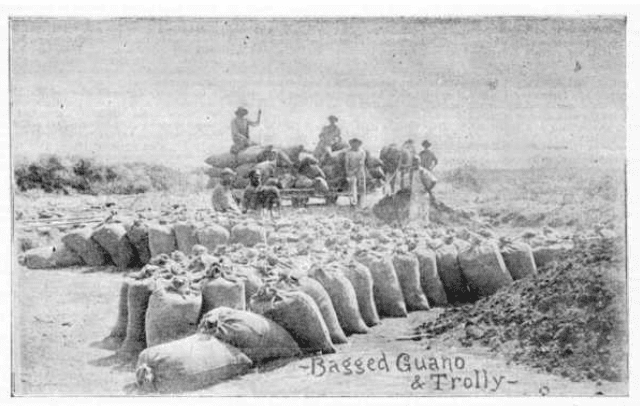

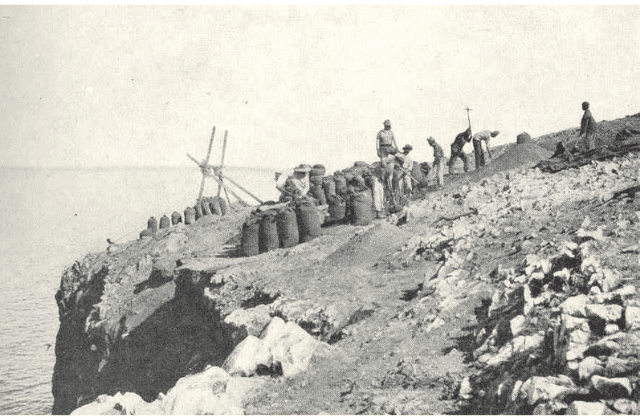

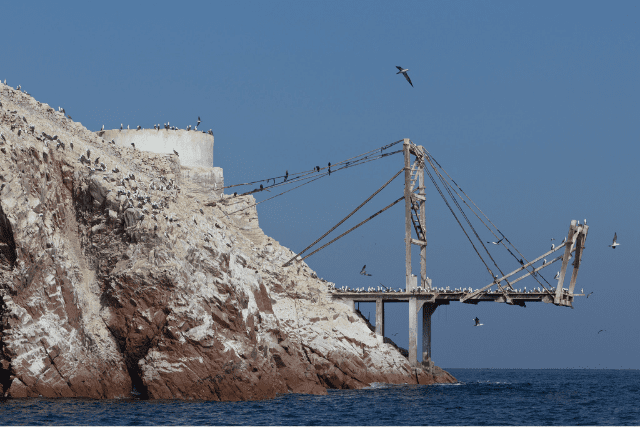

As for guano, this is really a classic subject for the economic history of Latin America, particularly for those associated with the dependentista school. Scholars had mentioned that guano was bird excrement and that it originated from marine birds (occasionally getting the species wrong), but the question really started out as: what was the story with the birds? If thousands of people, thousands of ships went to remote islands in the Pacific to collect this stuff, what ultimately became of the birds nesting there? Truthfully, I was expecting this to be a short and sad tale: miners turn up, push the birds out, eat them, perhaps leaving a desert without guano or guano birds. This was true only for a very brief moment, however. The radical discovery that kick-started this project was made when I searched for ‘guano’ in my university’s online database. Out spilled countless references to documents about guano. Not simply those dating from the so-called ‘Guano Age’ that the book begins with, but also to documents with a far more recent history in the twentieth century. After the old guano had been mined out, the Peruvian state (in collaboration with international scientists and agribusiness) started a great campaign of wildlife conservation for the benefit of both birds and humans that protected the living population of guano birds, recognising that their daily production of guano could be used for concentrated fertiliser. This story – which was so unexpected, but for which there was a wealth of source material to draw from – set things in motion.

For those who are unfamiliar with the book’s central thesis or theses, can you describe what Guano and the Opening of the Pacific World is all about?

I’d encourage readers to read the introduction to the book which outlines the seven central theses the book is anchored by. As the Pacific slowly became a known space to European and Neo-European peoples, they began to interact more intensely with the Pacific environment. This was a transformative moment and my book investigates the role of guano in this transformation. To comment more broadly on some of the questions the book seeks to explore: the book is about the place of bird excrement and excrement more generally in modern environmental, geopolitical and cultural history. I was fascinated from the very beginning with trying to explain what guano meant to the people that interacted with it. International scientists were an important group (both those from outside Peru and within) that revealed the centrality of guano in institutionalising marine science in Peru. Tracking those characters, the project quite naturally spread from Peru across the Pacific Ocean and beyond. I was truly interested in what was going on out there and what underlay this empirical discovery. I didn’t initially set out to write a global history.

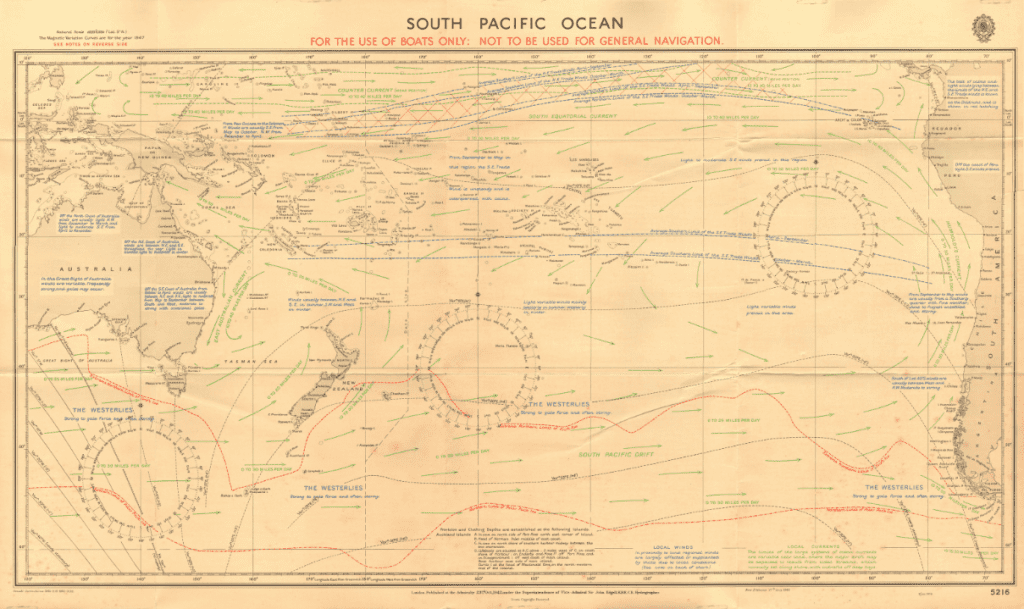

Another fundamental starting-point was the Pacific Ocean. The Pacific covers more of the surface of the earth than all the continental landmasses put together. The Pacific contains a huge amount of water. It impacts global climate, as with El Niño events. So I asked myself, what was the impact of the beginnings of the extraction of commodities like guano, whale oil, spermaceti wax, coconuts and the interaction of Neo-Europeans with peoples living in the Pacific Basin? What was the story of extractive practices upon populations, where many Pacific Islanders became slaves and semi-coerced labourers? It seemed that suddenly the possibilities of what outsiders could do were opened up from the late eighteenth century onward, not unlike what had happened in the Americas centuries before.

One of the things you do in Guano and the Opening of the Pacific World is to put forward one way of writing a history of the Pacific World. What prospects do you see going forward for histories of the Pacific World?

I think the Pacific World concept is something we shouldn’t take too seriously. The ‘Atlantic World’ was a powerful concept for helping those who studied Latin American, African and particularly North American history to re-think the boundaries of their subject and to make the slave trade the centre of understanding for the early modern period. That was enormously valuable. We increasingly find, however, that this concept has its limitations. The Pacific World can also be a valuable frame for helping us think of the world in different ways, but it inevitably has similar limitations – much like Braudel’s Mediterranean World – in that these are artificial boundaries placed around a subject to help make sense of what we perceive as emerging.

What are the prospects for the concept and for future studies? Well, we need to understand first and foremost that the idea of the Pacific World as a coherent region is something both incredibly old but also eminently modern. There are two historical phases of Pacific World history. The first, we might call the history of Pacific Islanders – not only that of the Polynesians, who travelled furthest into this world, but also of the Micronesians, Melanesians and also the Austronesians who settled New Guinea and Australia. This takes us back 65,000 years into the past. This ancient history is not something that is only knowable by documentary records, but there are a number of sources we can use to reconstruct this pre-documentary past. First and foremost are natural or physical archives with which we can investigate how the environment has changed. An archive that the Pacific has in abundance are coral reefs. In my own work I’ve used data from reef cores to understand when extreme El Niño events have occurred.

Historians have also given nowhere near enough attention to the oral histories of Pacific peoples both in the recent past (the past 200-300 years), but also as a part of older ethnic histories reported in indigenous languages. In Guano and the Opening of the Pacific World, I made use of oral traditions coming from the people of coastal Peru and the people of Banaba, a small island in the equatorial Pacific, once home to gigantic phosphate mines and a notorious case of extractive imperialism by the United Kingdom and their former Dominions, Australia and New Zealand. Banaban indigenous intellectuals have attempted to write down their oral traditions to preserve them but also to contextualise them, to investigate their culturally specific meanings. This means we have an archive that stretches back much farther than those tales of whalers from the early nineteenth century.

Lastly, it’s important to note that sometimes documentary records can be re-examined for new insights. There’s a remarkable archive concerning the conquest of Rapa Nui (Easter Island) preserved in the Routledge Papers at the Royal Geographic Society in London. Many have obsessed over the images contained in this collection, but there’s far more to gleam from the ethno-histories that Katherine Routledge was able to jot down.

For the modern period and for prospects of histories of the industrial era, the Pacific World concept helps us to think, not just of the Pacific as a place populated with thousands of islands, but of the ocean itself. This is perhaps the concept’s most useful intervention. While slavery is at the centre of Atlantic World history, I’d argue that the ocean environment is the central factor that binds the Pacific World – not just because of the resources that come from the Pacific, but also how people interact with the ocean space and with island environments. Lastly, I’d point out that it helps us think of what is on the boundary of the Pacific. One of the central arguments of my book is to demonstrate how important Latin America is in Pacific history. Chile, for example, made efforts to colonise peoples and islands in the Pacific, claiming not only the Juan Fernandez Islands, but also Rapa Nui (or Easter Island). Latin American specialists have not given nearly enough attention to these dimensions. They also haven’t adequately looked at Latin American connections across the Pacific with Japan, China and Australia, for example. These are avenues that can be mined for riches in terms of understanding the full parameters of world history.

The type of history you advocate is big and bold. How might more junior students and academics attempt histories of the Pacific World where boundaries (logistical, financial and temporal) might limit the scope of their project?

Let me propose a ‘Hitchhikers Guide’ of things to bear in mind: firstly, archival materials dealing with the Pacific are scattered amongst the conventional archives we find when researching any other regional history. The materials I used to study guano were found in the Latin American collections of the University of Texas, Austin based on Peru’s interest in the Pacific World and its environment. Archival materials from Pacific Islands themselves are available for those who have access to inter-library loan. Many materials have been microfilmed. The Pacific Manuscripts Bureau at Australian National University in Canberra organised a large-scale project to microfilm Pacific materials found around the world. Another place we might look are the transnational corporations that had interest in trading in the Pacific. The Arundel Papers which are still held privately were revealing for my own project and could be sent to your institution, for example, on microfilm. In my opinion, the Pacific may be as accessible as any region because of this. Keeping in mind that a project can get very big, very fast, one needs to construct constraints. One thing to do is to embrace the merits of following individuals, commodities, companies, imperial projects, climatic phenomenon, or actual organisms like sperm whales and sea cucumbers… so on and so forth. These can provide a way of piercing the vastness and somehow deflating the Pacific World.

Guano and the Opening of the Pacific World details the histories of a myriad of fascinating characters: from John Arundel who you’ve just briefly mentioned to Chayhuac, the ‘Lord of Fish.’ I read you have personal, family connections to the history of guano mining in the Pacific. What role was it that your ancestors played in this story and what ethical questions did this pose when effectively writing family history in a big project like this?

First of all, I would point out that tracing family histories (not only of my own but of others) was an important aspect of the methodology for this book. Once I had identified an important person, identifying their family members and tracing their histories became of interest. Given that the book ends in the very recent past, the chances were that family members were still alive. In the case of John Arundel, I was able to track down his great grandson who was still in possession of the family archives and who kindly let me reproduce a couple of photographs for the book project. So oral histories became important, particularly listening to testimony of those engaged in the late twentieth-century Peru guano and fishing industries. I was able, for example, to track down the widow and daughter of a really interesting character whom I explore toward the end of the book: Enrique Ávila – a man of indigenous descent who grew up as the son of peasant farmers near Lake Titicaca who became an assistant to an international scientist studying guano birds and then used that connection to undertake graduate studies in the United States with Aldo Leopold before returning to South America as a professional scientist. Detective work was required, but I was able to track his family down. Betsy Ávila kindly provided me with photographs and even lent me her personal family archive, which traced his work as an indigenous man trying to make it in a white world. It revealed the intense racism that he experienced – not only when he left Peru, but also while he was working in Peru. It’s quite a sad story, ultimately, but an intriguing one nonetheless.

To get to my own family history, I discovered by happenstance that I had family connections. I mentioned earlier that I typed ‘guano’ into a computer database in Austin, Texas. When I moved to the University of Kansas, I did a similar thing and typed ‘guano’ into the system and was shocked to see Henry Wyles Cushman, A Treatise on Guano appear – a pamphlet published in the mid-nineteenth century. This pamphlet was circulated among farmers in Massachusetts and detailed the virtues of guano for healthy pastures and stronger harvests. In short, a piece of agricultural propaganda. I saw the name and thought it looked familiar, so I asked my parents about it. Fortunately, my family have an interest in genealogy and we often recount stories about our ancestor, Robert Cushman (one of the key figures from the Plymouth Colony) around the table at Thanksgiving. Through the discovery that we were indeed related, it made me think…. He’s not that important as a societal figure; he was simply a farmer who advocated the use of guano among his peers, yet, for the purposes of the book he embodied the kind of connectivities all of us have who have moved from place to place around the world, either as conquerors or colonisers, as migrants or slaves. We can potentially write the stories of any of our ancestors into these histories. I didn’t set out to write the history of my family, but that story emerged from the sources. I paid attention to those stories, because it enabled me to connect myself to the story in a way that was similar to the way I was connecting other actors in the story.

It’s been a few years since Guano and the Opening of the Pacific World was published. How would you evaluate the reception of the book? Is there anything you might have done differently?

One of the things that readers have liked the most is the exact thing that many readers have liked least. That is, its vast expanse in terms of geography, time, actors and processes. The book is about guano, and guano provides some structure to the book as a whole, but guano also serves as an entry point to understanding the history of other commodities that are important to the ecological history of the modern world. These connectivities have enthralled some readers, but have challenged others looking for a tighter narrative with a smaller cast of protagonists, narrated in a conventional way. This isn’t what the book is about. I used vignettes in each chapter to elucidate stories, such as Mouga, a Niuean guano miner who loses his brother while mining guano and uses the funds that he made from the industry to get married in a traditional way. We know this because John Arundel cared enough about his story to write to him. What’s often disconcerting to readers is that they can’t place where they are. Critics of the book have said that the book is everywhere but nowhere. The more I thought about this, the more I thought this was a valid criticism of the book. But the way in which the book compels you to think about the world and to think about guano and empires and individuals in different ways is also its biggest contribution. It doesn’t seek to narrate these stories in the conventional way. In this sense it’s a history of ‘following’. When a story switched languages from Spanish to English or English to Tahitian, I didn’t let that stop me. I never became fluent in Tahitian, but I sought help for translations that were usable. To not be content to stop with the usual boundary lines that we place around our histories was key. This makes the book daunting at times, but it also means that it makes a significant contribution as a result. This does not mean, however, that I advocate writing narratives of complexity for the sake of complexity. It’s done with a purpose. The connections made in this book would not emerge in the same way if this was a biography of John Arundel or a company history of Burns Philip, for example.

You make a strong case for taking the role of guano seriously in histories accounting for the development of industrial capitalism. It seems your current work on the Anthropocene is an extension of this broader topic. Can you tell us a little about your current research projects?

I’m currently writing a book entitled The Anthropocene: A Global History of the Earth Under Human Domination, with the words ‘earth’, ‘global’ and ‘domination’ being rather emphatic terms in the title. This project is definitely an outgrowth of the guano book, but it’s also an attempt to comment more broadly on the history of the global environment and the ways industrial civilisation has made use of nitrates, phosphates and commodities more broadly and how they impact the environment. It’s a study of the history of people living within industrial civilisation, a study of our relation in particular to the chemical elements. For example, nitrogen is crucial to the creation of amino acids and proteins. If there’s no nitrogen, there’s no means to bond amino acids together. Nitrogen is thus critical to the history of protein-rich food we eat, in particular, meat. One sad discovery in writing the guano book was the way Peruvian planners intentionally decided to let the guano industry decay to exploit fish supplies to make chicken and hog feed for export abroad.

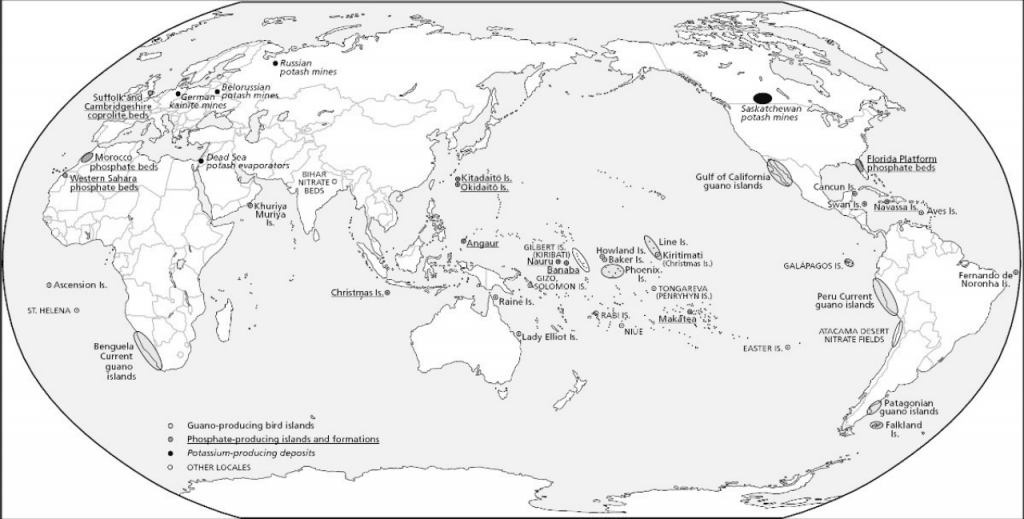

In the broadest sense, elements provide an entry point into thinking about the Anthropocene. For those that are unfamiliar with the concept, the Anthropocene is the proposed name for a new geological epoch in which humans are the fundamental causal agents that have transformed earth-systems to such an extent that the earth operates in a recognisably different way. As a result, these transformations are leaving a mark on geological strata that will far outlast us. We are leaving a mark not just on our climate, but on the rocky crust, the physical earth itself. One of the ways of exploring this is exploring different isotopes, examining the various minerals being deposited. Climate change is going to have a great impact in the future. But nitrogen and phosphorus from concentrated fertilisers have already had as great an impact upon ecosystems as anything else, thus far. This led me to think about other phenomena that also leave a mark: burning coal and other fossil fuels, investigating lead and other heavy metals, along with the radioactive isotopes produced by atmospheric nuclear testing and by nuclear energy facilities. I became interested in the different chemical elements involved in this.

The Anthropocene is not only a major topic for earth scientists, but also for students of history and the environmental humanities in terms of thinking about the mark that industrial civilisation is leaving on the planet. One of the realisations I had in thinking about these different material processes and of the substance of these materials was how practically all of them are extracted from the lithosphere. This involves investigating the exploitation of things as humble as sand, cement, gravel, and asphalt, bearing in mind how important these materials are for building things. This has become a central line of enquiry in my new project. The new relationship that industrial civilisation has developed with the lithosphere and with the inorganic world–what we used to be call the ‘mineral kingdom’–lies at the heart of this.

Something that’s abundantly clear both from Guano and the Opening of the Pacific World and your past publications is an appetite for interdisciplinarity. In your latest project, it seems you’re advocating or attempting to practise elemental history, historicising the relationship between humankind’s understanding of extraction and application or use of chemical elements or compounds, and their impacts upon the earth’s environment. Am I correct in suggesting you’re trying to spearhead a new direction in global history in this sense: one that fuses physical science (particularly chemistry) with environmental sciences and history? This seems a fascinating proposition, but one which will require new skills as well as an ability to bring historians into closer conversation with an even wider variety of academic disciplines.

You’re keying in on some of the exact motivations for adopting this lithospheric perspective of human history. This book is a study of the diversity of human relationships with the lithosphere over time, not just industrial civilisation and not just in the Global North, but going back to the Stone Age. I want to explore how our manipulation of flint and hard stone was critical for our earliest ancestors. I’ve been looking under every rock (so to speak), but except for histories of mining, historians have not yet taken a rock-focused perspective on history. This is a way of contributing something new to the historical profession. What I mean by lithospheric is not simply to stop with where the stuff comes from (the lithosphere), but also by explaining how and why it has been extracted from that context. Lithospheric history is very much about extractivism as an ideology and practice in human society (especially capitalist society). Once something has been extracted, we should ask how it moves, what its new uses are and how it’s processed. When it comes to the Anthropocene, we need to ask what mark these processes make once they leave our view, when they become waste or ruins, for example. Tracing the life histories of the elements is very much a part of this. I very much like this idea of an elemental history that you propose for describing this.

To provide you with a tangible example of how this works, I’ve been engaged recently in a project called the Phosphorous Apparatus with Zachary Caple and Katerina Teaiwa and others. We’ve been thinking about the place of the chemical element phosphorus in contemporary society. Zac especially is interested in the phosphate mines of Florida and what happens when they are incorporated into the Plantationocene. Katerina is Banaban by ethnicity, born on Rabi Island in the Fiji archipelago, which is the new home of her people. Following phosphorus through our lives has been one approach, but it’s a useful unifying solution to hone in on one particular substance, thing or material, or object.

‘Phosphorus, Guano and the Opening of the Anthropocene’, a presentation by Greg Cushman at Phosphorus: An Apparatus of the Technosphere, Haus der Kulturen der Welt Berlin, 2 October 2015. Video: Haus der Kulturen der Welt

One other element I’d add to this lithospheric or elemental perspective on the history of the Anthropocene is that I’m emphatic that these histories have to be histories from below and of the whole globe, not just histories of the industrial North. One of the things I’m most proud of in the guano book is the extent to which that history – the history of guano in industrial civilisation – is grounded in Peru and the Pacific Islands. Using the same methodologies, I’m setting out to write this book, grounded not just in the histories of the ‘builders of the steam engine’, but also where the substances come from, analysing the extent to which subaltern peoples have been involved in creating industrial civilisation from the beginning: as builders, as providers, as labourers, as consumers, as the builders of networks, as immigrants. It’s a long list.

This gets us into the question of interdisciplinarity as well. I’ve been engaging heavily with geologists and geo-archaeologists to learn more about the lithosphere itself as an object of study. I’m not going to be able to make soil cores and derive the isotopes to reconstruct the agricultural history of a place, but I can understand enough to be able to read articles they produce to understand that phenomena are not simply the product of recent history. The so-called ‘Great Acceleration’ began a lot earlier than is sometimes claimed – long before 1950. Adopting histories from below also means that we diversify our perspectives on the world and the types of source material we use to reconstruct the past. Global history has in many ways been written from the top-down thus far. Ecological Imperialism, for example, is mainly the history of the actions of European-derived peoples and their alliances with microbes, mammals, crops and pests. Al Crosby, who was originally one of my teachers as a graduate student, ultimately wrote that history from the perspective of people like himself and like me. We need to make a concerted effort to write histories which include the rest of the world, not just the peoples, but also their biota, even the inorganic matter of the earth itself. I’m hopeful that people who read my work will find inspiration in writing a more diverse set of histories and accepting that individuals matter in allowing change to unfold.

What are you currently reading and what book or article would you recommend to a graduate student as a source of inspiration?

One book I’m reading right now is Timothy Morton’s Dark Ecology: For a Logic of Future Coexistence (2016). He’s perhaps best known as an eco-critic and as an environmental philosopher. The book has really challenged me to rethink many things that I hold dear. In terms of understanding the Anthropocene, one of the issues I find most interesting is his argument that in our attempt to cordon ourselves off from nature, in a process called agro-logistics, we’ve committed an original sin. Civilisation and the epoch of the Anthropocene are one and the same as far as Morton is concerned, and all agricultural societies are culpable. At one point he claims “we remain Mesopotamians”. It’s an intriguing, but wrong-headed perspective to take on this, in my view. I do not think that Tim Morton, nor James Scott in his new book Against the Grain, nor many other historians of global civilisations have given serious enough consideration to the diversity of human societies or to the ways people living close to the land and sea have organised themselves in different ways to live in the natural world. The phrase “we remain Mesopotamians” seems to reveal that what we need, more than anything in the practice of global history, is to make a concerted effort to write from the perspective of the Global South. So many writers of global history are reformed European or North American historians. Historians starting from Latin America, Africa and the Pacific Islands need to be writing these histories as much as those from the Global North. Historians originally from these regions need to be writing them.

As for a book that had a huge impact upon me? It was the first environmental history I set my eyes upon. I was studying to become an ecologist, and had just spent a summer doing field research in marine environments at Puget Sound on the shore of the Pacific. My professor gave me an article entitled, “Transformations of the Earth: An Agro-Ecological Perspective on History”, by Donald Worster, published in 1990 in the Journal of American History. In it, he proposed using findings from ecology to look at agriculture as an institution, not just in the United States but globally. I was intrigued by these possibilities and fascinated at how we might put ecology into the histories of industrial societies and how human activities could be a focus of study for ecologists. I had no idea this was even possible as an undergraduate science student. One of the really great things about this is that I’ve ended up at the University of Kansas, one of the places Donald Worster spent so much of his career.

It’s also worth mentioning that we need to continually return to the classics and foundational texts of whatever field it is that we study, not only in remembrance of where we come from intellectually, but also because when we look at these works with new eyes and perspectives, we spot things that haven’t been fully pursued or developed. When I teach Latin American history, I assign ‘classics’, but classics by Latin American thinkers, such as Gilberto Freyre’s The Masters and the Slaves, José Vasconcelos’ La Raza Cósmica (The Cosmic Race), Yo Rigoberta Menchú, and the idea of ‘civilisation and barbarism’ as defined by Domingo Faustino Sarmiento in Facundo. The key is to read texts coming from other regions and traditions, even if they’ve been written by elites. Find reviews in your own language. Teaching from a classic text approach means to engage with texts and with thinkers that we have found value in because they’ve been important in the creation of the world we live in, but to do so in a way that radically expands the “canon” of works we consider. Pairing those with texts and thinkers from the outside and placing them in dialogue: this is one of the most valuable things we can do.

The views and opinions expressed in this article or video are those of the individual author(s) or presenter(s) and do not necessarily reflect the policy or views of the editors at Not Even Past, the UT Department of History, the University of Texas at Austin, or the UT System Board of Regents. Not Even Past is an online public history magazine rather than a peer-reviewed academic journal. While we make efforts to ensure that factual information in articles was obtained from reliable sources, Not Even Past is not responsible for any errors or omissions.