by Gajendra Singh

University of Exeter

Posted in partnership with the History Department at the University of Exeter and The Imperial and Global Forum.

One of the earliest films to be shot and then screened throughout India were scenes from the Delhi Durbar between December 29, 1902 and January 10, 1903 The Imperial Durbar, created to celebrate the accession of Edward VII as Emperor of India following the death of Victoria, was the most expensive and elaborate act of British Imperial pageantry that had ever been attempted. Nathaniel Curzon, as Viceroy of India, oversaw the construction of a tent city housing 150,000 guests north of Delhi proper and what occurred in Delhi was to be replicated (on a smaller scale) in towns and cities across India.

One of the earliest films to be shot and then screened throughout India were scenes from the Delhi Durbar between December 29, 1902 and January 10, 1903 The Imperial Durbar, created to celebrate the accession of Edward VII as Emperor of India following the death of Victoria, was the most expensive and elaborate act of British Imperial pageantry that had ever been attempted. Nathaniel Curzon, as Viceroy of India, oversaw the construction of a tent city housing 150,000 guests north of Delhi proper and what occurred in Delhi was to be replicated (on a smaller scale) in towns and cities across India.

The purpose of the Durbar was to contrast British modernity with Indian tradition. Europeans at the Durbar were instructed to dress in contemporary styles even when celebrating an older British Imperial past (as with veterans of the ‘Mutiny’). Indians, however, were to wear Oriental (perceptibly Oriental) costumes as motifs of their Otherness. This construction of an exaggerated sense of Imperial difference, and through it Imperial order and Imperial continuity, was significant. It was a statement of the permanence of Empire, of Britain’s Empire being at the vanguard of modernity even as the Empire itself was increasingly anxious about nascent nationalist movements and rocked by perpetual Imperial crises.

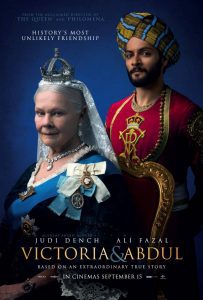

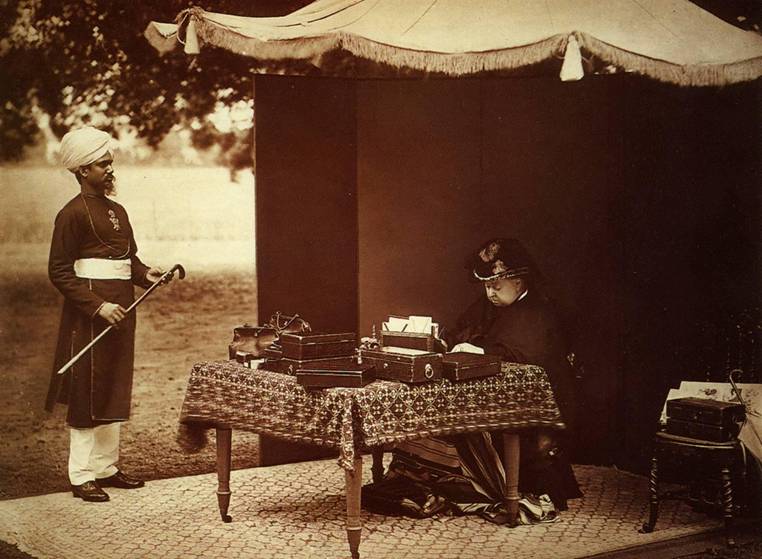

It’s unlikely that Stephen Frears watched these films from 1902 or 1903 upon finalising the screenplay and then shooting Victoria & Abdul. They have only recently been digitized and archived by the British Film Institute. But his recent movie, filmed when most visions of the past are obscured by the myopia of the present, is an unconscious reproduction of films produced and shown when Empire was an idée fixe in the British mind. Abdul Karim, one of several Indians at Victoria’s court during her long reign (the other two, that I know of, were Dalip Singh, the last Maharaja of Punjab, and Victoria Gouramma, the daughter of the last Raja of Kodagu), is a cypher throughout the film. He shows no emotion or sentiment or stirring rhetoric except when genuflecting before his Empress – kissing her feet upon their first meeting, stoically holding her hand upon her death, sitting as a sentinel by her statue in Agra into his dotage.

Such a one-dimensional portrayal is partly a reflection of the populist histories used as source material for the film. Sushila Anand’s Indian Sahib: Queen Victoria’s Dear Abdul is a titillating account of the possible sexual encounter between the matronly white Empress and her much younger lowborn Indian servant and Shrabani Basu’s Victoria and Abdul: The True Story of the Queen’s Closest Confidant is a more sober tale of the scandal that the relationship caused among Victoria’s staff. But even in these accounts Karim has voice and agency. Anand and Basu are, in part, relying upon Karim’s own accounts of what transpired when he and Victoria were alone.

Queen Victoria and Abdul Karim, 1893 (via Wikimedia Commons)

That agency is consciously stripped by Frears. His instruction to Ali Fazal upon taking up the role was to play him as Peter Sellar’s Chance in Being There, a character who is a simple-minded, sheltered gardener suddenly catapulted into political power.[1] It is Judi Dench’s Victoria and, to a lesser extent, Eddie Izzard’s wonderfully corpulent Bertie/Edward VII who are the actual protagonists of the piece. The official synopsis makes this clear:

The film tells the extraordinary true story of an unexpected friendship in the later years of Queen Victoria’s remarkable rule. When Abdul Karim, a young clerk, travels from India to participate in the Queen’s Golden Jubilee, he is surprised to find favor [sic.] with the Queen herself. As the Queen questions the constrictions of her long-held position, the two forge an unlikely and devoted alliance with a loyalty to one another that her household and inner circle all attempt to destroy. As the friendship deepens, the Queen begins to see a changing world through new eyes and joyfully reclaims her humanity.

Her rule, her favour, her humanity. It is a story told to redeem Victoria. It is through her eyes that the narrative is conveyed and any change or evolution in a character occurs in her attitudes towards India and her subject people – learning some terribly mis-pronounced Hindustani/Urdu and that Indians too can act as competent servants (huzzah!). Victoria is cast as the flagbearer of Imperial progress against her “racialist” son who despises Karim and is representative of a “bad” form of Imperialism. “If only the latter had not won out,” we are expected to cry, “then India would not have been lost!” Only in the uncovering of the fact that Karim had gonorrhoea by Victoria’s outraged staff do we get a glimpse of the many lives lived by Karim. One can only assume that he had at least some fun in England.

The film is an Orientalist fable that is not meant to reveal any social life of the Indian portrayed. But that is not what makes it remarkable. Stephen Frears made his career with My Beautiful Laundrette in 1985, a film which presented the transgressive relationship between Gordon Warnecke’s Omar, a British-Pakistani from Battersea, and Daniel Day Lewis’ Johnny, a neo-Nazi. It seems that the complex filmic relationships that were once Frears’ stock-in-trade are no longer filmable or seen as commercially viable. Instead in Abdul we have a character who is childlike in his stupor at British munificence, completely asexual despite the revelation that he has a sexually transmitted disease, and is always ready with a word of wisdom that only a true Oriental can provide (lines that are, of course, from Rumi – always Rumi). It is an unconscious reproduction of the first films ever produced of and in India. But at least in those films the desire to cast Indians into caricatures was born from Imperial anxiety; this is merely the product of an absence of thought.

Sources and Related Reading:

Antoinette Burton, The Trouble with Empire: Challenges to Modern British Imperialism (2015).

Kim Wagner, ‘“Treading Upon Fires”: The “Mutiny”-Motif and Colonial Anxieties in British India’; Past and Present, 218: 1 (2013): 159-197.

Sushila Anand, Indian Sahib: Queen Victoria’s Dear Abdul, (1996).

Shrabani Basu, Victoria and Karim: The True Story of the Queen’s Closest Confidant, (2010).

Christopher Pinney, Camera Indica: The Social Life of Indian Photographs, (1997).

UK readers can find early films of India on BFI Player here, and a full list of films from this era (with commentary by the author) here. US and international readers can see a similar film, Delhi Durbar (1912) on Youtube here.

[1] According to Kermode and Mayo’s Film Review, BBC Radio Five Live, 15th September 2017. Hello to Jason Isaacs.

You may also like:

Sundar Vadlamudi reviews Masks of Conquest: Literary Study and British Rule in India by Gauri Viswanathan

Indrani Chatterjee on monasteries and memory in Northeast India

Isabel Huacuja reviews The Forgotten Armies: The Fall of British Asia, 1941-1945 by Christopher Bayley and Tim Harper

Joe and his nephew Steve are searching for another Chan, their friend Chan Hung, who seems to have disappeared with $4,000 of their cash. Along the way, they encounter a gallery of Chinatown personalities and settings, revealing aspects of the district that are rarely visible to visiting tourists. They venture past the bustling restaurants and the pagoda roofs and dragon-embellished streetlights of Grant Avenue into the tight quarters of greasy commercial kitchens; the packed fish markets and grocery stores of Stockton Street; narrow, laundry-festooned residential alleyways; a local senior citizens center; and the Neighborhood Language Center offering English classes for new arrivals.

Joe and his nephew Steve are searching for another Chan, their friend Chan Hung, who seems to have disappeared with $4,000 of their cash. Along the way, they encounter a gallery of Chinatown personalities and settings, revealing aspects of the district that are rarely visible to visiting tourists. They venture past the bustling restaurants and the pagoda roofs and dragon-embellished streetlights of Grant Avenue into the tight quarters of greasy commercial kitchens; the packed fish markets and grocery stores of Stockton Street; narrow, laundry-festooned residential alleyways; a local senior citizens center; and the Neighborhood Language Center offering English classes for new arrivals.

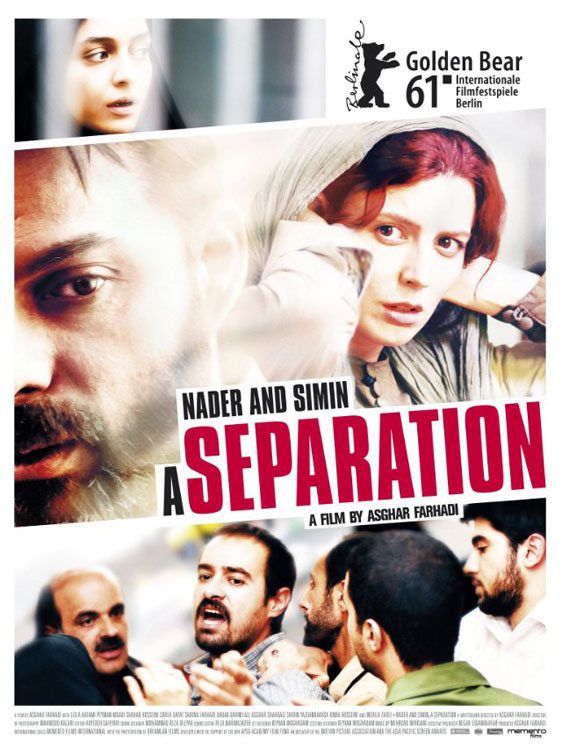

As is indicated by the title, the film focuses on the separation of Nader and Simin, an affluent couple residing in Tehran. Simin wishes to escape Iran’s repressive society and move to Canada, which she believes is a more suitable environment to raise their daughter, Termeh. Nader refuses to leave under the pretext that he must stay in Iran to take care of his elderly father who is suffering from advanced Alzheimer’s disease. Their situation is further complicated by Razieh, a devout Muslim woman from the lower economic class, who is hired to help care for Nader’s father. Numerous financial and personal conflicts pit the well-off Nader and Simin against Razieh and her unemployed, debt-ridden husband, Hojat.

As is indicated by the title, the film focuses on the separation of Nader and Simin, an affluent couple residing in Tehran. Simin wishes to escape Iran’s repressive society and move to Canada, which she believes is a more suitable environment to raise their daughter, Termeh. Nader refuses to leave under the pretext that he must stay in Iran to take care of his elderly father who is suffering from advanced Alzheimer’s disease. Their situation is further complicated by Razieh, a devout Muslim woman from the lower economic class, who is hired to help care for Nader’s father. Numerous financial and personal conflicts pit the well-off Nader and Simin against Razieh and her unemployed, debt-ridden husband, Hojat.

Guatemala. Denese and her adopted family travel to Guatemala, where she discovers she is Dominga Sic Ruiz, a survivor from a 1982 Guatemalan massacre in which both her parents were murdered by the Guatemalan military. The documentary recounts how Denese rediscovers her own identity as Dominga—an Achí Maya woman, and the horrendous political context that led to her being put up for adoption in the United States.

Guatemala. Denese and her adopted family travel to Guatemala, where she discovers she is Dominga Sic Ruiz, a survivor from a 1982 Guatemalan massacre in which both her parents were murdered by the Guatemalan military. The documentary recounts how Denese rediscovers her own identity as Dominga—an Achí Maya woman, and the horrendous political context that led to her being put up for adoption in the United States. by

by

By

By

By

By

A few years ago, after discussing the origins and consequences of the

A few years ago, after discussing the origins and consequences of the