by Christopher Heaney

This weekend, as Cairo’s protestors struck their tents and tidied up Tahrir Square, a clean-up operation of another sort was underway nearby: in the Egyptian Museum, home to King Tutankhamen and countless other archaeological treasures.

The museum had haunted the protests since they began in late January. In the first few days of the unrest that toppled President Hosni Mubarak on Friday, newspapers were quick to note that a group of looters had broken through a skylight, apparently searching for gold. Although Tut’s famous mask was thankfully under lock-and-key, the intruders knocked over or damaged approximately 70 artifacts. In one of the many exciting turns of the last several weeks, however, Egyptian neighborhood patrols surrounded the museum and caught the would-be thieves.

“I’m standing here to defend and to protect our national treasure,” one man told the AP. “We are not like Baghdad!” shouted another. The looting of Iraq’s National Museum in 2003 was on every observer’s mind.

The Egyptian military arrived soon after, took the looters into custody and made the museum a base of operations. Just outside, Tahrir Square became the protests’ center. It seemed to be a victory for Egypt’s people and its military.

“If Cairo museum and the pyramids are safe, Egypt will be safe,” said Zahi Hawass, Egypt’s Minister of Antiquities, The National Geographic reported. “Inspectors, young archaeologists, and administrators, are calling me from sites and museums all over Egypt to tell me that they will give their life to protect our antiquities,” he further claimed. Countless political cartoonists, meanwhile, depicted a sphinx-like Mubarak losing his nose, or tumbling from the pyramids.

On Saturday, however, Hawass revealed that not all in the house of Tut was as well as he had claimed. Confirming what many Egyptologists suspected, Hawass reported that 18 objects have disappeared, including two gilded statues of the boy pharaoh, as well as an image of Nefertiti. A Twitter campaign is now calling for Hawass’s investigation, and a march for his resignation is apparently being planned for Wednesday.

Before commentators perpetuate the inevitable comparisons to the National Museum of Iraq, it is worth remembering the difference in scale – upwards of 15,000 artifacts lost in 2003. But, more importantly, Egypt has a long and complicated history of the protection of ruins and artifacts. In times of transition, that history is felt keenly. For millennia, new governments in Egypt – dynastic, foreign and national – have had to re-build the country’s monuments and mummies, often aware that the rest of the world was waiting to collect the pieces.

Of Strongmen and Mummy Powder

Egypt’s fear of such loss is as ancient as the pyramids. Egyptians of the Old Kingdom, the third millennium BCE, spent much effort protecting their monuments and tombs from the malice of future regimes. Pharaohs built “dummy chambers” to hide their mummies and nobles engraved their statues with bawdy warnings such as: “Whosoever should deface my statue and put his name on it … let Emil, the lord of this statue and Shamasg tear out his genitals and drain out his semen. Let them not give him any heir.”

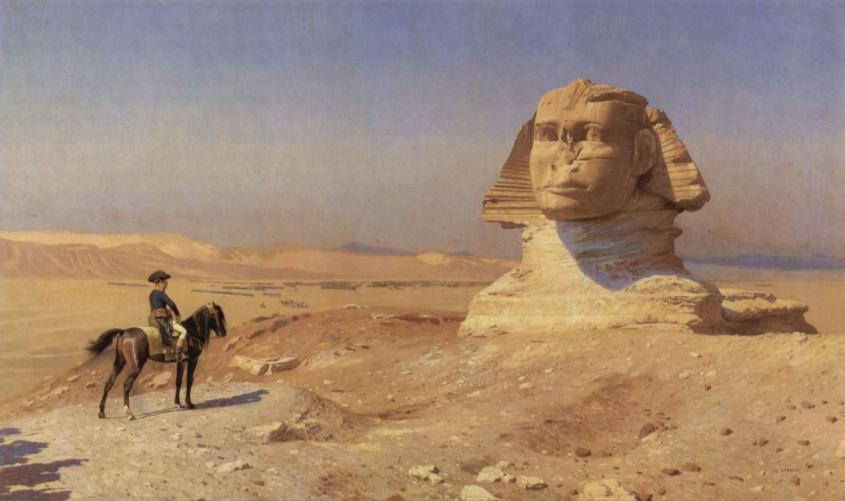

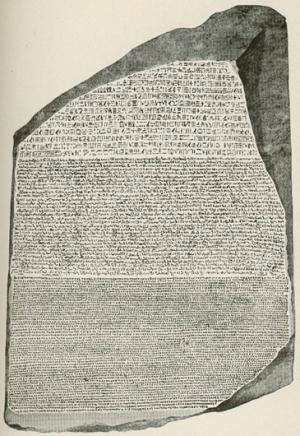

Millennia later, Arab, Mamluk and Ottoman rule saw a healthy trade in books that claimed to reveal the treasures of forgotten tombs. Digging up mummies proved more profitable, however. To feed European hunger for “Oriental” secrets and medicine, traders shipped the ancient dead to Italy, where they were bought and sold as mumia – ground-up mummy — used as a medicine and sometimes as a color in painting.  Antiquarianism during the Renaissance and Enlightenment again made Egypt an object of desire. When Napoleon invaded Egypt in 1798, he brought along a bumptious team of French savants who sketched ruins and collected artifacts for the Louvre. France capitulated to England, however, and the British Museum got the vast majority of Napoleon’s spoils, including the famed Rosetta Stone. (The French savants, for their part, first threatened to throw it all in the sea, rather than turn the prize over to their enemies.)

Antiquarianism during the Renaissance and Enlightenment again made Egypt an object of desire. When Napoleon invaded Egypt in 1798, he brought along a bumptious team of French savants who sketched ruins and collected artifacts for the Louvre. France capitulated to England, however, and the British Museum got the vast majority of Napoleon’s spoils, including the famed Rosetta Stone. (The French savants, for their part, first threatened to throw it all in the sea, rather than turn the prize over to their enemies.)

In 1835, Egyptian authorities established the Antiquities Service of Egypt to staunch rampant looting by locals and Europeans like “The Great Belzoni,” a former circus strongman from Venice who hauled out busts and obelisks by the ton – a tale laid out in rollicking, lacerating form by archaeologist Brian Fagan in The Rape of the Nile: Tomb Robbers, Tourists and Archaeologists in Egypt. Under the system that developed, only scientific experts could excavate and half of the artifacts they found would stay in Egypt – a system called “partage.”

As in all archaeologically-rich regions, however, enforcement proved hard. Locals continued looting to supply growing tourist demand, British archaeologists saved key artifacts for their patrons, and French and Egyptian employees of the Antiquities Service sold pieces from the museum on weekends. Egyptian train conductors used mummies for fuel, Mark Twain claimed. Somewhat hypocritically, Europeans and Americans cast the dysfunction of Egypt’s antiquity system as a further rationale for England and France’s informal rule: if Egyptians couldn’t protect the treasures of their past, the logic went, they weren’t ready to govern themselves.

National Foundations

Yet this wasn’t the entire story. Kept out of Egyptology by the British, Egypt’s Muslim intellectuals engaged in an Arab humanism ignored by history until only recently. They found work in the Cairo Museum – opened in 1902 – and led the study of Coptic and Islamic architecture and art. “It is not fitting for us to remain in ignorance of our country or neglect the monuments of our ancestors,” Egyptian scholar Alu Mubarak wrote in 1887, as quoted by Donald Malcolm Reid in Whose Pharaohs?: Archaeology, Museums, and Egyptian National Identity from Napoleon to World War I. “For what our ancestors have left behind stirs in us the desire to follow in their footsteps, and to produce for our times what they produced for theirs; to strive to be useful even as they strove.”

When the country achieved independence in February 1922, nationalists used Cairo’s Museum and foreign archaeologists to debate continuing British influence. In November of that year, American Howard Carter, funded by England’s Lord Carnavon, made his famed discovery of King Tut’s tomb. In the media circus that followed, newly independent Egyptians protested that the English and American team was being too secretive and perhaps moving artifacts to England and New York. Egypt eliminated the “partage” system and claimed all excavated objects, to Carter’s lasting fury.

Foreigners still loomed large over the next half-century of research, but in the years after Hosni Mubarak took power in 1981, the Egyptian Museum and its flamboyant spokesman, Zahi Hawass, oversaw a period of national consolidation. Seen as a cultural hero by some and a one-man showboat by others, Hawass focused world attention on Egypt’s past with a series of blockbuster discoveries, profitable traveling exhibits, and noisy campaigns for the return of the country’s artifacts from American and European museums. In some cases, he was successful. In November 2010, the Metropolitan Museum agreed to return its share of treasures that Howard Carter had stolen from the young pharoah’s tomb (as former Metropolitan Museum of Art director Thomas Hoving had claimed in his 1978 book, Tutankhamun: The Untold Story).

A New Start?

To use a metaphor as old as Tut, will Mubarak’s fall, and the museum’s loss of 18 objects, now shake Hawass’s own dynasty? As in past transitions, the politics of archaeology are running hot. Hawass has confirmed outside claims that looters broke into another deposit of artifacts in Egypt’s south; further losses are sure to emerge. Hawass’s affiliations with Mubarak may also cause him problems. While protestors assailed the administration in the streets, Mubarak promoted Hawass to his cabinet. Like their fellow Egyptians in Tahrir Square, the Cairo Museum’s employees are demanding higher wages and less corruption. Meanwhile, human rights advocates say that the army has detained and abused protestors either behind the museum or inside the museum itself.

Although an investigation of the Museum break-in should proceed, it is too soon to call for Hawass’s resignation. As Ian Parker of the New Yorker recently noted, Hawass is too central to Egypt’s antiquity system to lose during the transition. More importantly, it would be unfair to blame the losses on the protests themselves or to claim that Egypt’s museums have “failed.” It has been speculated that Mubarak’s secret police themselves – perhaps working with the museum’s guards – may have been behind the museum’s robbery. Hawass has vehemently denied the charge, but it provokes the question: no matter the identity of the looters, for whom were they collecting? The 18 stolen pieces were true treasures, suggesting, like the looting of Baghdad’s museum, that the job was done to fulfill the “wishlist” of a private collector, perhaps foreign.

The robbery of the Egyptian Museum and the loss of other objects from archaeological deposits around Egypt is a reminder of the shared responsibility of cultural patrimony. The protection of monuments and mummies like Egypt’s requires vigilance, not only from Egypt’s people but also from the international community whose collectors have made looting lucrative for centuries.

As the behavior of the heroic neighborhood patrols who detained the looters attests, Egypt seems to be holding up its side of the bargain. It’s a small comfort, but perhaps the theft of only 18 of the museum’s objects is a victory, given past losses. It’s time that the rest of us do the same, respecting just what Cairo’s museum and its history represent to the Egyptian people. A former Arab diplomat has characterized the last month as “Facebook meets the Egyptian Museum.” As we read newspapers online and scrutinize photos of celebrations in Tahrir Square, we should cheer the fact that Cairo’s museum, and the history it represents, is literally that victory’s background.

Sources: The pharaoh’s ancient curse is cited in Z. Bahrani, “Assault and Abduction: The Fate of the Royal Image in the Ancient Near East,” Art History 18 (1995).

Further reading:

An online exhibit on the Napoleonic scientific expedition in Egpyt by the Linda Hall Library.

Another AP article on the museum’s looting.

Mummies as medicine via Wikipedia, Scientia Curiosa and Res Obscura.

Former diplomat Charles Wolfson on Egypt’s future, via CBS news.

Photos of the Egyptian Museum interior and exterior by Kristoferb (Own work) [CC-BY-SA-3.0 (Wiki Commons)]; of Zahi Hawass in Northern Egypt, 8 May 2010, VOA News; Rosetta

Stone: public domain; Napoleon Before the Great Sphinx, by Jean-Leon Gerome; Howard Carter at the tomb of Tutnakhamen, by Harry Burton via Wiki Commons.