By Mary Neuburger

The global history of tobacco—the weed that captured the hearts, minds, and imaginations of so many in the twentieth century—has been told in splendid and enlightening detail. Historians have delved into the stark economic, political, and social implications of the production, consumption, and exchange of this commodity in various national contexts, most notably the United States.

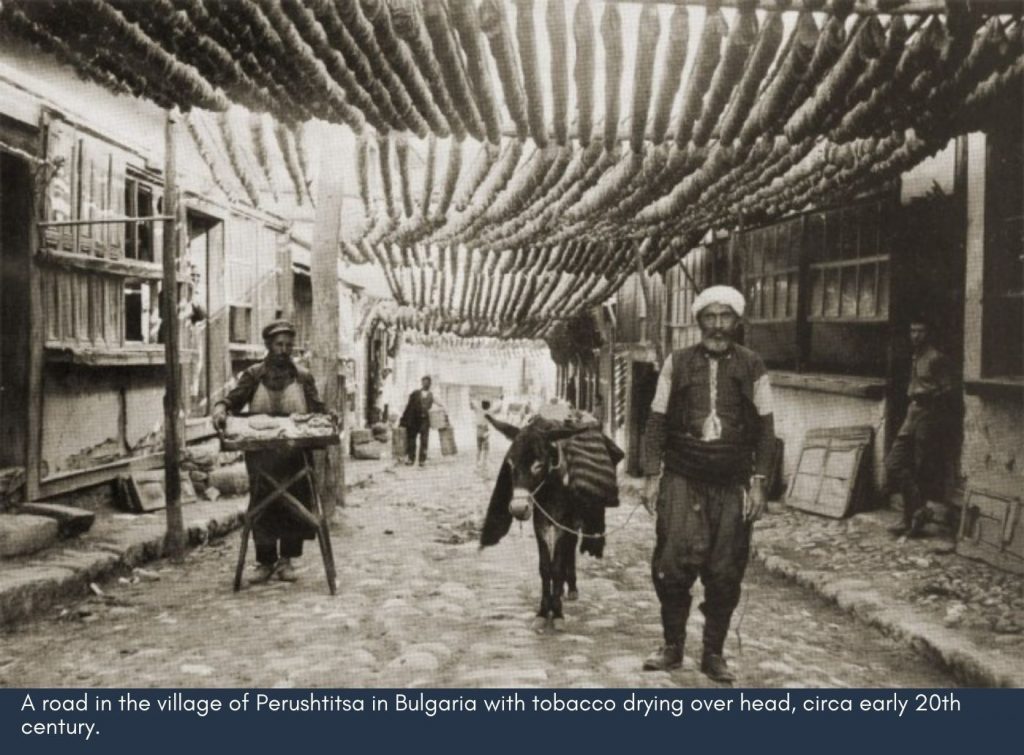

In writing Balkan Smoke, I wanted to explore the ways tobacco drove historical transformation in Bulgaria, a place often left out of these global histories. On the periphery of Europe and Asia, and in the path of various geopolitical interests, Bulgaria became a tobacco “center” of its own in the twentieth century. Balkan Smoke explores Bulgaria’s global economic and political entanglements via tobacco, with the Ottoman Empire, Central Europe, The Soviet Union and the Bloc, and the West, including the United States. From provisioning the Ottoman Empire (which Bulgaria was a province of until 1878), to supplying Nazi Germany and then the Soviet Union, by the 1960s Bulgaria became the largest exporter of cigarettes in the world.

A prodigious literature has also outlined how tobacco—as one of the global “big three” drugs of choice along with alcohol and coffee—has served as a central chemical palliative in the modern era. Tobacco—brought to Europe, the Near East, and the rest of the globe from the New World—seduced consumers but also provoked public scrutiny and debate. Perhaps in part this was because smoking rituals moved west from the “Orient”—more specifically the Ottoman lands. Oriental-style smoking rooms, for example, became an escapist symbol of wealth and excess for the West to emulate, appropriate, and domesticate.

This was also true of the more public coffeehouse institution, and coffee itself, that was directly imported from the Ottoman Near East to Western Europe beginning in the seventeenth century. As many scholars have argued, smoking played a role in new patterns of consumption, commerce, sociability, and even political mobilization in the West. In the Ottoman lands, the smoke-filled coffeehouse had also played similar roles, but with peculiarly local patterns.

Specifically, smoking and the coffeehouse had been always firmly associated with the Muslim coffeehouse, as opposed to the Christian tavern. Bulgarians were directly ruled by the Ottomans from the 15th-19thcenturies and lived among large Muslim populations. Yet it was not until the nineteenth century that they began to enter the Muslim coffeehouse, where they conducted commerce and local administration, read newspapers, and engaged in debate. It was then that they learned to smoke, as they came of age politically and culturally, and as their national movement gained momentum. Indeed, over the course of the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, smoking, like the tobacco industry itself, drove social change, accompanying and even propelling a certain “coming of age” for social groups who joined the ranks of passionate smokers.

As Bulgarians entered the coffeehouse at home, they also began to frequent European cafes and discover themselves as “Bulgarians” abroad, amidst the intellectual ferment of Paris, Vienna, and St. Petersburg. Soon Bulgarians began to establish coffeehouses at home that took on increasingly European characteristics, mainly aesthetically. For example, the traditional hookah was replaced by the newly minted cigarette. Paraphernalia became a marker of modern, European sensibilities, as coffeehouses became places of intellectual and cultural activity, and tobacco became a muse for generations of the Bulgarian elite. In the interwar period, in particular, the coffeehouse was at the heart of intellectual life, though other kinds of smoke-filled venues mushroomed in the Bulgarian capital and elsewhere in Bulgaria.

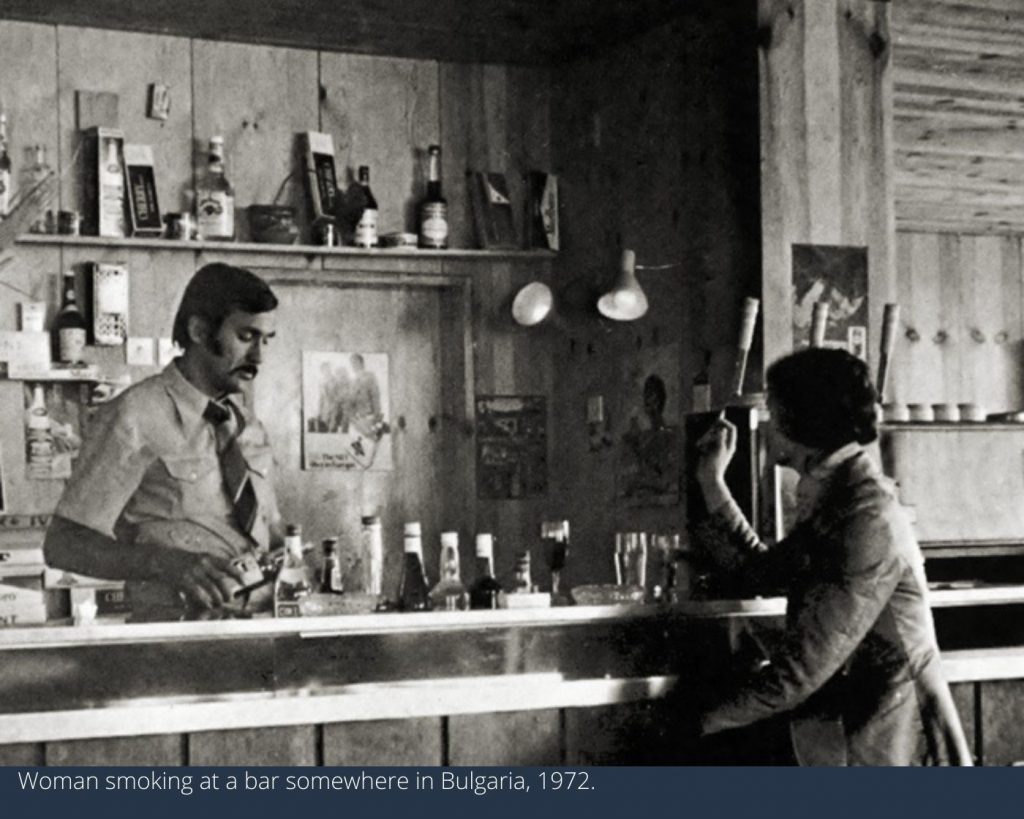

Smoking became the quintessential modern habit, a necessary accoutrement for the modern man and eventually woman, in both the sober coffeehouse and the drunken tavern. Women and youth slowly entered this world of public smoking in the course of twentieth century, a fact that impelled anti-smoking impulses (however meager).

In some respects this is a familiar story, with obvious global parallels, yet the Bulgarian context continually reveals it own particular nuances. In pre-1945 Bulgaria, for example, anti-smoking impulses flowed from two rather disparate sources, American (and Bulgarian convert) Protestants and the communist left. Both had a radical vision for “moral uplift” and social reform and utopian visions of the future. But both were also, in a sense, foreign, and so faced local and official hostility in the period before 1945. Most Bulgarians simply did not want to give up their new found pleasures, and the state was an important beneficiary of tobacco industry revenues and consumption taxes. In the post World War II period, the dramatic change to a communist form of government brought an entirely new set of practical and theoretical quandaries. The Bulgarian tobacco industry took off, producing ever greater numbers of increasingly luxurious cigarettes for the enormous “captive” Soviet and Bloc market.

There was also a veritable explosion of state built and run restaurants, cafes, hotels and sea-side resorts in the later decades of period, as the state sought legitimacy by providing the “good life” to its workers. By the 1960s and 1970s, however, communist state-directed abstinence efforts emerged, along with heightened concerns over the growing numbers of smoking women and youth. The Bulgarian communists continually connected smoking to “western” moral profligacy and “remnants” of a capitalist past, as well as “Oriental” degeneracy—or Bulgaria’s backwards, Ottoman past. Yet the state continued to provide cheap cigarettes and places to smoke them as never before. Bulgarian smoking rates skyrocketed under communism and the period generated a society of smokers for whom the voice of abstinence was just another form of state propaganda.

Since the 1989 collapse of communism, smoking is still central to leisure culture in Bulgaria. The gleaming new post-communist cafe, cocktail bar, pizzeria, and now McDonalds are still smoker-friendly. Although the tobacco industry was devastated by the transition, a 2010 bill to prohibit all smoking in restaurants, bars, and other leisure establishments failed to pass through the Bulgarian parliament. Smokers are digging in deep in order to maintain what one Bulgarian friend told me is their “way of life.” History helps us understand why, as the world gradually pushes tobacco smokers out in the cold, in Bulgaria they are still welcome inside.

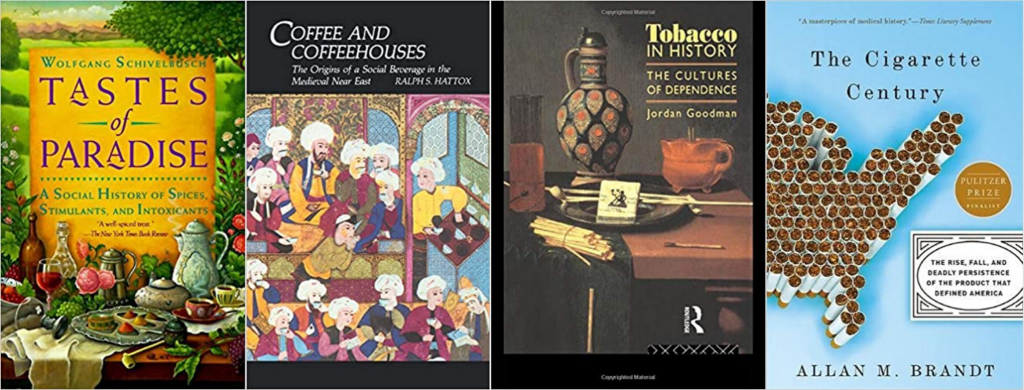

Allan Brandt, The Cigarette Century: The Rise, Fall and Deadly Persistence of the Product that Defined America (2007).

This is an excellent book for understanding the extent to which a particularly commodity, in this case tobacco, shaped American history. With a focus on the twentieth century it traces the story of the rise and fall of smoking, from a curiosity, to socially acceptability, to the war on smoking in the United States.

Jordan Goodman, Tobacco in History: The Cultures of Dependence, (1993).

Tobacco in History has more of a global reach, exploring the international dynamics of the production, exchange and consumption of tobacco. It give a wide sweep of how this one commodity shaped global history from its New World origins to its conquering of global tastes.

Ralph Hattox, Coffee and Coffeehouses: The Origins of a Social Beverage in the Medieval Near East, (1985).

Hattox’s Coffee and Coffeehouses is a classic, which provides a fabulous overview of the introduction of coffee into global consumer cultures. Specifically, he traces the role and historical implications of the coffeehouse institution from its Near Eastern origins to their European incarnations.

Wolfgang Schivelbusch, Tastes of Paradise: A Social History of Spices, Stimulants, and Intoxicants, (1992).

Schivelbusch’s Tastes of Paradise, provides a thought-provoking look at the history of tobacco, coffee, and other intoxicants, with a focus on Early Modern Europe. He makes provocative arguments about the success of particular geographic regions, namely Northeastern Europe, based on shifts in consumer culture and intoxicant preferences and habits.

Relli Shechter, Smoking, Culture and Economy in the Middle East: The Egyptian Tobacco Market 1850-2000, (2006).

Shechter’s highly original Smoking, Culture and Economy in the Middle East is one of the best context specific books on the tobacco industry and smoking that I have encountered. With a focus on modern Egypt, this book shows the kinds of unexpected impacts that a commodity can have in a distinctly colonial context.

Photo Credits

Courtesy of www.lostbulgaria.com and the Regional State Archive in Plovdiv